Deep Focus

Access to Healthcare: A Conversation Led by LaToya Ruby Frazier

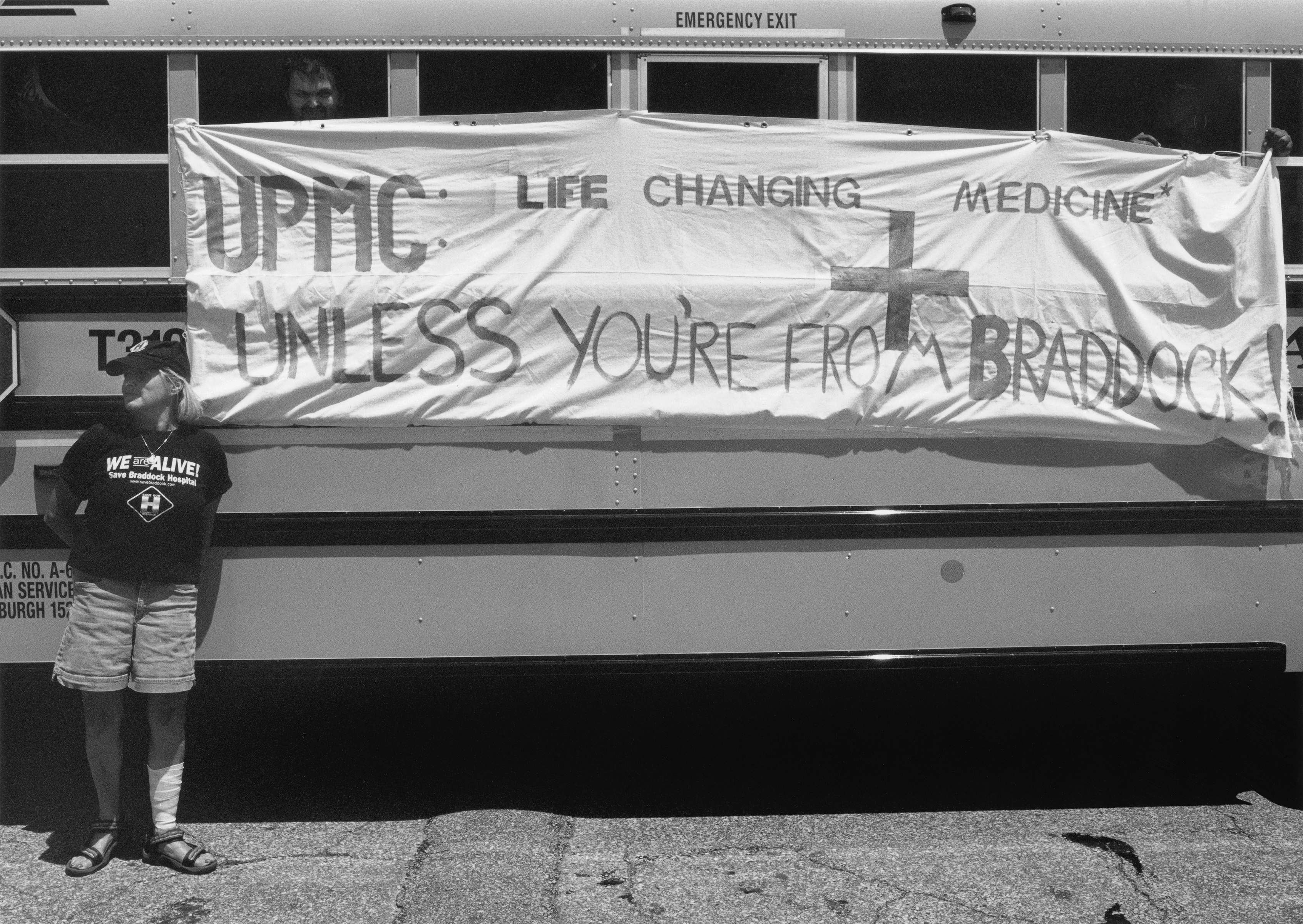

LaToya Ruby Frazier. UPMC Life-Changing Medicine, 2012. From the series The Notion of Family. Gelatin silver print; 20 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome.

