Interview conducted for Art21 in May of 2024 by Jurrell Lewis. Original photography for Art21 by Harry Mitchell. All other photography courtesy the artist, Anat Ebgi Gallery, and Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

Big Question

How do we complicate the relationship between power and violence?

Gray Wielebinski lets things be strange.

Interview by Jurrell Lewis

I think of my practice as a form of collage. I’m collaging materials, mediums, and ways of making with ideas. It might feel like I don’t have a signature medium per se, however there are recurring themes and interests that often run throughout my work, like the relationship between power and violence and how they can be potentially uprooted, confused, or made lateral by something like desire.

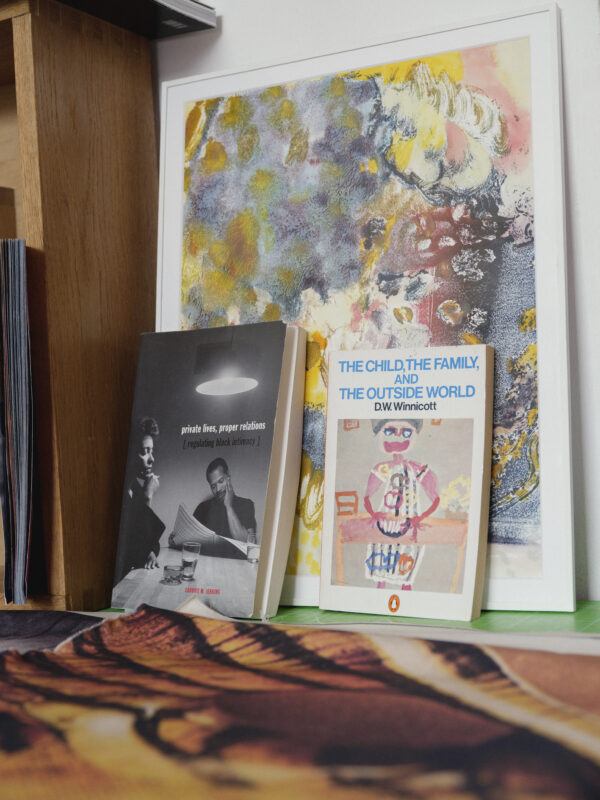

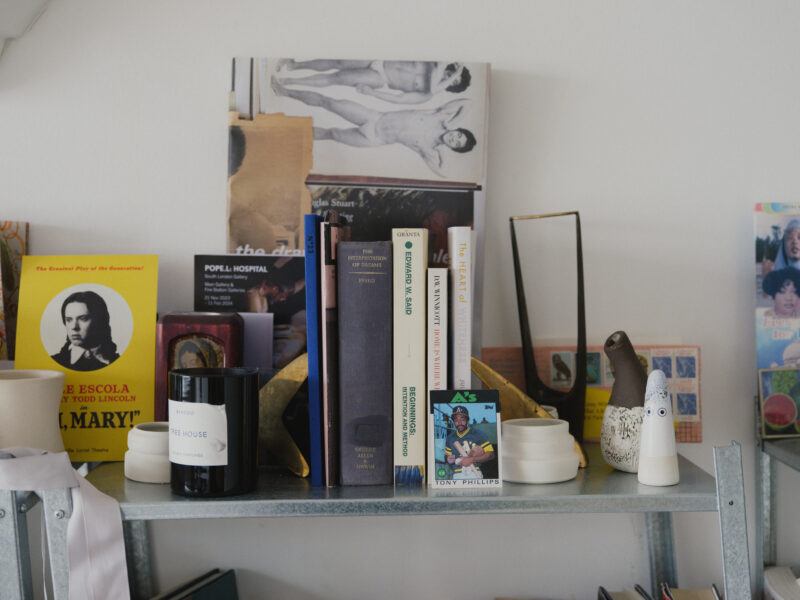

Working on the ICA London show, “The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low,” I wanted to represent the idea of worlds within worlds but move away from utopia/dystopia all while approaching it with more ambivalence. For a number of years, I have been making work about the binaries between private and public, intimacy and surveillance. Drawing on the ICA’s location on the Mall, I focused on the historical contexts of the Cold War, bunkerism, and nuclear apocalypticism, as well as the informational drives of science fiction, intelligence gathering, and social scientific research. The result was a strongly site-specific and architectural show. It had a science fictional and sometimes cartoonish aesthetic with these references to queer history throughout. I’m interested in the different relationships you might have to those things.

The show’s title is taken from an essay by Samuel R. Delany about the language of science fiction. He explains that it’s not necessarily the content but the sequencing of the language that transports the reader to another world. For the ICA show, I wanted to explore that idea on a grand scale, while also bringing the idea of worldbuilding down to earth: thinking about how we are all making our own worlds and how and when they bump up against one another. What is the end of a world, and what’s “The Apocalypse,” vs. what types of apocalypses have already occurred and to whom.

