Deep Focus

Analia Saban: Abject Inventions

Analia Saban. Folded Concrete (Gate Fold), 2017 Concrete on walnut pallet; 13 × 50 × 37 inches © Analia Saban. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers. Photo: Brian Forrest.

It could be said that, as an artist, Analia Saban is the opposite of an inventor. A keen student of art history, she plumbs its depths for tools, materials, and processes, finding ways to deconstruct and remake them such that they become remarkable art-historical statements. Canvases are unraveled to make sculptures, paint is turned into threads to weave canvases, and concrete sheets are folded in half like paper. A set of principles is turned upside down, reflecting a world onto itself while creating new principles and objects that are greater than or equal to the sum of their parts.

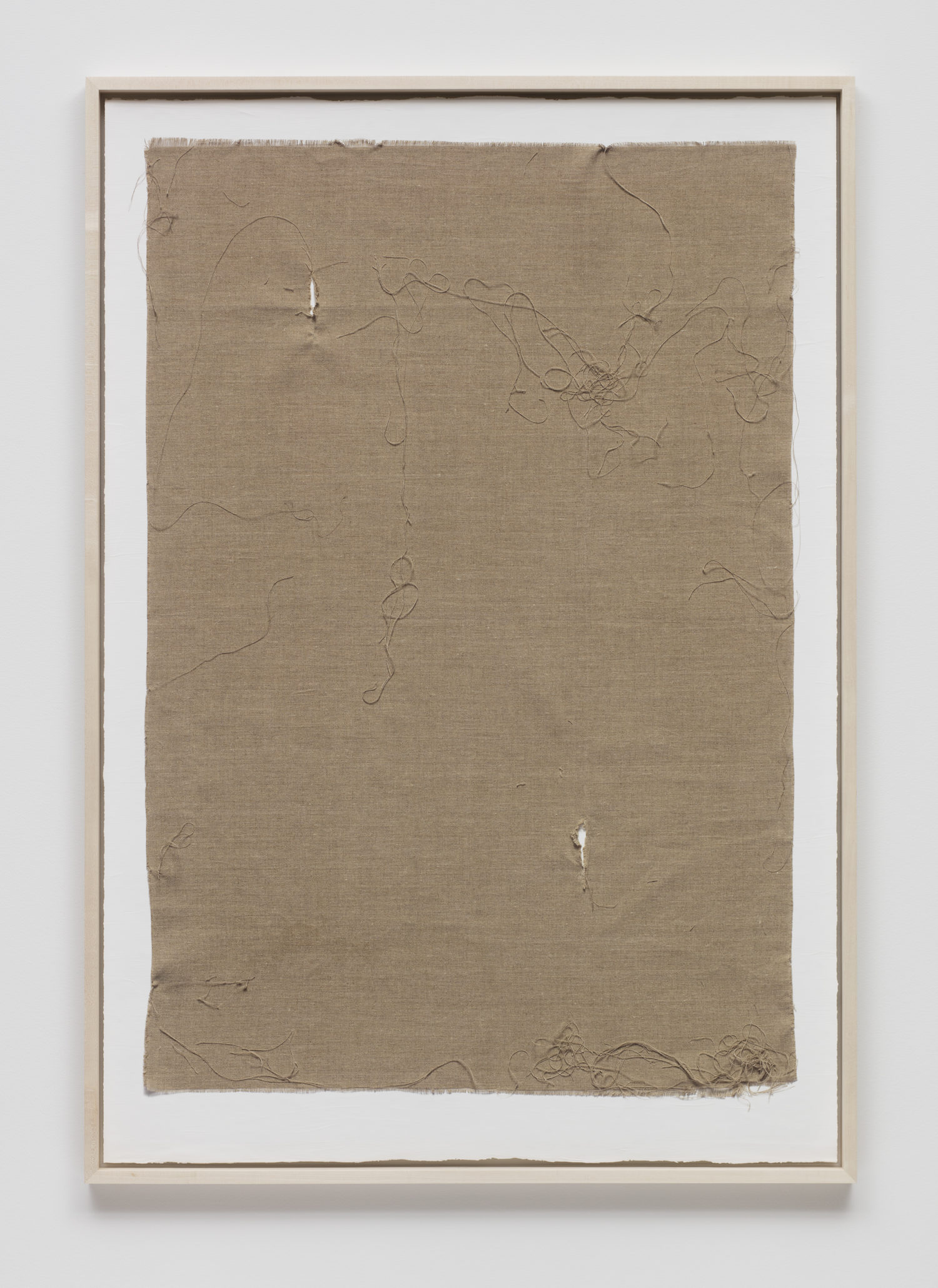

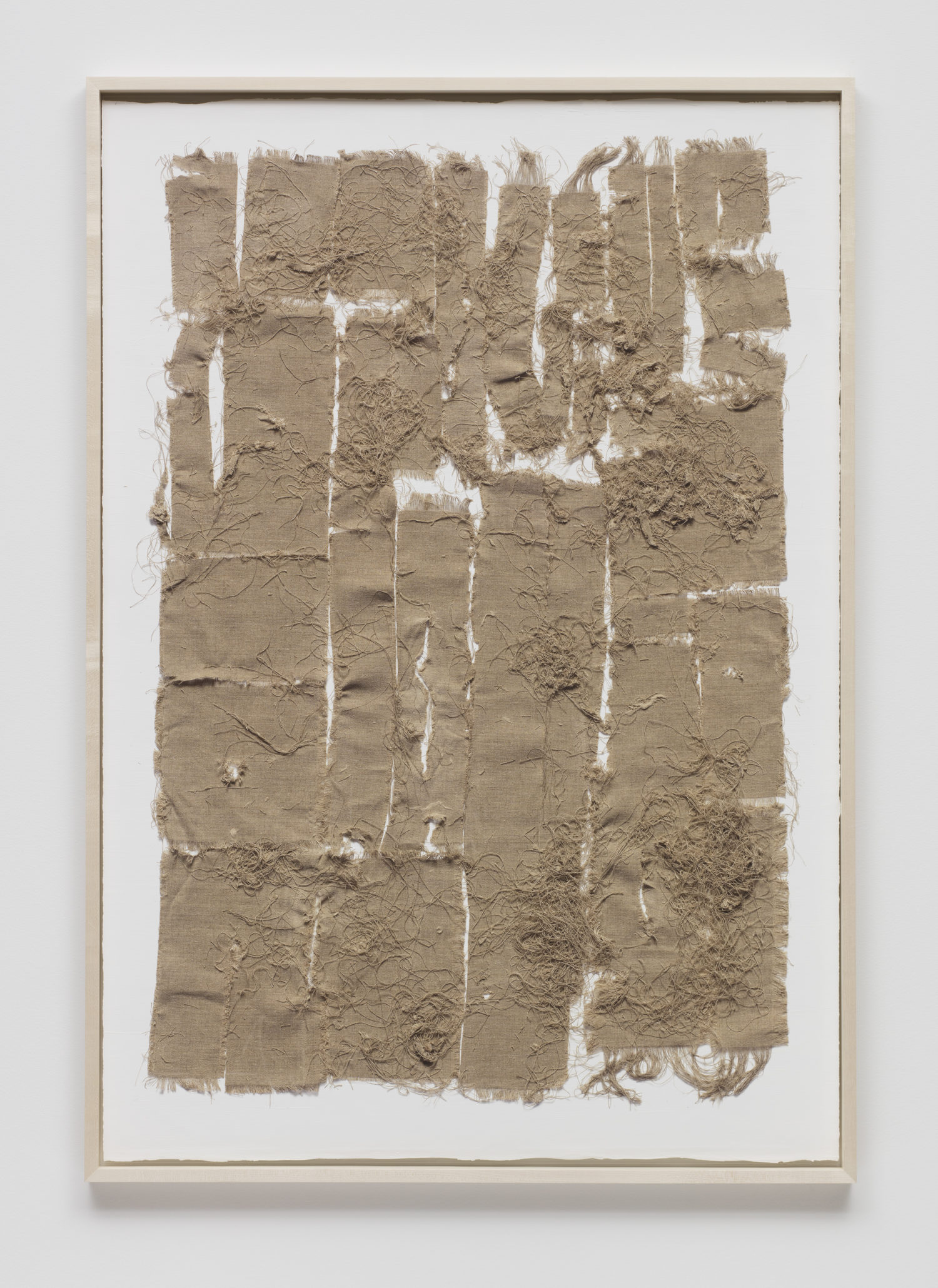

Many artists have engaged in this type of investigation, but Saban’s work is notable for being genuinely innovative in its processes and so deeply committed to its inquiry that the results are often no less than startling. For example, Threadbare (16 Steps) (2017) is a set of sixteen large-scale images of a gradually disintegrating linen canvas, from a brand-new bolt of cloth to a pile of linen threads, recently exhibited as part of the exhibition, Analia Saban: Folds and Faults, at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles.

Analia Saban. Threadbare (16 Steps), 2017. Pigmented ink print on acrylic paint; 60 1/2 × 41 3/4 inches. © Analia Saban. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers. Photo: Brian Forrest.

At first glance, the series appears to consist of actual linen cloths that have each been laid flat onto a large sheet of fine drawing paper and preserved inside a frame. Every detail of the cloth is so realistic that one can imagine reaching out and touching it, perhaps picking up the threads between one’s fingers. In a stunning reversal, however, it turns out that what looks like the paper is actually made of layers of white acrylic paint, onto which a photograph of the linen canvas has been inkjet-printed.