On January 27, 2018, a public discussion took place at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, in Harlem, on the occasion of LaToya Ruby Frazier’s solo exhibition (on view January 14–February 25), her largest show in New York to date. The exhibition featured three distinct bodies of work: Flint is Family, The Notion of Family, and A Pilgrimage to Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Museum. After Frazier and her mother each experienced complications with her health, the artist developed relationships within the medical community and began seeing the implications of her work within the medical profession: to serve as a document of unequal access to healthcare. At the gallery, Frazier led a panel discussion with a scholar, a minister, and a doctor on the state of access and equity in healthcare, the history of artists and intellectuals who have fought for these rights in the past, and change-makers who are leading the charge today.

Participants

Gabriel N. Mendes holds a PhD in American civilization from Brown University and in 2015 published Under the Strain of Color: Harlem’s Lafargue Clinic and the Promise of an Antiracist Psychiatry. He is currently working on his second book, Through a Glass Darkly: Race and Madness in Modern America. Mendes is also currently the associate director of public health programs at the Bard Prison Initiative.

Reverend Kyndra Frazier is a licensed social worker and an ordained Baptist clergywoman, serving as an associate pastor of pastoral care and counseling at First Corinthian Baptist Church. She is also the executive director of the church’s free mental wellness and health clinic, the HOPE Center. Frazier is also an emerging filmmaker currently working on A Love Supreme: Black, Queer, and Christian in the South. An out, queer-identified woman, Frazier is using film to foster healing opportunities for the many thousands of people who have lost family and friends due to trauma inflicted by Christian fundamentalism.

Dr. Esa Davis is an associate professor of medicine and clinical and translational science at the University of Pittsburgh. At Presbyterian Montefiore Hospital, she directs a service that provides inpatient treatment to hospitalized tobacco users, offers education and training to physicians and clinical staff, and supports research through participation in clinical trials. Dr. Davis is also a board-certified practicing family physician with more than twenty years of clinical expertise, with a focus on women’s health. She is dedicated to improving access for underrepresented minorities and women in research and medicine.

Installation view of the exhibition LaToya Ruby Frazier at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York (January 14–February 25, 2017). Photo: Thomas Müller. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome.

Introductory statements

LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Notion of Family, the series title of the photographs that surround us, is a fourteen-year body of work. It began from a state of innocence; I was trying to visually represent the anxiety and depression I felt growing up impoverished in an industrial town within a post-industrial economy. The Notion of Family is about what it meant to come of age during the Reagan and the post-Reagan administrations: the union busting, the removal of social services, the war on drugs, police violence, dismantled communities, and interrupted educations. Meanwhile, the United States Steel Corporation was never held accountable for the toxic pollution it created. Some of the stories behind these images are the closing of our community hospital, leaving the elderly and people with terminal illnesses without access to emergency care or medical facilities, and the loss of drug and rehabilitation programs.

In 2014, I met Dr. Lisa Cooper, a doctor at John Hopkins who is Dr. Esa Davis’s mentor and friend. Dr. Cooper wanted to use my work, The Notion of Family, in clinical classes and with some of her colleagues because she saw the work as medical photography, a new conceptual framework to me.

A year ago, when my mother was on life support, her family physician was only a block away but refused to come to her aid. I was at my mother’s side, believing that she would live even though others thought it was impossible. Through Dr. Cooper, I reached Dr. Davis, who the next day started helping me to address the situation—she stepped in to help save my mother’s life.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. UPMC Professional Building Doctors’ Offices, 2011. From the series The Notion of Family. Gelatin silver print; 20 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

I believe that photographs are catalysts for change; they inspire hope and transformation. In the late 1940s, at the same time that the Lafargue Clinic was established, Gordon Parks and Ralph Ellison were collaborating on the body of work, Harlem is Nowhere. The purpose was to show what racism does to the psychology and the emotional stability of Black people in the United States, in Harlem in particular. Because these images were caught up in a bankruptcy lawsuit, they were never published in their full capacity.

