Deep Focus

Biography is Complicated

The abstract sculpture that Judith Scott crafted over the course of her fifteen-year career in the studios of Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, are composed of found materials encased and interwoven, in yarn and other fibers, most commonly. Unlike the work of other artists at Creative Growth (such as William Scott), the work that Judith Scott made does not invite a conversation about the artist’s biography. When exhibited, the works are intriguing yet hermetic. This is in part because Scott intended an audience of one: – herself. Her visually and tangibly rich constructions, even those in which found objects are clearly visible, do not invite narrative or metaphorical readings. But, because Scott was an artist with developmental disabilities, the standard critical discourse has tended to prioritize a fascination with the story of the maker over a formal interest in the objects themselves.

The artist complicates curatorial decisions in fascinating ways.

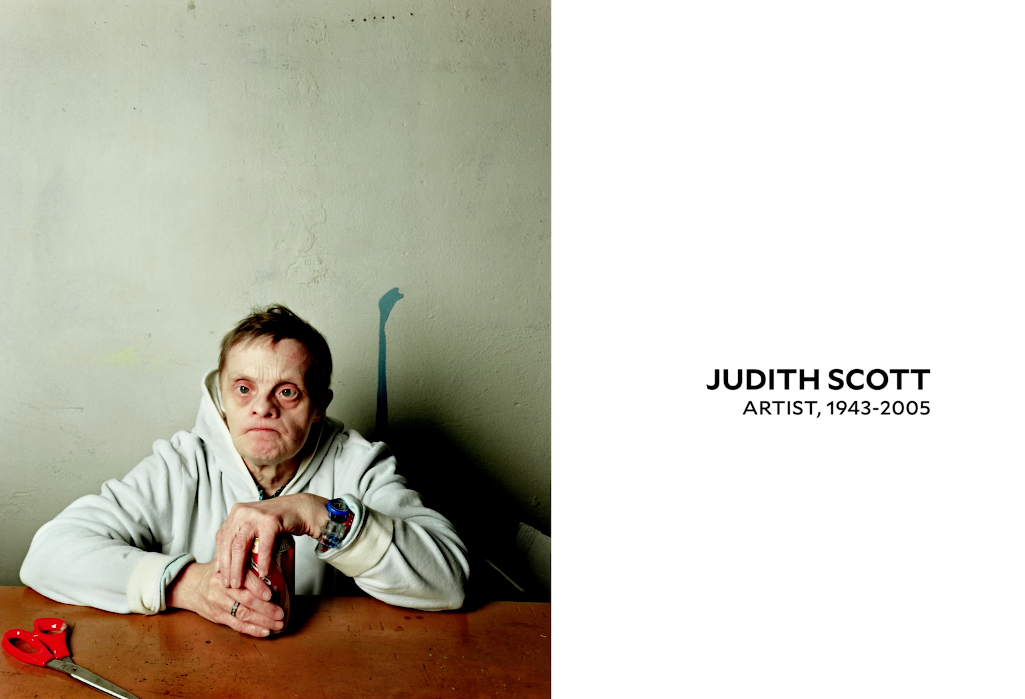

Unlike most artists, Scott had Down syndrome, was deaf and largely mute, and was institutionalized for more than thirty-five years before becoming an artist.But she was also unusual in that she was solely interested in the making of her objects: the activity of gathering her raw materials and the intensive and lengthy development of each enigmatic sculpture. Many people who were lucky enough to witness her creative process describe her working at the same table in the studio at Creative Growth, focusing on a single piece at a time, sometimes for weeks or months, before pushing a work away with a resolute gesture of completion.The life of the things she produced, once she was done with them, did not engage her. Nor was she interested in the reception of her work by the larger world. She did not revisit or express interest in works she had finished, but if she saw one exhibited at the gallery at Creative Growth, she was known to offer it an affectionate wave or pat of acknowledgment.

The yarns and other materials she favored came to Creative Growth from various sources, and her selection of these items reflected not only the pragmatism of using what was on offer but also clear preferences for particular colors, combinations of hues, and favored textures. Scott had teachers who guided her early creative development, and while her material choices were informed by those interactions, her work emerged from a purely internal dialogue.

The yarns and other materials she favored came to Creative Growth from various sources, and her selection of these items reflected not only the pragmatism of using what was on offer but also clear preferences for particular colors, combinations of hues, and favored textures. Scott had teachers who guided her early creative development, and while her material choices were informed by those interactions, her work emerged from a purely internal dialogue.

As noted, Scott typically incorporated found objects into her sculptures. They are often visible in the final work; —a table fan, a crutch, and a shopping cart were hard even for Scott to disguise. Other items including keys, a pilfered paycheck, an electric coil from a stove are completely submerged within the works. However, her attraction to, or the significance of, the things she scavenged and salvaged remains hard for a viewer to parse without falling into a quicksand of pop psychological speculation.

Scott did not title or sign her works. She left no notes, sketches, or recorded ideas revealing the thinking behind her making. She gave no interviews. She never noted favorite pieces, nor did she single out any with particular significance, such as a work, that might represent a breakthrough in her creative process. She didn’t acknowledge the influence of artists or of art history. The artist’s unknown and unknowable intentions complicate curatorial decisions in fascinating ways. While photographs that document Scott working in the studio confirm her single-minded devotion to her craft and her sense of humor, they offer few clues for the presentation of her work; in many cases, not even an orientation for placing them on a pedestal is known for sure. While curators regularly make aesthetic decisions about installing works of art, such choices can quickly seem arbitrary and even heavy-handed in the case of an artist who resolutely did not care about such matters.

This curatorial hand-wringing over seemingly simple display decisions occurs because one of the most significant challenges in presenting the work of an artist whose voice was sharply circumscribed by her life experience is to avoid adding complicating layers of interpretation that can calcify into a narrative fable. The inclination to prioritize biography is not uncommon when one looks at work by artists with disabilities. The history of outsider, visionary, or art brut artists—three largely interchangeable terms by which artists with disabilities have been inadequately categorized—has emphasized the dramatic life narratives of these artists. When it comes to the art of Judith Scott, the vacuum of uncertainty concerning the intention of the artist is readily filled with her story, which fosters projections and metaphorical readings that easily detract from what she created.

Judith Scott is specifically contemporary and particularly urgent

The push to bridge art-historical silos and to position outsider artists within the mainstream often requires shifting the one’s focus away from artists’ biographies in order to contextualize their creative contributions. Another timely approach to curatorial thinking prioritizes the acknowledgment and description of difference as a means to expand and enrich the canon. Recognizing Scott’s life experiences while guarding against a reductive reading of her work places Scott squarely within the current dialogue of identity politics in the field of contemporary art. Feminist artists, artists of color, queer and LGBT artists, and all any artists who in some way choose to incorporate or address issues of personal identity in their work, have participated in changing the art-historical landscape in recent decades. Scott’s work is a complex case study in considering the implications of these methodologies.

The 1970s feminist adage, “the personal is political,” aptly summarizes the urgent desire of artists and activists, in the face of a dominant and monolithic formalism, to acknowledge the intersections between life, art, and the political structures that all people live within. With this lens, one’s lived experience is a necessary component of art rather than a reductive limitation that reduces it, as has so often been the case of artists with disabilities. The fact that Scott’s work is so readily situated within current conversations about abstraction, biography, and social politics makes the point—if it needed to be made at all—that Judith Scott’s complex artistic voice is specifically contemporary and particularly urgent.