Teaching with Contemporary Art

Creating Communities of Care in the Early Childhood Art University Classroom

Production still from the Extended Play film, “Crafting Lineage: Tanya Aguiñiga.” © Art21, Inc. 2021.

How do we create the kind of caring communities that make our lives better, happier, and even in some cases, possible? What kind of infrastructures are necessary to create communities that care?

As a Los Angeles educator working with high school visual art students and university art education students, I’ve been experimenting with ways to incorporate the practices of activism, interaction, and interdependence towards social justice into my classrooms, trying to make smaller, more tight-knit communities in a city that can feel large and isolating.

My post-pandemic students in high school and university are struggling with mental health, socialization, and classroom behaviors that can be alienating. I want to provide strategies for students to come together to identify and address issues that matter in our localized communities, using Art21 as a framework to examine how artists can bring communities together, even for short periods of time, to reconnect. I’m inspired by the ideas in the Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence by The Care Collective. It resonantly speaks of our need to develop a practice of care to create more caring (or like-minded) communities. The Collective shares that “we need localized environments where we can flourish: in which we can support each other and generate networks of belonging.”

University students taking the course “Art in Early Childhood” consider what issues exist in their communities and how they can be addressed through art. The class is mostly comprised of adults working in preschools, after school child-care centers, as elementary classroom assistants, or those planning to work as elementary teachers or social workers. Few students who enroll in the course are artists, which creates a need to frame the conversation to expand our beliefs on what art is and what art can be. This is especially true if there is a lack of confidence among the students in their ability to teach children how to be artists. When considering this work, we define the concepts of art as installation (temporary and site specific) and intervention (requiring participants to make the work function) and ask these questions:

- How can artists engage in community actions for social, political, and environmental change?

- Why is interaction a critical portion of an artist’s practice?

- How does interaction lead to action?

- What is ARTIVISM?

- Can schools be spaces of change?

As future educators and social workers, I want students to create a collaborative art intervention. This intervention can include site specific and temporary work based on an issue they share a mutual passion for with other classmates. The work must be done in teams and should be something scalable to have young children as participants. This aspect creates an interesting dynamic in the planning of the work because the work has to be achievable given the myriad scheduling constraints the typical working university student faces.

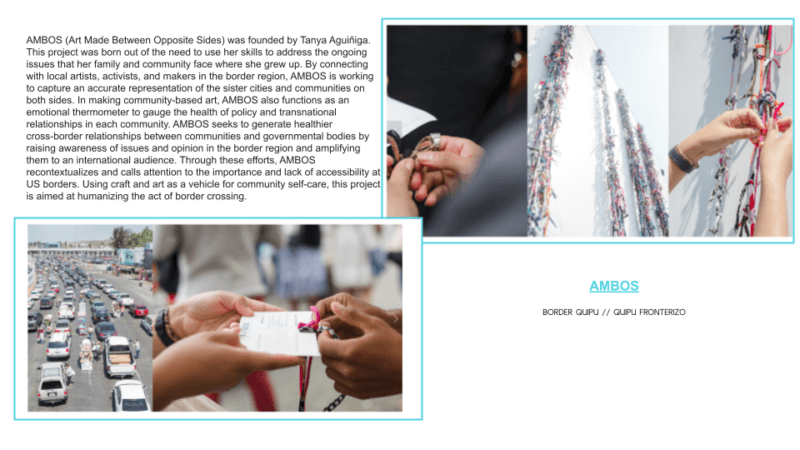

Slide from Art 383 Lecture.