What I find fascinating about this collaboration is what Ellison calls the “pictorial problem.” Ellison says in his notes to Parks, “To present photographic documentation of conditions that intensify mental disturbance, prints must be at once both document and symbol. …[The camera] must represent the negative sociological aspects of Harlem.” He continues, “… we shall try to begin with the maze of psychology, dispossession, and end with the maze, the clinic through which the individual is helped to rediscover himself, … in which he is given the courage to live in a hostile world. The point photographically is to disturb the reader through the same channel that he revives his visual information.” Ellison, who helped found the Lafargue Clinic, here creates a depiction of the psychology in Harlem.

Gabriel N. Mendes, PhD: We’re sitting just blocks away from where the walk-in Lafargue Clinic operated, from 1946 to 1958, in the basement of the parish house of St. Philips Episcopal Church on West 134th Street. Anybody with a quarter could come. The Lafargue Clinic was the first outpatient psychiatric clinic in a community of color in the United States. It never had major philanthropic or government funding, but it operated for twelve years on a shoestring budget. It was dedicated to what one co-founder, Fredric Wertham, called an experiment in the social basis of psychotherapy. It brought community members together: African-American intellectuals, writers, and artists of the mid-twentieth century, including Ralph Ellison and Gordon Parks. The clinic’s other co-founder was Richard Wright, author of Native Son and Black Boy, and many other works.

I’m a science historian interested in the intersection of race with the social, behavioral, and medical sciences. I’m most concerned with how everyday people encounter the knowledge that’s produced about them in everyday institutions. There’s a whole body of knowledge that’s crafted about difference, about identity—how do people actually live that knowledge? Particularly, I am interested in how people navigate and live the experience of normality and abnormality—or pathology—and how race is already inscribed in those two constructs.

The work that I did on the history of the Lafargue Clinic is in many ways just a footnote to the work of Frantz Fanon, published in Black Skin, White Masks. My interest in the clinic was sparked by Fanon’s work as well as my personal interest in the effects of displacement and dislocation. My mother is African-American; my father is of Ashkenazi Jewish origin, from Eastern Europe. My mother was an Army brat during the civil-rights movement in the 1960s. She was dislocated in many ways, always trying to find a place to be Black and to be herself in America, and she wrestled with a number of what would be called mental disorders.

I was hungry to understand the social foundations of these disorders. I was really interested in what radical intellectuals and doctors were doing to address the Great Migration of African-Americans to the North, what the psychiatrist Mindy Thompson Fullilove later coined as the “root shock” of dislocation, dispossession, and the vicissitudes that come at the psychological level. In many ways the Lafargue Clinic was an answer to addressing root shock.

Rev. Kyndra Frazier: First Corinthian Baptist Church has a membership of about ten to twelve thousand. The church is unique; it doesn’t feel Baptist. We encourage people to inquire, to ask questions, because often people in religious spaces are not taught to analyze what they are reading. We are very active in this community. Along with food programs and free events on creative arts, leadership development, and economic empowerment, we have the HOPE Center (HOPE stands for “Healing On Purpose and Evolving”), where we provide twelve free sessions—roughly three months—of counseling to individuals, couples, and families.

We call the people who come to our facility not “clients” but “innovators” because we believe that anybody who is intentional about their healing is the expert of their living experience. As one of the pastor clinicians, I help you to pull out the answers that are already inside of you.

The mental-health disorders that we see most often at the HOPE Center are anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. The Center’s location gives us the opportunity to break down the stigma about mental-health disorders. Because we’re connected to First Corinthian—a trusted institution in the community—people are more inclined to seek our services. It’s a challenge to serve everybody because we’re on a piecemeal budget funded by the parishioners. There are only five of us, and we were able to serve 358 people last year, which is not sustainable. We are working on a grant proposal, with the Department of Health and Columbia Medical School, to create a replicable model for other faith-based and community-based organizations to expand access to mental-health care. We’re creating a task-shifting model; often we’re taught that all the knowledge needs to be maintained within people who are degreed or lettered, but we want to empower our community to be able to give back to itself. With our Presence Project—a staff of lay mental-health workers trained in problem-solving therapy, mindfulness techniques, and cognitive-behavioral techniques—we can expand access.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. Grandma Ruby, J.C. and Me Watching Soap Operas in her Living room, 2007. From the series The Notion of Family. Gelatin silver print; 20 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

Dr. Esa Davis: I am an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. I am a researcher, physician, educator, and a community worker. I’m interested in how social factors can greatly affect one’s health, and I aim to understand the health-outcome disparities related to race and socioeconomic status (SES), particularly regarding obesity in women.

