Teaching with Contemporary Art

Crafting Conversation

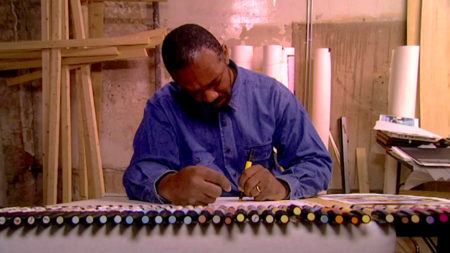

Courtesy of Birra-Li Ward.

How can we help our students develop the ability to hold genuine, face-to-face conversations? In a world dominated by digital and increasingly shortened communication methods and quick exchanges, teaching students the art of conversation has never been more essential for empowering them to be able to connect, listen, understand, and foster empathy.

Imagine you are standing in the classroom, mid-conversation with a student. Yet there is a second student next to you saying your name on repeat and appearing blissfully unaware that they are interrupting. I will make perhaps a safe assumption: that all educators have had students who interrupt. In fact, it may be a daily occurrence. In my observations, watching students converse with each other, I am noticing that there is an increasing need to help students learn how to converse; it seems to be becoming a lost art.

Many students are growing up more comfortable texting in shorts and acronyms than talking, leaving them possibly unprepared for the nuanced dynamics of ‘communication’ within society. It has made me curious about the opportunities that I could be providing students in the Visual Arts classroom to explicitly practice ‘conversation.’ Teaching students how to have a meaningful conversation isn’t just about social etiquette, it’s about training for future performances that are mostly unrehearsed.

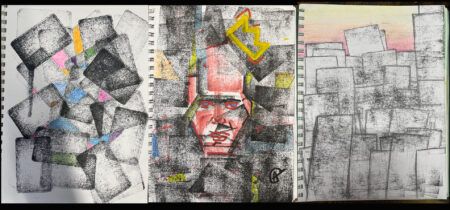

Production still form the Extended Play film, “Rose B. Simpson: ‘Dream House.'” © Art21, 2024.

At the Summer Institute earlier in the year, Art21 Educators were privileged to meet and hear from Andrea Chung, the director of the Extended Play “Rose B. Simpson: Dream House.” Chung’s shadow is briefly seen in the episode; it’s one of the rarer moments that we are reminded of the production teams’ presence. Although we don’t often see or hear them, they are pivotal in being the conduit between the audience and the artist. Artists like Rose B. Simpson share profound and moving insights about their practice through the guidance of the team. The level of depth that the conversation reaches allows us as the audience to feel intimacy and empathy; it feels tender and real. This episode and the gentle provocation of Chung’s shadow led the Year 7 students in my class to wonder and explore the questions of “How did this conversation transpire? How was rapport and trust built to elicit such profound moments?”

To do this they needed to consider what occurs before, during, and after the interview.

How can we peel back the veil and learn more about how the conversation might have been crafted with Simpson? Taking post-production out of our minds, the students and I watched, paused, rewatched, and hypothesized, and came up with a series of questions that may have been asked. Such as, “Tell me about the influences on your installation? How much of yourself do you put into your artwork? Can you explain the significance of the materials like fabric and clay in your art making? How does your connection to ancestral lands inform your ideas? How would you like your audience to experience your art?”

The students workshopped the delivery of the questions and how they may change or be adjusted to accommodate the various people we might be conversing with, using one of Grice’s theories. We considered colloquialisms and when they might be beneficial.

Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Jordan Casteel Stays in the Moment” © Art21, Inc. 2017.

There is yet another layer to this exploration of meaningful conversation. In the New York Close Up episode “Jordan Casteel Stays in the Moment,” Casteel eloquently says, “There is a certain amount of mindfulness that it requires, to slow down enough, to really feel what it is to be present with someone in a moment.” Casteel discusses the time spent in the studio going back to the first moments of feelings and re-engaging with the subjects in the paintings and the initial interactions and immediate conversations had. The segment shows Casteel building rapport by answering questions to those who the future subjects in a painting will be; the connection has already begun. The warmth, openness, and the ability to converse is fundamental to the subjects being themselves and being represented by Casteel in this way.

How do we build trust through sharing yet maintaining balance in a conversation? The students undertook a series of interviews with each other under altering time constraints and discussing random topics. They noted how challenging it was to refrain from interjecting and actively listen; this then led to them trying to generate a responding question based on what they heard. The struggle was real, and it was evident that we needed more practice in creating depth in conversation.

Anh Do is an Australian artist, comedian, and author. I felt that it would be beneficial for the students to learn conversation from his work. The students watched parts of Anh’s interview with Adam Goodes (a famous Aboriginal ex-football player) while he simultaneously painted Goodes in “Anh Do’s Brush with Fame.” In class we considered how Anh provided and gave space for the conversation to take the path it needed to take. The students noticed Anh’s use of paraphrasing and open-ended questions, and then considered what effect these had on the conversation. In discussions, the students noted the length of pauses and the way in which Anh stops and pivots his attention between Goodes and to the painting at key moments and why he does so.