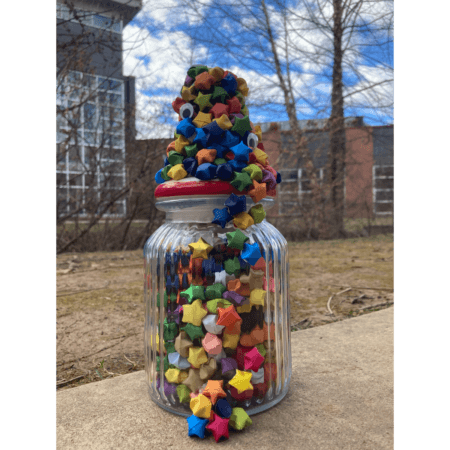

We examine Tanya Aguiñiga’s collaborative project, AMBOS, as a strategy for engaging communities across nations. She has a talent for weaving together stories that are carried out by many volunteers through small collaborative acts, and in turn impact the lives of many. This approach is something we can learn from. My students find her work particularly poignant, as it speaks to many of their lived experiences in entering the United States or in trying to connect with family across the border. Her segment in the Art in the Twenty-First Century episode, “Borderlands,” is emotionally charged; she demonstrates how art connects people, and how small actions like the braiding of the Quipo are a visual representation of connections across barriers. This work helps visualize how personal experiences can be translated into work that leads to social change. Small actions lead to bigger changes. This is something students see and can apply to the spaces that they work in.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty First Century Season 7 episode, Legacy. © Art21, Inc. 2014.

We also examine Tania Brugera’s segment from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 7 episode, “Legacy,” looking at how she uses educational spaces and institutions to educate, create discomfort, and connect immigrant communities. Students appreciate the power that Brugera’s podium represents to speak their minds and ask the question of whether a concert with children is considered an artwork or a performance. Students comment on Brugera’s work in critical discomfort, and express that they weren’t sure before watching this video if the work she’s doing is considered art, especially considering the craft-based projects students create in their elementary programs. Brugera’s work expands their ideas about what art can be and what role an artist can take in engaging educational spaces for art-making.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty First Century Season 7 episode, Legacy. © Art21, Inc. 2014.

After viewing and discussing the works, we use “he resource “The Process Deck” by The Black School. The Black”School website explains that “The Black School: Process Cards exists as an interactive tool to be used as a learning tool in a workshop environment to demonstrate our methodology for designing creative activism projects. Download the P”oject Outline worksheet here.” This card deck serves as a prompt to help students identify community issues that concern them. They brainstorm and then diagram possible responses through action-oriented artworks. Some common examples of issues students often engage in are mental health, joy, autism awareness, the need for humor, and self-love.

Process Deck by The Black School and Art 383 students interacting with the deck and handout. Courtesy of Jess Perry-Martin.

Brugera and Aguiñiga create models for working in collaborative communities using art to connect and bring about change. In the same way, my students join together to overlap with the issues they care about and the strategies they want to utilize to address those issues. Strategies take time to develop and implement. My students have only a few weeks to research, plan, and implement their artistic interventions and, consequently, not all projects are successful. Trial and error and sharing of ideas before implementation lead to greater outcomes. Students create a proposal in class and present them to each other, seeking feedback and guidance from their peers on everything from locations for installation, time of day to maximize participants, permits for on-campus events, expected participants, engaging a reluctant public, and documenting interactions, especially with children.

Courtesy of Jess Perry-Martin.

Through feedback, dialogue, and collaborative art-making, we are creating tiny communities of care, working as artists to build a world, even for a few hours, that is better in the way we believe it needs to be.

How will we know if our work is contributing towards building communities of care?

Courtesy of Jess Perry-Martin.