Some of the themes that emerged from my research were cultural differences in eating rituals, access to affordable healthy foods, and body-image norms. One striking study showed that African-American women were more likely to retain greater than fourteen pounds post-partum, compared to their White counterparts. This led me to work on understanding differences in how women go through pregnancy, coupled with determinants like poverty. When a woman comes into pregnancy with increased weight, she’s more likely to develop ailments like gestational diabetes, a type that occurs during pregnancy. A woman is more likely to have high blood pressure during pregnancy, and she’s also more likely to have postpartum cardiomyopathy, heart failure that happens during pregnancy. Some of those women end up in the ICU, some need a transplant, and unfortunately some of these women also die, which is devastating. From a recent study, we determined that women who are overweight or obese were much less likely to recover from this heart failure after six months, and because African-American women were more likely to be overweight and obese, it was one of the reasons why they were less likely to recover from heart failure.

In addition to my research work, I teach a population-health course for medical students, and together we run a poverty-simulation exercise every year. This gives the students an understanding of the challenges faced by working families struggling with poverty: when we physicians say they just need to eat right, exercise, and take their medicine, this is hard for many people, given what they have to do to manage their lives.

Discussion

LRF: Gabriel, in your book, you reveal that Columbia University didn’t have any interest in helping African-Americans, due to Jim Crow–era stereotypes about their docility. Could you talk about what it was like for families and individuals cut off through redlining, demarcation lines, and zonings?

GM: It is about limiting access, with lines of demarcation and exclusion based upon race. It’s important to grasp how segregated New York City was and still is. There’s a remarkable document, in the Wertham papers at the Library of Congress, written in fragments, that captures not only the state of segregation but also the unique approach that the Lafargue Clinic offered:

“[Addressing] the problem of Harlem racial segregation is the job of Lafargue Clinic. The public should be acquainted with the fact that discrimination exists in psychiatry. For example, the psychiatric institute does not take negroes as patients. Individual cases cannot be understood if the above points are not recognized. [The aim of] Lafargue Clinic is to do a higher type of psychiatry besides the ordinary ABCs, with political consciousness, defined by Dr. Wertham as ‘knowing what’s going on.’ Many who have the opportunity to know what’s going on do not accept it. No big theories are needed. No prejudices.”

At that moment, coming out of World War II, the behavioral and social sciences were dedicatedly anti-racist, against Nazism. In 1946, both the Lafargue Clinic and the National Institute of Mental Health were founded. After the success of the Lafargue Clinic, the Department of Hospitals opened a mental-hygiene clinic at Harlem Hospital, in 1947.

The Lafargue Clinic began operating in 1947, yet, it never got funding because it explicitly linked the social condition of anti-Black racism and class exploitation as possible sources of mental distress.

Installation view of the exhibition LaToya Ruby Frazier at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York (January 14–February 25, 2017). Photo: Thomas Müller. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome.

LRF: Wertham and Wright believed that the key to self-actualization could be found in socially and historically informed psychiatry. If social justice could be brought to psychiatry, mental health, and spiritual guidance, the inhabitants in Harlem—through their knowledge, self-awareness, and self-actualization—would be able to overcome conditions that are inflicted and compounded by racism, White supremacy, poverty, and exclusion.

What does it mean to bring democracy and social justice to your fields, so people can be empowered and achieve self-actualization?

ED: In medicine, each patient encounter can be a moment for advocacy. When I was a medical student, a resident presented a patient as, “This is Mr. So-and-So, a 60-year-old. He was noncompliant with his blood-pressure medications and he had a stroke.” The term noncompliance implies a judgment: the patient didn’t take his medication like he’s supposed to, and therefore his blood pressure went up, and now he has a stroke. After our rounds, I talked to the patient, and he said he had $200 that he needed to pay his rent. Because it doesn’t feel like anything when your blood pressure is too high—it’s a silent killer—he thought, “I feel okay; I’ll pay my rent this month. When I next get money, I’ll be able to buy medication, and then I’ll be fine.” From this conversation, I realized that we needed to figure out how to provide this man some medication that he can afford.

Social justice starts with helping medical students, through the poverty simulation and similar exercises, to learn how to listen to patients, to understand why patients are not able to follow instructions, to not be so quick to label them as noncompliant. We need to understand why they’re not able to do something, and we need to advocate for them. Because otherwise it leads people to debilitating and deadly results.

KF: Because of the stigma about mental health, it’s easier for people to seek support from their faith leaders rather than go to a psychiatrist or psychologist. I’m grateful that the current New York City administration recognizes that: Thrive NYC has been very supportive of the HOPE Center and the ways that people can receive services after their initial treatments.

Historically, religion has done a good job of controlling people. My research looks at how religious fundamentalism affects our identities and how we engage with one another. At the HOPE Center, we want people to express their agency, to create the lives they desire. In my office, I see the effects of a lot of adverse childhoods and how they play out in adults, such as exposure to chronic poverty, emotional or sexual abuse, and divorce. For people to have a space like the HOPE Center, and voice for the first time what they’re afraid of, is empowering.

For example, I’ve been working with a 76-year-old African-American woman for about four months. She was a victim of rape when she was sixteen and had a son as a result, which she did not disclose to him until he was 53. We spent our first three sessions talking about her anxiety and fear of the healthcare system and why she initially feared coming to the HOPE Center, about her experience of racial prejudice and how that affected her ability to access care. She told me about atrocities that she experienced, growing up in Baltimore and trying to get medical services, and how that discouraged her from seeking care.

According to a report by the Department of Health, people in communities of color typically wait nine years after a problem has been discovered to seek healthcare. That shows the stigma about seeking services and the issue of people not getting the help that they need when they go into many facilities.

GM: The Bard Prison Initiative is a program that offers a liberal-arts curriculum and Bard degrees inside six prisons throughout New York state. I am the associate director of the public-health program, which consists of a curricular specialization, followed by post-incarceration programs. The guiding light of the re-entry programs is a fellowship I run for formerly incarcerated individuals who are emerging as leaders in the field of public health. Currently there are eight fellows, who are extending the paradigms of healthcare through their growing expertise.

LRF: Under this current administration, we’ve seen the continued and increasing criminalization of poor people and people with mental illnesses; people don’t get a second chance at life after a single criminal offense. What are the challenges of this time, and what do you think needs to happen within your fields, within encounters that you have with patients or people in your communities?

ED: I think the elephant in the room is the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and what’s going to happen to it. In this country, we’ve always struggled over whether healthcare is a right or a privilege.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. Self-Portrait at 40 Holland Avenue, 2007. From the series The Notion of Family. Gelatin silver print; 20 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome.

It comes down to: Do we make sure everybody in this country is insured? And do we spend the money to do it? Other countries have solved the quandary through a single-payer system, which I believe is where we’re headed. Right now we have a two-tiered system: there is Medicaid coverage for those who have nothing, and there is a range of coverage for those who can afford it. But we have people in the middle: those people who are working but can’t afford healthcare, and if their employer doesn’t provides coverage, it is a serious challenge.

If we decide healthcare is a right, how much healthcare does one receive? If a young healthy person gets into an accident, what is our goal for care? Is it to restore a patient to as close to 100 percent? Do we do that for everybody?

We have to answer such questions as a society because we’re all going to pay for it. The idea of the Affordable Care Act was to pay for the care upfront, with everybody buying into and sharing the costs of the system. Now is an interesting moment: some people have health insurance, and no matter what rhetoric is offered, it will be very difficult to take it away. My husband is an African-American providing care in a hospital in rural Pennsylvania in a predominantly White, traditionally coalminer town. The expansion of Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act allows many people to see him at the hospital, but these same people voted for Trump and stand politically against the ACA. There’s a disconnection that I don’t purport to understand: in the same conversation, in the same breath, people who are benefiting from the Affordable Care Act are so against it.

My husband’s White patients think of Medicaid as benefiting inner-city Black families. In reality, more White people are benefiting from Medicaid than Black people, but those statistics are not promoted.

GM: It’s been shown that White viewers believe Medicaid advertisements on TV featuring White families are trying to hoodwink them, to steer them from away from associating Medicaid with Black people on welfare.

The real issue is the notion of bad faith. Lewis Gordon wrote a book called Bad Faith in Antiblack Racism. His idea is that when you tell a lie and believe the lie, you convince others that you’re not telling a lie, but ultimately a lie is taking place. And in this case, the lie is that welfare-chiseling Black folks are the main beneficiaries of government largess.

ED: The initial effort to kill the ACA failed because people who were benefiting from it came out in town-hall meetings and protested. They were not going to let their healthcare be taken away. It was a testament to people who put their political views aside to protect their healthcare. And it’s why politicians are going through back doors to try to dismantle the ACA.

Aside from the availability of insurance, the other issue concerns prevention, acute care, and chronic care. A lot of hospitals have been consolidating or downsizing. A lot urgent-care centers are opening. People who have insurance are encouraged toward preventive healthcare, receiving messages about eating right, exercising, and so on.

Hospitals are probably going to get smaller and become more regionalized and specialized, and we will likely see more outpatient acute-care centers. We’re moving toward the idea of empowering people to stay healthier: How do we prevent illness and heart attacks? How do we teach the value of exercising and eating right? And how do we incentivize people to do those things? The aim is for people to go to the hospital only if they really need to be there.

Now that more surgeries are minimally invasive, a lot of procedures that used to occur in a hospital can occur in outpatient surgery centers. More of the outpatient community programs and health-and-wellness and urgent-care centers are going to take place in the community, which will provide greater access.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. UPMC Global Corporation, 2011. From the series The Notion of Family. Gelatin silver print; 24 × 20 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

GM: I think folks should be focusing on two issues. One is the increasing role of non-clinicians in preventive care, with emerging models linked to evidence-based care and decreasing costs under the Affordable Care Act. The other is the importance of rooted psychotherapy and not simply prescribing medication. Reverend Kyndra, how are you navigating this issue?

KF: I became a clinical social worker to be a better spiritual leader. I think that psychotherapy and spirituality go hand in hand. When people come to the HOPE Center, they’re looking for answers: Why are they experiencing trauma? Why are they having tumultuous relationships? Psychotherapy is a way to talk about these questions, and every patient brings their spirituality with them. People navigate their traumas through what they’ve been taught to believe about themselves and about God.

I preach on a theme called “Lean into Life,” about leaning into freedom. What does it mean to be free? One answer that I’ve come up with is not to lean on the god that I grew up with, a god of the haves and the have-nots. That god said only Christians are welcome. This is what I was taught, and many of us carry implicit biases from what we’ve been taught to believe in religious contexts.

My challenge as a spiritual leader is to look at how we all have internalized this White supremacist world that we live in and how we can do the intentional work of being aware of our implicit biases, so we can end the cycle. Because I believe that we all come from the same spiritual place; we are spiritual beings living a human experience.

LRF: Tying this all back to The Notion of Family: the way doctors treat patients and their family members must be addressed. Even if there’s universal healthcare, there’s still bias and prejudice, especially when doctors interact with people who are living below the poverty line. What happened to me this past year, going through a racist and sexist experience with a doctor who wasn’t helping my mother, left me in psychological pain. No matter how many degrees or awards you may have, if someone discriminates against you and doesn’t see you as an equal or a human being, they will hurt you the most.

Dr. Esa was an eyewitness to a meeting that I had with all the physicians, the caseworker, and the social worker, who weren’t very happy that I was able to harness enough power and intellect to call this meeting.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. Mom and Me, 2008. From the series The Notion of Family. Gelatin silver print; 24 × 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

ED: I think this meeting happened because LaToya reached for advocacy. I knew that she was very frustrated. Her mom had been in the hospital for two weeks. We were finally making progress, and we needed to plan the next steps. But there seemed to be a rush to get her mother out of the hospital and into a facility that the family did not want her to be in, even though there were other facilities that were appropriate for her.

What made the situation difficult was that some medical assessments weren’t concluded, but the staff wanted to discharge her, and LaToya and I felt it was unacceptable. Unfortunately, a common problem is hospital-team transitions: a primary team makes certain decisions, but the next team isn’t aware of decisions that were made or the reasons behind those decisions.