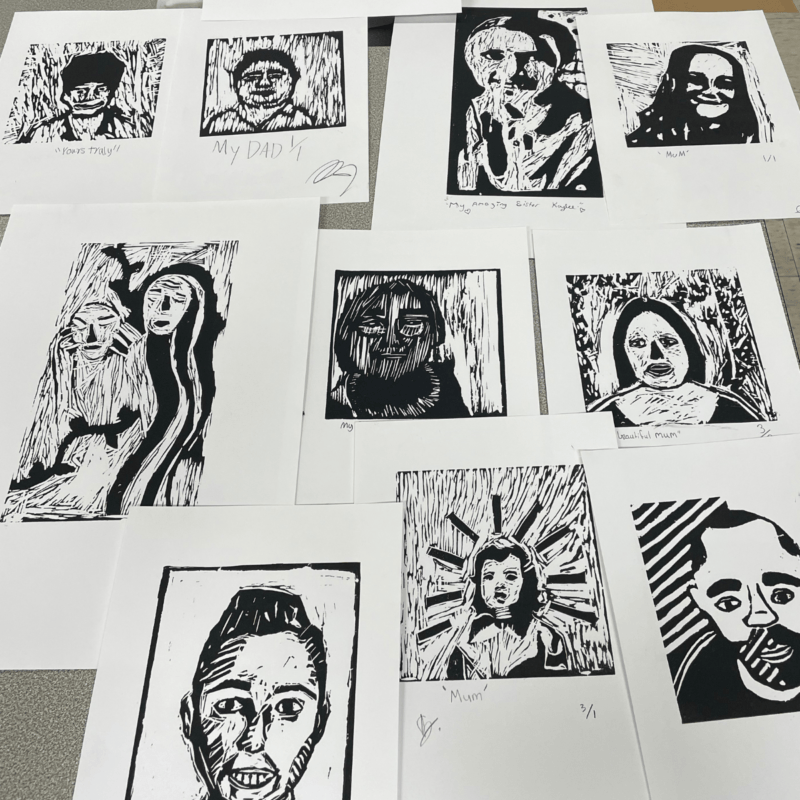

Courtesy of Birra-Li Ward.

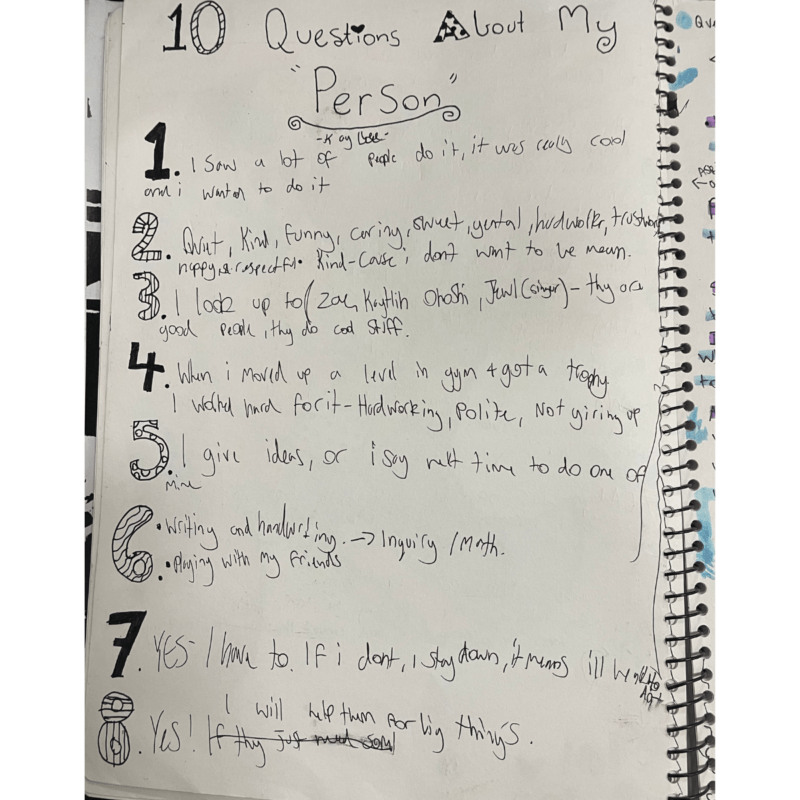

The students began mind-mapping who they might consider an important or influential person in their life and with whom they could have a conversation. They completed some research about this person and wrote questions they would ask, contemplating what counter questions might then be asked. After more practice in conversation, the students, armed with these recently practiced tools, interviewed their chosen person.

I felt a sense of relief when the students returned after the weekend with warming stories, such as how their parents met, why a dance teacher began teaching, or how a student had not realized the struggle of their parents arriving in Australia. There was also one student who even documented an interview with themselves. Portraits of these people were then created and produced with care. The depth of the conversations had influenced what the students wanted to communicate in the meaning of their artwork.

A conversation between two people is like collaborating on an artwork; it is a craft. By empowering students with these tools, we can help them navigate relationships, resolve conflicts, and engage in thoughtful dialogue that goes beyond surface-level exchanges. Teaching students the art of meaningful conversation has never been more essential, or more rewarding.