Adam Golfer—Neither one of us had ever worked on a film about a group of artists whose practices are all very different, but operate together as a collective, and come together for a unified purpose. After meeting with the collective I Wanna Be With You Everywhere (IWBWYE) for the first time, it became clear that to achieve the bonding and the intimacy that would often come about naturally in the single-artist profiles that Art21 produces would require a much longer gestation and a new approach.

Andrea Chung—I often think of making an Art21 film as finding the right balance between three main components: an interview with the artist, some artmaking process, and an experience of their artwork. When we first started working with IWBWYE, they generously invited us to take part in a few of their weekly Zoom meetings, which were instrumental in shaping the form the film would take. They helped us realize that in a film featuring the collective, the three main components of an Art21 film would necessarily intertwine. These Zoom conversations not only serve as the artist interview, but are also the collective’s process and the art they create together. And so the challenge for us as filmmakers became, how do we convey that in the film in a way that feels true to the collective and their ethos of building cross-disability communities?

AG—Initially, we were nervous that there were only two opportunities to film with the group in person: at the rehearsal of their Summer Solstice gathering and at a Touch Tour they organized at the Whitney Biennial, where two of the collective’s members, Carolyn Lazard and Constantina Zavitsanos, were showing work.

At the Solstice rehearsal, we met everyone in real life for the first time. The event is a big program that they do every two years or so. They invite friends from various cross-disability communities to take part in performances and spend an afternoon together. I was struck by how joyful it felt.

There was a big turnout at the Touch Tour, and everyone seemed so happy to be in a space that was focused on not only experiencing Carolyn’s and Constantina’s installations, but also geared towards their needs.

Once we did the two in-person shoots, we felt a lot more confident that we had a film that could move between their virtual relationships and their in-person engagement at events. It also made us realize that to the collective, meeting in person is just a fraction of the work that they are doing to organize. The work before and after the event or gathering is just as important as the thing itself.

AC—When we met the collective for the first time at the Solstice rehearsal, the thing that struck me the most was seeing how they interact with each other, how they work together, and how that’s the way they care for each other. After that shoot, for a while, our working title for the film was Measures of Care. We were struck by the intention behind everything they do. There is so much thought and consideration behind it.

That influenced how we thought about the film and how we made it. We put a lot of care into it, because that’s the example that they showed us.

AG—Each time we met with IWBWYE, whether in person or virtually, we gained a deeper understanding of what accessibility means to them. It was an eye-opening education for me to be exposed to a very new way of considering what the word “accessibility” means, unpacking how it’s commonly used, versus the potential of what it could mean.

The more time we spent together, the more the collective trusted that we were really trying to think about and keep their interests and concerns at the forefront of the project. And with that understanding as our foundation, we started to experiment with the form of the film. I don’t think we really knew what the film would look like until we were halfway through working on it. That’s partly because the collective was like, “It doesn’t matter what it looks like, it matters what it is.”

AC—It’s the ultimate “trust the process” kind of project. That said, I feel like you had a pretty clear vision from the beginning, or at least before the Touch Tour, when you were like, “We’re going to shoot this in multiple cameras and we want it to feel like textures. It’s not necessarily about documenting things perfectly; it’s about capturing the atmosphere of the event.” I wonder if you want to say something about that.

AG—The collective shared a lot of resources and references that inspired us to break the mold of how we thought films should/could be made. One film everyone cited with reverence was Jordan Lord’s 2018 short, After… After… (Access), which deals with intimacy and accessibility, and how you can express things narratively in a different way by incorporating audio description (AD) or open captions, so that these components—which are too often slapped on at the end of the filmmaking process as accessibility “features”—become an integral part of the storytelling.

I was interested in embracing a sort of high-low approach where we sometimes shoot with more traditional cinema cameras, and other times smaller cameras or maybe phones that would allow us to get outside of the “authoritative documentary view” that is often the default for this type of project. I don’t know if we 100% delivered on that idea [laughs], but we did use multiple cameras and tried to find new forms that did not prioritize the visual. For example, there are a few sequences in the film where different voices are speaking, and you’re literally seeing words pop up on a solid color background. That ended up motivating how we structure the film, and it felt exciting to intercut that with the AD that courses throughout the film.

These types of realizations opened things up for us to not obsess about perfect formal decisions with lenses and light, but to think more about what is being said, and what we are feeling as we listened, and trying to give priority to voice over observation.

AC—We knew from the start that we would incorporate AD to help make the film more accessible, and as we gained a better understanding of the collective’s practice and ethos, we got excited about experimenting with AD as the narrator of the film. We worked with a professional audio describer and a Blind Quality Control consultant to write and rewrite the script, and gradually the AD evolved into a character in the film. It’s not the typical “voice of God” narrator that knows everything, but rather, it’s kind of like us giving back parts of our journey to the viewer so they can come along for the ride.

During the editing process, you recorded temporary AD so that we could figure out the right timing for how long to hold shots and the overall rhythm and runtime of the film. When we showed the collective the first fine cut of the film, they commented on how much they loved your voice as the AD because you’re kind of involved but also removed. You’re a part of the group, but also not. We were going to hire someone to record the final AD, but ended up running with your recording and kept it as a part of the film.

