Deep Focus

African American Artists Reconstruct the Pastoral

William H. Johnson. Early Morning Work, ca. 1940. Oil on burlap; 38 1/2 × 45 5/8 in. (97.8 × 115.9 cm). Born: Florence, South Carolina 1901. Died: Central Islip, New York 1970. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

Art does not make appetites. It can manipulate and pervert human desire, but it cannot invent what is not innate. One of the best examples of this limitation is pastoral art. Pastoralism celebrates an idealized agrarian past; it communicates a desire for a simpler, less politically fraught society. The genre and the ideology that created it may seem uninteresting or even cliché, but what often goes unconsidered is the challenge that pastoralism presents to African American artists. For artists of color, American history offers few times and places that can be viewed as utopian. Responding to this absence unifies a group of artists whose work challenges both history and art viewers.

In 2012, the Smithsonian American Art Museum displayed one hundred works from its collection in an exhibition, African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era, and Beyond, curated by Virginia Mecklenburg. The featured artists addressed the rural African American experience, each with his or her singular take. William H. Johnson’s Early Morning Work (ca. 1940) and Sowing (ca. 1940) were the most genuinely pastoral images in the show. From Johnson’s images, a viewer infers the presence of poverty, but it is an idealized state.

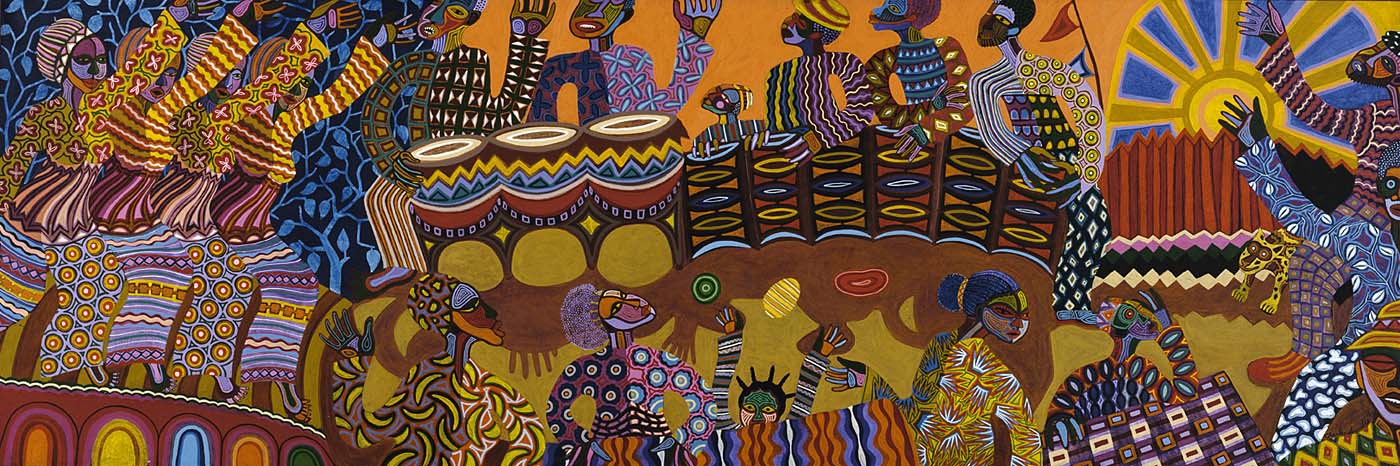

Charles Searles. Celebration, 1975. Acrylic on canvas; 27 1/2 × 81 3/4 in. (70.0 × 207.6 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Transfer from the General Services Administration, Art-in-Architecture Program.

Kara Walker. Installation view: Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2008. Photo: Joshua White Artwork. © Kara Walker. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

The pastoral elements of the exhibition changed tenor with Jacob Lawrence’s Bar and Grill (1941). Born in Atlantic City, Lawrence depicted in this painting his first experience of Jim Crow segregation: when visiting New Orleans, he had to stay in a segregated part of town and ride in the back of city buses, in which a bar split the passengers along racial lines. In the exhibition, Lawrence’s work marked a shift in attitude, from artwork that is sincerely pastoral to artwork that can only use the pastoral in a surreal or ironic manner.

Two artists, Norman Lewis and Charles Searles, created momentum within the African American community that resonates with many current artists. Lewis contributed the exhibition’s most caustic image, Evening Rendezvous (1962). With a swirl of red, white, and blue dashes on a grey background, the work appears to be a patriotic reinterpretation of Whistler’s Nocturnes—until the viewer realizes the white dashes are in fact hoods, and the image is of a Ku Klux Klan rally. An image that seemed saccharine turns mordant. Lewis’s handling of our brutal history initiated a political momentum that continues in many contemporary works.