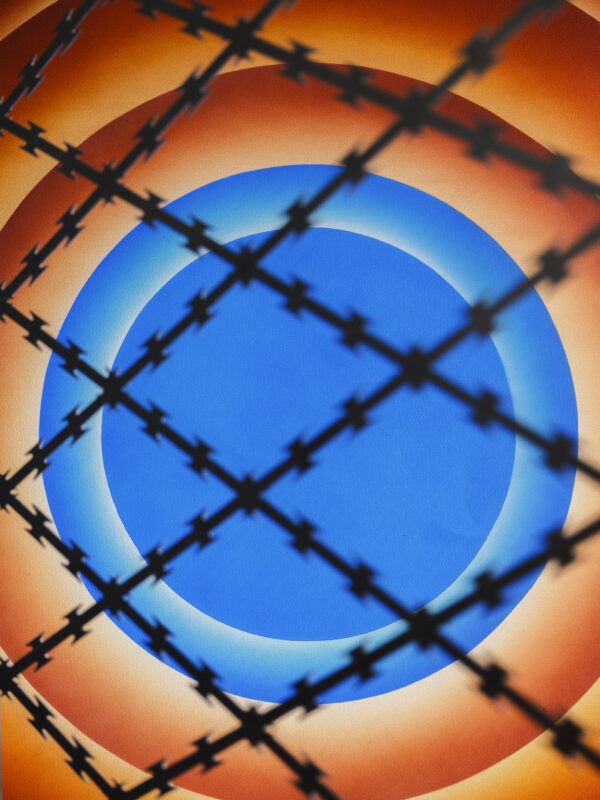

Within the exhibition, there is a peephole referencing a pillbox embrasure. In making this I was inspired by the ICA’s proximity to The Citadel, a war bunker camouflaged by ivy. I’m interested in how these violent mechanisms of control, whether it’s literal weaponry or architecture that’s created for violence, produce an intentional design sense that underlies the human within the inhumane. If you’re a soldier, the pillbox embrasure is designed to have your gun be outside and if someone’s shooting at you, you’re a lot harder to hit because there’s just a little slit and the bullet will ricochet off of the pillbox. However, it also has the motif of mise en abyme, of concentric rectangles: it becomes a frame within a frame, a world within a world. It’s interesting to consider this tension and what happens when we recognize how designed the world around us is, particularly things designed to appear “natural” or inevitable and to consider what happens when violence is abstracted in plain sight.

In the exhibition, the main gallery was brightly lit and included various works and architectural interventions: from a large basketball scoreboard mysteriously counting down and keeping score to a frieze of sunsets taken from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “Querelle,” to a red velvet and concrete circular conversation pit and whitewashed windows. In contrast, I turned what is normally the “Reading Room” annex space into a sort of bunker, separated from the main room by a perpetually-open steel razor wire ornate door.

The pillbox embrasure visible from the main room as a sci-fi like architectural flourish, is built into the wall in such a way that it physically imposes and shrinks the already limited space of the dark bunker room. The bunker has a lower ceiling and was dark and quiet, the walls covered with soundproof panels and lockboxes that are ubiquitous on city streets used for subletters or Airbnbers. I kept the lockboxes ajar and wired them with blue LED lights so they functioned as lanterns, the only light source inside the bunker other than the light from the doorway and the small slit of the embrasure that allowed you to look out onto the exhibition (and anyone inside of it in secret). While you do have the “control” or “power” of being able to watch people from this peephole without them knowing, I also wanted to consider at the same time: at what cost? What are the bargains you’re making when your priority is power or control?

