Teaching with Contemporary Art

Deconstructing Soft Power

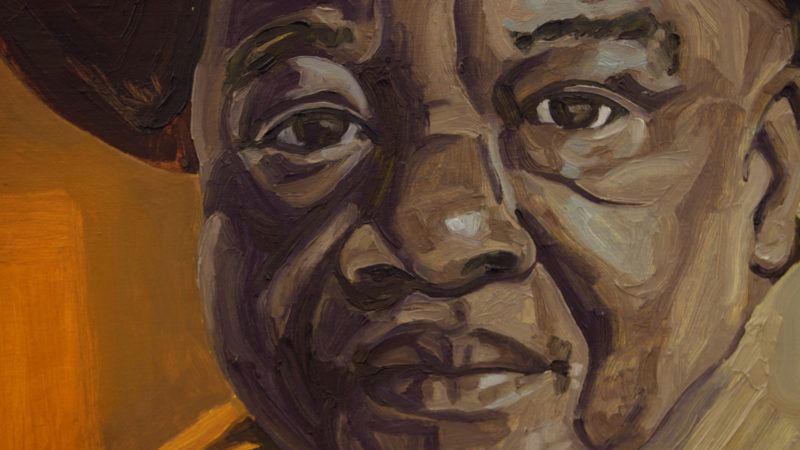

Jordan Casteel. Harold, detail, 2017. Oil on canvas; 78 × 60 inches. Production still from the Art21 New York Close Up film, Jordan Casteel Stays in the Moment.

The experience of seeing art in person cannot be replicated. Institutions like museums can deeply affect visitors, offering them rich reflections of history and culture, and thus museums can serve as dynamic teaching tools. Yet, due to the original nature of many museums, these institutions can also enable a singular perspective, of White privilege, which is reinforced through the denial of its existence. Because of this potential for social impact, we must acknowledge the soft power that museums hold. Soft power, as defined by the American political scientist Joseph Nye, is non-coercive.1 It acts as an invisible, manipulative force of influence, and it gains momentum when it goes unacknowledged. This same sentiment is reflected in the definition of the constructs of Whiteness and White privilege.2 As a museum educator, at the Denver Art Museum, I believe we have the responsibility both to recognize how museums can exhibit soft power as well as to create educational programs that challenge and can deconstruct that soft power.

Brian Jungen. Cetology, 2002. Plastic chairs; 64 × 496 × 66 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver. © Brian Jungen.

Museums in the United States are beginning to adhere to an idea of new modernism, which is no longer exclusively White, European, and male.3 Many museums are working toward gender, racial, geographic, and socio-economic inclusivity, as represented by shows like Jordan Casteel: Returning the Gaze, Jeffrey Gibson: Like a Hammer, and Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Place. Works by contemporary artists like these—and by Art21 artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Fred Wilson, John Feodorov, Brian Jungen, and Pedro Reyes—lend themselves to critical thinking and discussions of relevant social issues. These special exhibitions can be powerful, but they often exist as isolated, temporary displays among many permanent ones within one museum. If we do not create a structure to question the rest of the museum, we default to a Eurocentric way of seeing, understanding, and valuing. If we cannot acknowledge the soft power at work in our cultural institutions, we are empowering it.

In my role, reimagining what school experiences can be like at the Denver Art Museum, I explore how the practices of contemporary artists can inform the way we look at all art. What are contemporary ways of seeing? How can we help students to recognize soft power at work? What tools can we provide them to explore or challenge the contexts surrounding the artworks and the soft power of the museum? What tools are needed to help students identify a singular perspective? In order to dismantle the soft power at play, visitors must be able to recognize, acknowledge, and name it. It is important to teach this skill in our classrooms, to cultivate critical citizens.

Pedro Reyes in his home, Mexico City, 2015. Production still from the Art21 Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 8 episode, “Mexico City,” 2016. © Art21, Inc. 2016.

While we educators are experimenting with this approach in practice, I am working to develop activities that encourage students to create new meanings of art by investigating the contexts and spheres of influence surrounding works of art and by applying experiences from their lives. My intention is that these activities will create a framework for students to develop new habits and modes of inquiry while offering participation with institutions, in taking advantage of art’s ability to reframe ways of seeing. We tested our first iteration of such socially focused school experiences with participating teachers. We presented the thesis of the exhibition, Natural Forces: Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington, along with a number of reproductions of artworks from the show. We used an adapted version of the visible-thinking routine developed by Project Zero, the Claim Support Question. Working in small groups, the teachers formulated arguments for and against the claim that these works of art represented the quintessential American spirit. To support or refute the claim with contextual evidence, teachers were provided primary sources from the time period, a variety of media such as newspaper clippings, folk songs, poetry, photographs, and videos. The supporting evidence was intentionally collected from multiple perspectives, including those from people whose voices might not be represented in the artwork. In this way, teachers were able to view the show with a critical eye and to construct their own narratives and meanings. This modification of the thinking routine enabled viewers to question the soft power that an exhibition or museum may not be acknowledging.

John Feodorov. Office Deity, 1995. Oil on canvas and wood panel; 84 × 56 inches. City of Seattle Portable Works Collection. Photo: Spike Mafford. Courtesy of City of Seattle Portable Works Collection.

The protocol described above could be used in any museum and any classroom to teach students to challenge how things appear. How can teachers use this in their classrooms? When selecting a work of art or an exhibition for discussion, first ask: what is the unspoken message? Ask: which perspectives are being shared, which ones are not being shared, and what contextual influences have made this work of art important? Then, collect supporting documents that reveal a broader view of the possibly complex factors behind the creation of a work of art and its reception.

I hope that other educators will see value in using this method to deconstruct the soft power of institutions with their students—and in working toward dismantling this power. When we give students the time and space to thoughtfully support or refute a claim and come to their own conclusions, we empower the next generation of critical thinkers.

1 Joseph S. Nye, “Soft power,”” Foreign Policy 80 (1990): 153–71.

2 S. Ahmed, “A Phenomenology of Whiteness,” Feminist Theory 8, no. 2 (January 2007): 149–68.

Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism (London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books, 2019).

3 Hakan Topal, “Reimagining Museum Design, With Education at the Forefront,” Hyperallergic, December 19, 2019.