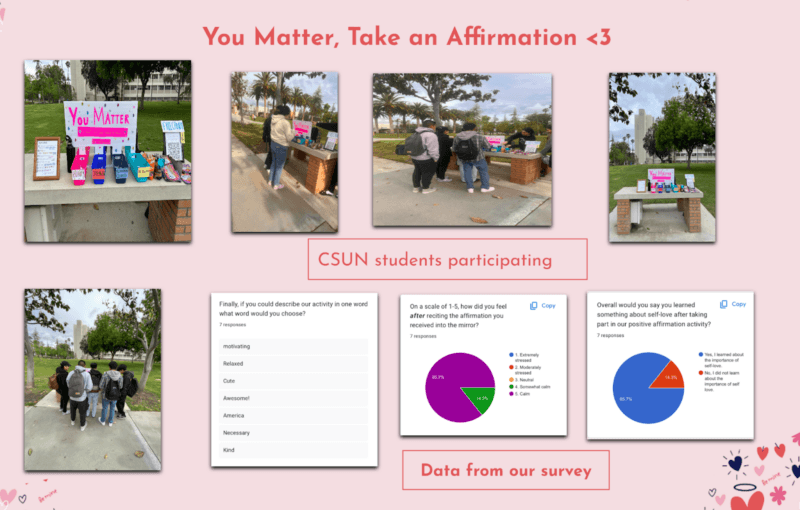

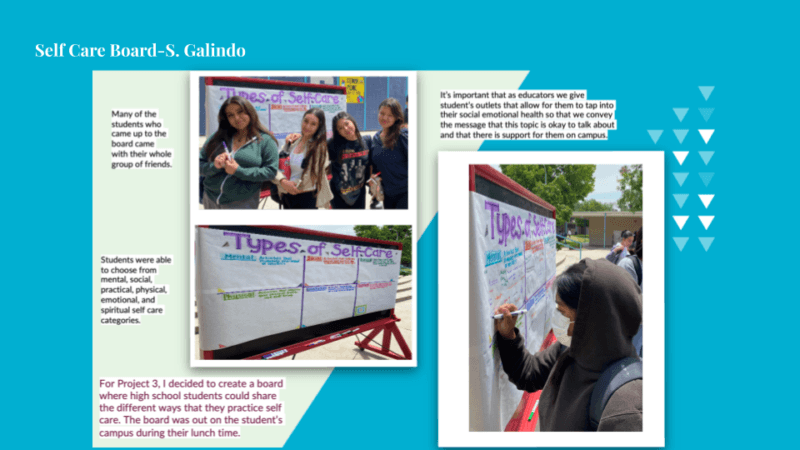

Students collected data on the value of their interactions (see example above) and shared their reflections in a”final paper. Leah B. shared, “I think we worked best on working with other students on campus and creating tha” safe space to”be vulnerable.” Stef shared, “as a School Climate Advocate, I am always trying to think of new and creative ways to build positive relationships with students while also supporting students in their social and emotional growth. This activity allowed for students to share their ideas with one another and maybe even lea”n of other self-care methods.” The projects led to some unexpected outcomes. As students set up their interventions in public spaces on the university campus, The Oasis (campus mental health center) invited groups to collaborate in future events to support wellness. The early impact of Aguiñiga and Brugera continues to demonstrate how art can engage communities at all levels. Their example has paved the way to create spaces for this ongoing and important work in the university and elementary classrooms.

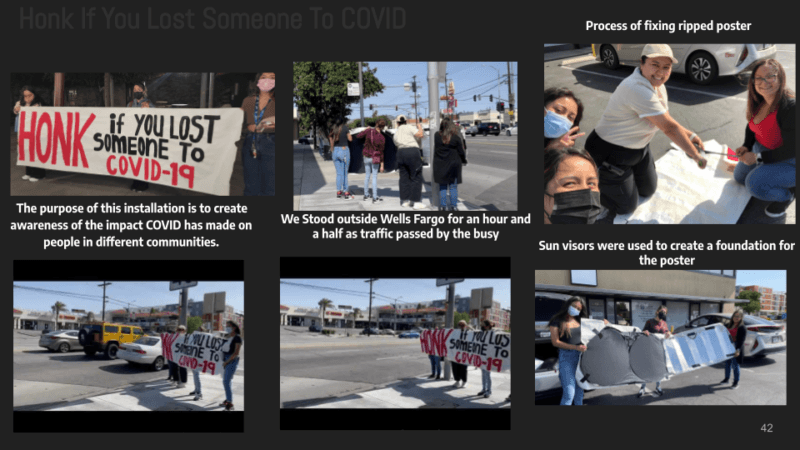

Student slides sharing their collaborative art-based actions that engage communities in high schools, colleges, and the community around the university:

Courtesy of Jess Perry-Martin.

Courtesy of Jess Perry-Martin.

Courtesy of Jess Perry-Martin.

References

- Aguilar, E. & Cohen, L. (2022) The pd book: 7 habits that transform professional development. Jossey-Bass A Wiley Brand.

- Dawson, K., & Kelin, D. (2014). The Reflexive Teaching Artist. Intellect.

- Graham, D. (2023). ED&I and SEL Across the Country: National, State, and Local Perspectives. [webinar panel]. Connected Arts Network Summer Institute.

- Sawyer, I. & Ramirez Stukey, M., 2019, Professional Learning Redefined An Evidence-Based Guide

- Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2006). Understanding by Design (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall