Teaching with Contemporary Art

Contemporary Art and Third Culture Kids

Student artwork by Minjeong Kwon. Photo by Emily Relf.

The moment I received the email inviting me to join Art21 Educators, I was in Beirut, Lebanon, completely exhausted. My family had a nightmarish previous night in an Airbnb unit that we discovered, far too late, was completely infested with bedbugs. There, in the low evening light after a lovely Lebanese meal, these little monsters were invisible, until they emerged at 2:00 a.m.; I showered them off my son while my husband sought new accommodation. Within a few hours, sitting in a pristinely clean hotel room, everything had shifted: I was thrilled to be part of the Art21 community of educators, and we ran off to explore Beirut with our Lebanese friends, making GoPro videos of Roman ruins and staring out at the Mediterranean Sea.

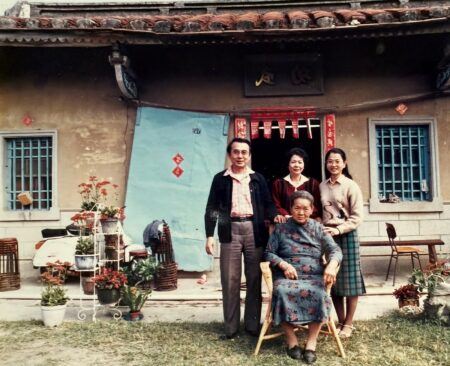

Travel anecdotes like this are typical for my family, as my husband and I have worked as international teachers for the bulk of our careers. The beauty of the expat-teacher lifestyle is that international travel is an expected part of your life, to the point that not traveling feels abnormal. Living as a long-term guest in a foreign country is the greatest advantage that comes with being a certified teacher. My love for art came with my passport visas for Bangladesh, Jamaica, Thailand, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia, my latest home.

At the American International School, Riyadh (AISR), teaching children of more than 62 nationalities means catering to a very special type of person: the third-culture kid. These globetrotters have spent a significant part of their developmental years living in one or more countries outside their passport country. They often move from one country to another due to their parents’ diplomatic, military, or missionary vocations. My son, for example, is American, born in Bahrain and raised mostly in Saudi Arabia, but he is not Arab and only spent summer holidays in the United States. Third-culture kids are more likely to quickly adapt to change, acquire cultural intelligence, and develop nuanced interpersonal skills due to living in a multicultural environment. Formed from the conceptual amalgamation of the terms home culture and host culture is a unique and personal third culture¹. My son at age five perfectly expressed this concept with his reply when was asked where he was from: “Saudi America.”

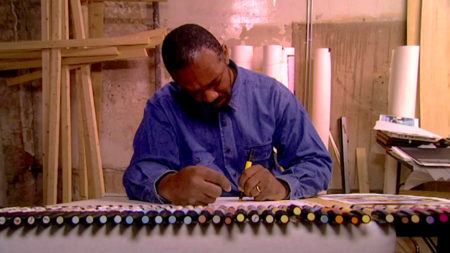

Watching the little artists in grades three to five in my classroom, I marveled at how they, as global learners, easily accepted different points of view. This is why AISR was the perfect laboratory for teaching with the works and words of contemporary artists. Since contemporary art is not bound by a specific canon, material, method, style, or nationality, my students embraced with unbound enthusiasm everything I shared with them. Contemporary art can make learning magical for kids, and I saw that it was even more so for our special population of students. Yinka Shonibare CBE and Shahzia Sikander are perfect examples of artists who explore how cultures can not only clash but also harmonize and who have developed their artistic vocabularies outside their home countries. But one of our favorite discussions was about Trenton Doyle Hancock’s major work, The Former and the Ladder or Ascension and a Cinchin’, which stimulated more conversation than any piece I’ve shown to a grade four class. After watching the Extended Play film, the students dove into a guided discussion about why the figure in the piece doesn’t have a head, what the meaning of the pencil is, and how the background looked exactly like the wire fence of the heavily fortified exterior of their school. They compared Hancock’s planning sketch to the final piece and discussed why the image of a pencil replaced that of a gun. Questions arose: “Why is he trapped?” “What gives us a feeling of power?” “What is freedom?” “How can he get out of this tough situation?” These are relevant issues for any child making sense of their place in the world, and the conversation could have gone on, far longer than I planned!

Trenton Doyle Hancock. “The Former and the Ladder or Ascension and a Cinchin’,” 2012. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas; 84 × 132 1/8 × 2 1/2 in. (213.36 × 335.6 × 6.35 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Sydney and Francis Lewis Endowment Fund and Pamela K. and William A. Royall Jr., Fund for 21st Century Art with funds contributed by Mary and Don Shockey Jr., and Marion Boulton Stroud. © Trenton Doyle Hancock.

The beautiful challenge with third-culture kids is supporting them in developing a sense of personal identity. Their families will share certain values with them, and their host country will impart perhaps a different set of values, but their school is one place where these values may need to coexist. These students often lack a feeling of belonging to a specific shared identity. One important approach that I use in the classroom is to provide many opportunities for each student to develop personal identity, offering every chance to answer the questions, “Who am I in the world?” and “What do I value?” This includes giving them the freedom to explore personal themes or stories and interpret materials and methods without constraints.

Photo by Emily Relf.

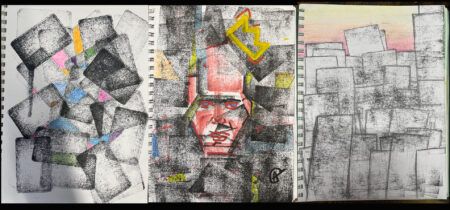

I love how my grade four students used Trenton Doyle Hancock’s work as a starting point to brainstorm their ideas and then figured out how to translate these into collages. While freely generating ideas in sketches, students could formulate a theme and commit to it before pulling out the scissors. Their only guideline was to make everything out of paper and include a background, large shapes, and small details. From this exercise, no identical pictures resulted; each one was as unique as the many personalities in my classroom. We used paper collected over the course of the year from repurposed projects, and we treated paper to recreate some of Hancock’s studio process. A piece created by a student named Sara featured a rich man who was sad regardless of his wealth and a poor girl in rags who was happy and smiling. This clearly was a strong statement about how Sara measured happiness. She showed her personal values by crafting tiny faces, figures, and an environment to resonate with the viewer.

Student artwork by Sara Alrajih. Photo by Emily Relf.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my family found ourselves in a predicament, feeling a little trapped or confused, like Hancock’s headless figure stuck in a ladder. Like many expat families, we had to unexpectedly relocate from our Saudi home back to the United States. I am forever thankful for my community of Art21 Educators for their presence and compassion during this difficult transition; to me, being in my home culture of the USA feels more foreign than living in the center of the Muslim world. My son is the resilient one among us, with little understanding of the larger impact this move had on our lives. But during his most vulnerable times, he tells us he wants to go home, meaning Riyadh and the Saudi life he knew. For third-culture kids, the concept of home is challenging because it might not be the same as the home country. My own third-culture kid now needs a teacher to validate his experience, understand him, and ask him to share his stories. I encourage all teachers to seek out their third-culture kids: ask them what they value, where they are from, where their parents are from, and how they define their version of home.

Photo by Emily Relf.

¹Ruth E. Van Reken, David C. Pollock, and Michael V. Pollock, Third Culture Kids: The Experience of Growing Up Among Worlds (3rd ed.), Nicholas Brealey, 2010.