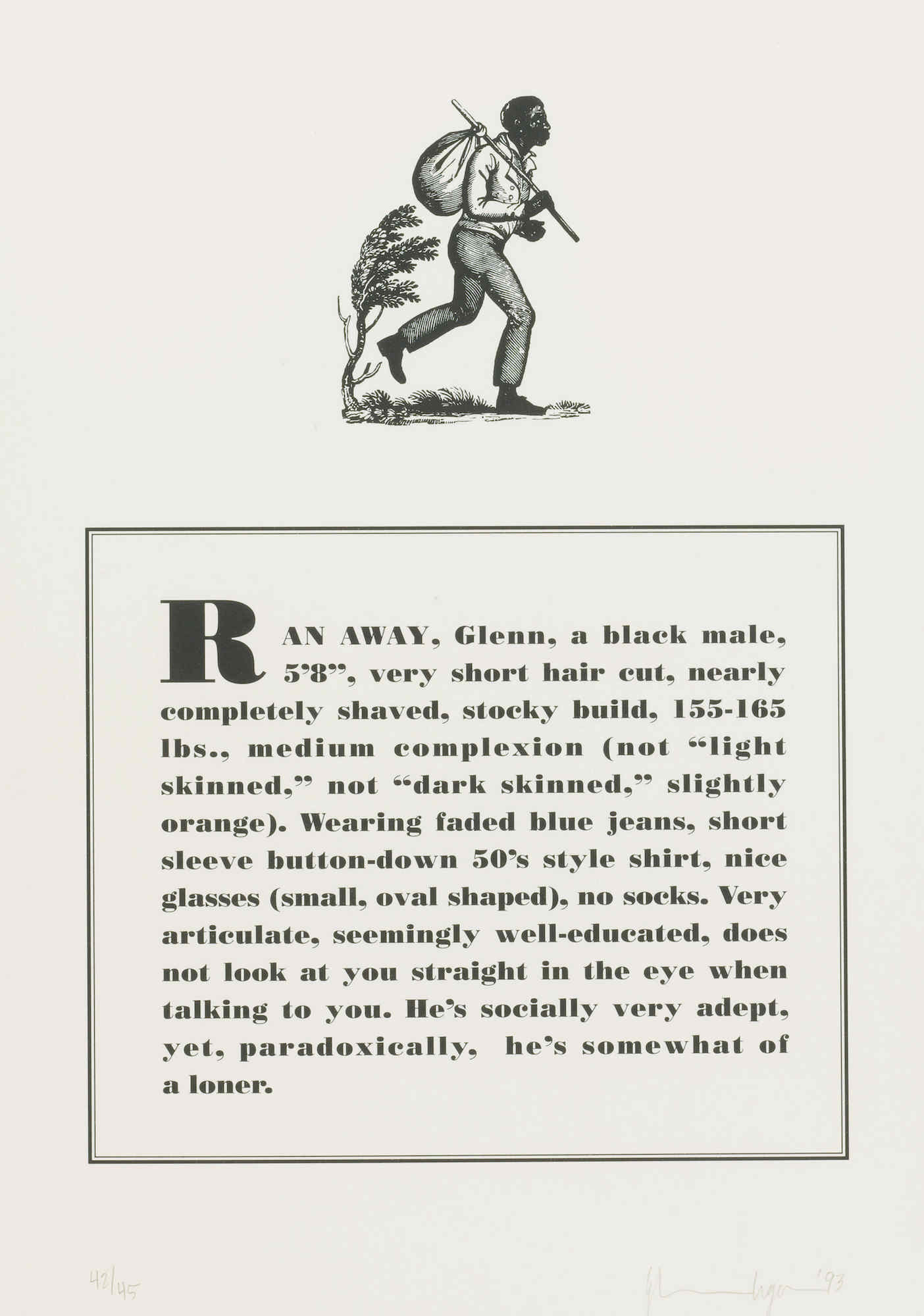

Glenn Ligon. Runaways, 1993. Courtesy of Thomas Dane Gallery.

Two African American artists, Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker, follow Lewis’s tack. In 1993, Ligon made a series of prints called Runaways; each featured a clip-art image of a black man with text describing Ligon as a runaway slave. Later, in a 2008 work, Untitled (Malcolm X), Ligon enlarged a coloring-book image of Malcolm X, complete with red lips and dimples. At his best, Ligon refuses the viewer any room to evade accountability for his heritage.

Kara Walker employed her cultural history to create nightmarish landscapes of sexual depravity and perversions in her 2007 traveling survey exhibition, Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love. The exhibition featured several panoramas composed of cut-paper silhouettes. The poses of the figures, dressed in antebellum outfits, allude to vile and violent sexual acts. Walker’s use of an antiquated process and pastoral images increase the shock value of the work.

Searles’s Celebration (1975) is one of the exhibition’s most fascinating pieces. The image depicts musicians and dancing figures in a composition that demonstrates horror vacui, in which the ground, air, figures, clothes, instruments, and drums all coalesce in a kaleidoscope of pattern. Rather than refer to a particular historical source in this work, Searles constructs a utopia of the imagination. This tactic links many African American artists across disciplines.

Nick Cave. Soundsuit, 2009. Mixed media including synthetic hair; 97 × 26 × 20 inches. © Nick Cave. Photo by James Prinz Photography. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Confronted by the beating of Rodney King, the artist Nick Cave created a series of Soundsuits. These elaborate, colorful, and flamboyant outfits became armor of the imagination. Theaster Gates created his own pastoral narrative through a multimedia project based on the invented story of Shoji and May Yamaguchi at their commune in Itawamba County, Mississippi—a tale of a Japanese master potter coming to the States and a Black civil-rights activist.

On September 24, 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened to the public. “[D]evoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life,” the museum both preserves works of great artists and emboldens current and future generations to not just record but also improve the African American experience.1

1. “About the Museum,” National Museum of African American History and Culture.