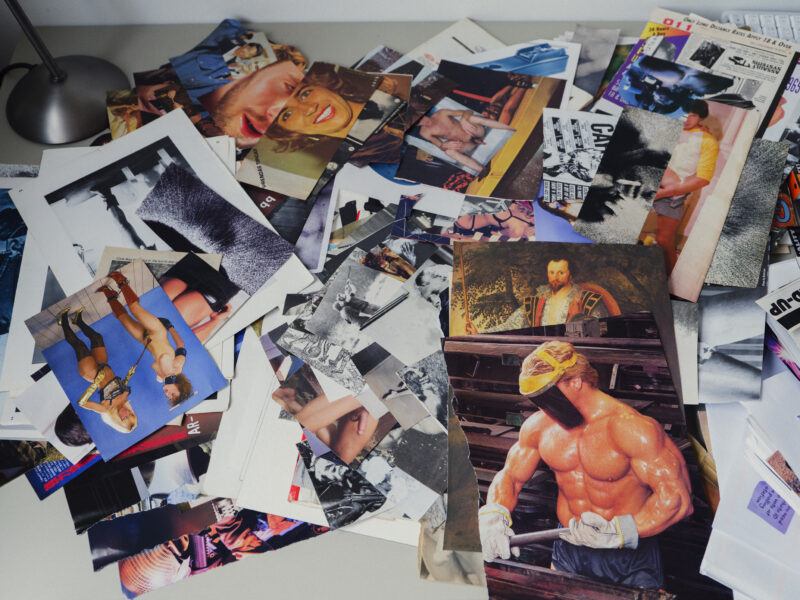

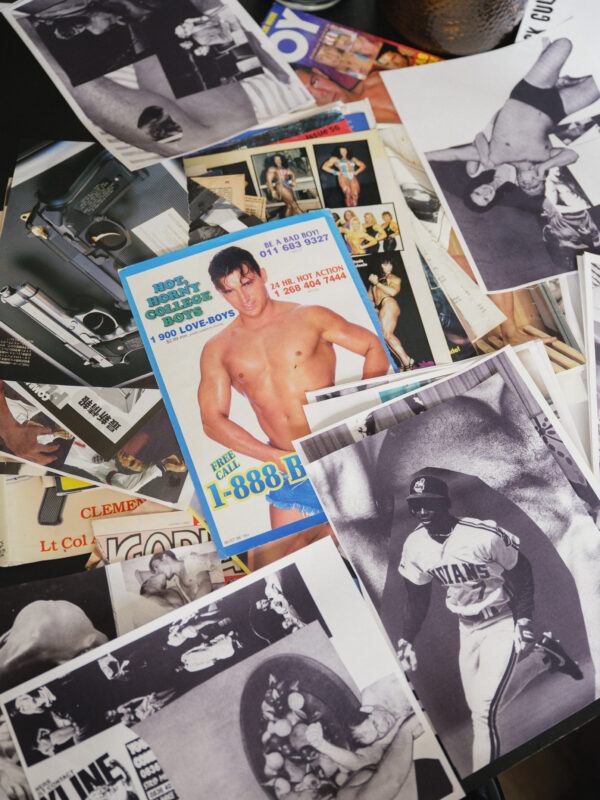

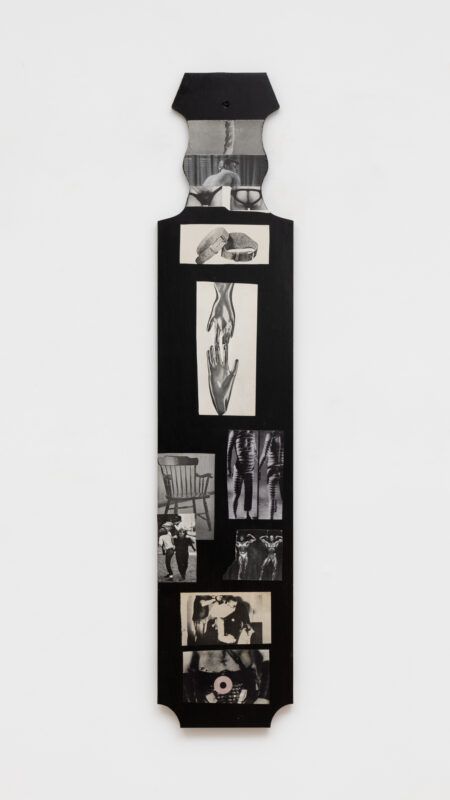

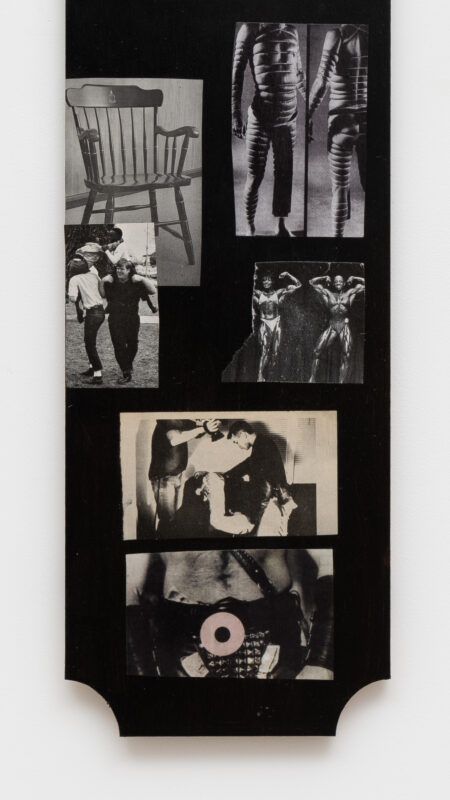

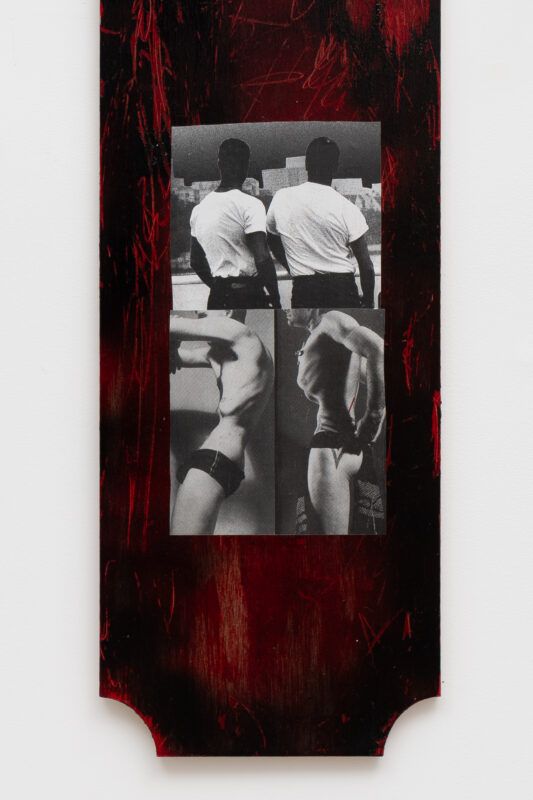

My 2023 Exhibition at Anat Ebgi, “Fratricide,” was based around collaged fraternity paddles. I was thinking about sex, violence, ritual, and play, in the context of fraternities, the family, and the military: institutions that are vital to the normative American self-image but which are built on brutality and coercion. The things I’m interested in with regard to the paddles and these homosocial spaces are these relationships between power and desire, violence and eroticism. I’m using this as an entry point to look more closely at how power functions and to see how it could be made strange: where assumptions might be uprooted, or the seemingly concrete might unravel.

The paddles are made of wood and all have the same silhouette. The imagery on them is taken from a variety of sources, some of which are pornographic. A lot of motifs that are important within my practice recur: rope, bullets, targets, dicks, muscles, appendages, restraints, siblings, and twins. By cutting these images up and taking them out of their original context, even and especially, the nonpornographic images start to seem sexual. A classic anti-porn argument is that porn is wrong because it cuts up people’s bodies and objectifies parts at the expense of the whole. It’s an anti-collage argument!

The idea of restraint is important and comes up in my practice in literal ways (images of men tied up taken from BDSM magazines) and in more figurative ways (cutouts from mainstream fashion and advertising, like 2000s Abercrombie & Fitch materials). In the latter, there is another kind of restraint or restriction of the body at play: these bodies represent a lack or exclusion, you realize what is missing in this narrow idea of “All-American” imagery (i.e, white, toned, young, seemingly affluent, and “collegiate”). There’s a darkness, a fraught heaviness in revisiting these nostalgic images, we like to believe we “know better” but they can still have the power to seduce us all over again, especially when looking through a homoerotic lens. There’s both pleasure and violence in these restrictive constructions of masculinity that I’m interested in, there’s a constant interplay going on—a dance or a wrestling match between signs, identities, domination and surrender, reality and fantasy. Collage can allow us to look at images differently, especially the ones we feel we may already know so well. Hopefully, there’s a bit of catharsis in those juxtapositions.