We needed to get everybody to sit down together, because the social worker would tell LaToya one thing, the primary team would tell her something else, and the nurse would say something different. I talked with the primary doctor and said, “Look, the family needs to have a plan. You need to assess what their understanding of their mother and her situation is, and then you need to say what her condition is. What are the assessments that still need to be done? We all need to be on the same page when we walk out this room, with a plan that the family is comfortable with.”

I had prepared LaToya with questions that she needed to ask about her mom. At the meeting, she had her notes, and her brother was on the phone. LaToya stated her frustration and asked if we could explain a list of things.

LaToya asked the psychiatrist about the choice of the facility. The psychiatrist—who was not a person of color—said, “Well, I’m also a person of color, and I don’t necessarily make the same decisions as your mom would’ve made.” I almost choked because the psychiatrist’s experience has nothing to do with LaToya’s and her mother’s decisions. It revealed the preconceived biases or judgments that people have.

People working in medicine don’t listen enough. And we don’t separate what we may think and experience from the patient in front of us. We’re getting better; there are medical-school programs that are helping us to understand the patient, to put the patient at the center, and to avoid the paternalistic approach that physicians have normally had.

LaToya was wearing a black trench coat, and one of my colleagues felt threatened by her and called security. I later said to him, “We said what was going to happen, and in a half hour that plan changed. You made a different decision, you didn’t inform her, yet you wonder why she’s confused and frustrated, and you feel threatened by her appearance and call security. We need to fix this.”

He was like, “Okay, just tell me how.” I said, “First, you need to reverse all of this stuff that you’ve set in motion, which is discharging LaToya’s mother when she’s not supposed to be discharged. Then, you need to call the family and tell them that we’re sticking to the original plan. And then you need to let LaToya be with her mother. We do it for other families; there’s no reason why we can’t do it for this family too.” I said, “Do you understand that this is why health disparities happen? This is what undermines people’s trust in us: we say one thing and then we do something different.” I said, “We would not have done this if this was a White family. We would have gone on with the plan.”

And so, he apologized. He got it fixed. This is why it’s important to have different perspectives in the workforce. I was able to call my colleague to the floor. I did not do it in a threatening or humiliating way because that wasn’t the purpose. The purpose was to open his mind and help him do better and to be honest about the conversation, to say we can do better by these families.

Hopefully he will never forget that moment and he will never treat another family member like that. I believe he’s a good doctor, but I think a lot of things got in the way.

Installation view of the exhibition LaToya Ruby Frazier at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York (January 14–February 25, 2017). Photo: Thomas Müller. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome.

LRF: But they did call security on me. My mother was really weak and sitting in her chair, but she was screaming, “Don’t take my daughter!” Four male officers surrounded me, and the one who was the most hostile—a White guy in his forties with a crew cut and glasses—looked at me with pure hatred and tried to grab me from behind. My mom was panicking and started to cry. It de-escalated when a White female officer entered the room and said, “I’m sorry but you’re going have to come with us. Let’s calm down.”

The doctor escalated a situation after deciding, based on my appearance, that I was not an equal or intelligent enough to have called that meeting and spoken to them the way I did. The doctor reported that I physically assaulted him, which I never did. I fought back my rage and tears; the female officer looked at me and knew that I didn’t touch him. That doctor’s exaggeration almost caused me to be attacked by an officer and arrested in front of my mother, who was helpless and weak. And it was because the insurance company didn’t want her in that room anymore, but the team hadn’t cleared her to leave. I think the lowest blow was that they refused to let me come back that day.

This exhibition marks the anniversary of that day. It’s been nine years since my grandmother’s death, one year since my mother beat life support and defied expectations, and one year since I experienced that with her with these officers and this particular doctor.