These are no ordinary high-resolution photographs; they were commissioned from a specialist photographer in Los Angeles who is known among artists for pioneering his own method of achieving hyper-realistic results. The photographer, using a mechanism that he built, slowly moves the camera over the object, photographing it as individual sections in a grid sequence. This labor-intensive technique, which took five hours per image to complete, creates a uniform depth of field across the entire plane of the object. The result is an image that more closely resembles the real object because it avoids the natural distortion that occurs with a single-perspective photograph. Thus, through an exacting manipulation, Saban has turned the medium into the canvas and the canvas into the subject and object.

Analia Saban. Threadbare (16 Steps), 2017. Pigmented ink print on acrylic paint; 60 1/2 × 41 3/4 inches. © Analia Saban. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers. Photo: Brian Forrest.

During a recent talk at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Saban mentioned that she had been greatly influenced by Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. She said the book was dark and depressing to read because of its relentless examination of essential human trauma—with analogies to being expelled from another body, like excrement—and the harrowing existential state that results. Saban also said, however, that “Once you go really deep [into the abject], then you can also appreciate the good parts: that you are incarnated and you do exist and you can breathe”—in other words, one emerges from the other side and can find the strength to reconstitute oneself.1 This description is akin to what Saban repeatedly achieves in her relentless artmaking process, which plunges into material disintegration before re-emerging with a new triumphant whole.

Analia Saban. Threadbare (16 Steps), 2017. Pigmented ink print on acrylic paint; 16 works: 60 1/2 × 41 3/4 inches each (unframed). © Analia Saban. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers. Photo: by Brian Forrest.

1. From the artist’s talk at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, August 13, 2017.