The bodybuilding subculture is also an area that I’m interested in and often revisit in my collages. There’s something about the extremity of the surface, the restriction, and the discipline involved in that process and lifestyle that compels me. The interplay of restriction and transformation plays with the idea of the surface and what’s underneath, the inner and outer self. There’s a question around pleasure, because bodybuilding involves such extremity of both form and practice: it deals with restriction as well as excess, it ramps up the consumption and objectification of the body through its extremity, and becomes a bit surreal. By laying bare and prioritizing the work, discipline, and lifestyle involved in literally “making” and transforming a body, there’s an ambiguity as to where the pleasure lies. Is it the pleasure of the bodybuilder or is it primarily designed for someone else’s pleasure, and who might that be and for whom it might be quite unpleasant altogether?

Some of the images I find to be most bizarre and beautiful, and can feel particularly erotic in the environment of the paddles, are from old fraternity yearbook magazines taken in very mundane contexts. Objects like chairs, close-ups of rope, and hands that look like they are in latex gloves reaching out to touch one another become more strange and complicated in the context of my work. I’m aware of and interested in the one-noted or “obviousness” of the pornographic images mixed into my work, but they are also being taken out of their immediate context of titillation. There’s something about them that’s strange, that you come back to and think about. I try not to overly complicate the connections, but to allow for room and to let that which is already quite complicated be complex rather than just a one-to-one juxtaposition.

I’m trying to maintain an ambivalence in my work and let my work be open, undone, and strange enough in a way that mimics how the world exists. It’s a process of letting things be more strange and complicated than we might expect, to remain curious and surprised. I’m also wrestling with and playing with expectations of myself and the audience. I think there’s something else that happens when I use the literal. The surface is already there, so you’re looking for something else.