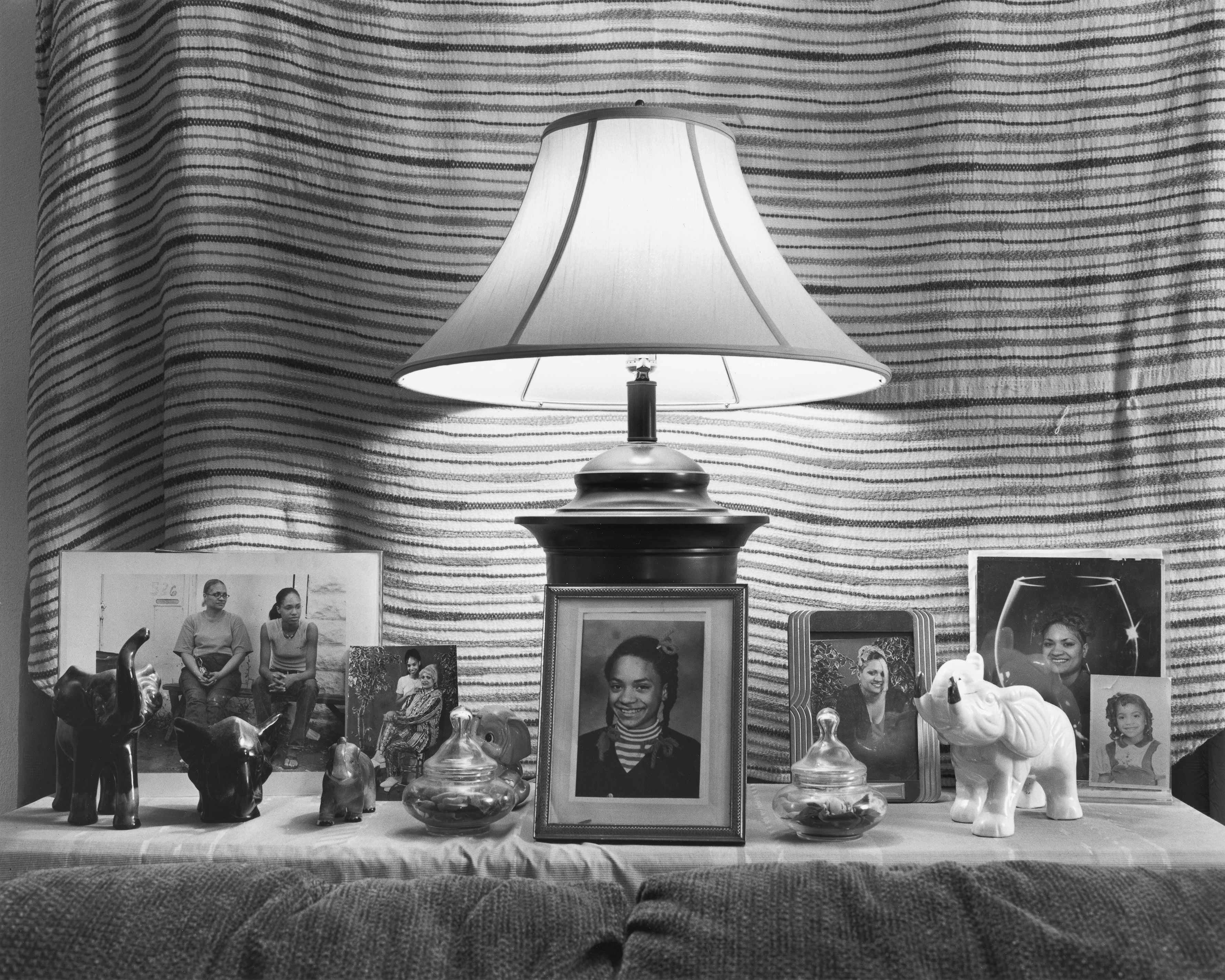

LaToya Ruby Frazier. Mom’s Pictures and Knickknacks, 2010. From the series The Notion of Family. Gelatin silver print; 20 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

Reading about the Lafargue Clinic, thinking about the HOPE Center being a contemporary example of that, and meeting Dr. Esa through the artwork—in a way, we’ve already collaborated. By tying the arts in with doctors and intellectuals, and people doing faith-based intercession, it is possible to save an individual’s life and a family from being pushed over the edge.

We all need to feel more empathy. Living under capitalism and White supremacy is really an attack on equity. This is a difficult conversation, but I hope that everyone will think about these questions: What are you doing for others, and who are you surrounding yourself with? Are you part of the problem? What are you doing to fight for equity?