AG—Which makes me nervous because I’m not a voice actor [laughs]. But at the same time, there’s a meta aspect of us directing it and one of our voices being the description of what’s happening on screen. That felt meaningful to me because it came from within the project. We discovered it instead of deciding from the beginning that that’s what it would be.

AC—There are a lot of things that kind of evolved naturally in the process as we worked with the editor, Danya Abt.

We added a pre-roll at the beginning of the film, which is an accessibility tool that allowed us to set up the basic context of who, what, where, and some of the formal choices we made. Usually, it’s for blind and low vision audience members, but in the case of this film, I think all viewers can benefit from taking in the premise of the film in a very clear way in the beginning.

AG—Once we wrote the pre-roll, it became so much a part of the language of the rest of the project, and seemed to tie everything together. It felt generous as opposed to withholding. I really appreciate that ethos as a standard.

AC—Another thing that came up in the process was using color backgrounds in the multi-channel sequences. This element came pretty organically when Danya was editing, and it adds to the feeling of abundance in the film for me as well.

AG—Absolutely! We tinkered with using multi-channel imagery in the observational scenes so that the viewer is constantly invited to see through multiple perspectives at the same time. I also became really attached to using the multi-channel format during the interviews. The classic documentary language is to cut between a wide shot and a close-up of interviews, but the multi-channel layout gives a sort of simultaneity to everything. You always have one eye on the group and one eye on the individual, and that feels true to the way IWBWYE functions as a collective. They bring all of their own perspectives and experiences to the group. And so the conversation becomes “the work.”

AC—There is a lot of conversation, and a lot of different voices in the film. But it’s also a lot of listening. I mean, it’s a collective steered by six artists, so one-sixth of the time you’re speaking, and the other five-sixths of the time you’re listening. Perhaps that’s where the magic happens.

I think that’s true in our collaboration with Danya, too.

AG—The three of us really had to trust each other, and we became this little committee where we constantly interrogated ourselves about whether we were doing justice to the things we said we were trying to do. We all supported and checked each other when we weren’t sure about decisions. That was also a really special relationship for a year.

AC—A few months into working on the film with the collective, they shared that they sometimes think of their process as a romantic comedy. They’re striving for a happy ending, and while there are challenges and problems to solve along the way, there’s also humor and laughter. I hope the film conveys that feeling.

AG—And what they said about how there’s not one perfect way to do anything–that means sometimes things get messy, and that’s okay.

Andrea Yu-Chieh Chung and Adam Golfer

Directors, “I Wanna Be With You Everywhere”

IMAGE DESCRIPTIONS

-

- Image Description: A screenshot shows six people on a video call, arranged in two rows of three. Everyone is smiling or laughing, creating a joyful and relaxed atmosphere. The background includes a mix of home and office settings, with a bright blue border framing the image.

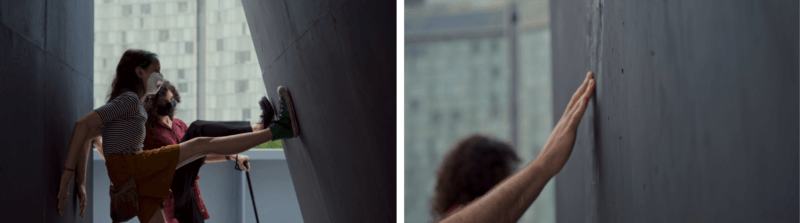

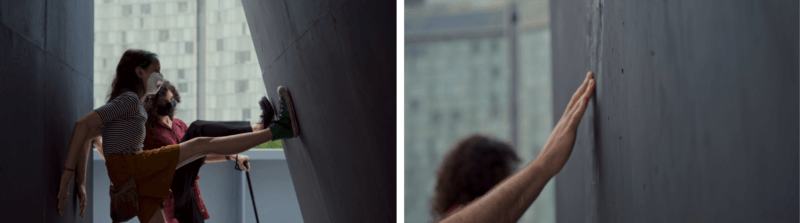

- Image Description: The image consists of two side-by-side photographs. The photograph on the left shows two individuals engaged in a dynamic pose against a tall, dark, smooth wall. One person, with shoulder-length hair, sports a striped shirt and mustard shorts, and has one leg extended, pressing a green sneaker against the wall. The other person is partially obscured, wearing a burgundy top and black face mask. The background reveals a large, out-of-focus building with multiple windows. In the photograph on the right, a close-up shows a person’s arm reaching out, with their hand touching the same dark wall. The focus is on the texture of the wall with the background softly blurred, showing hints of a grid pattern.

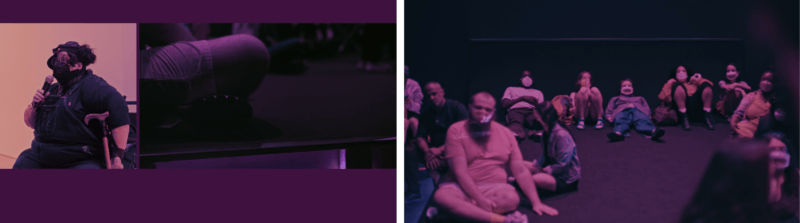

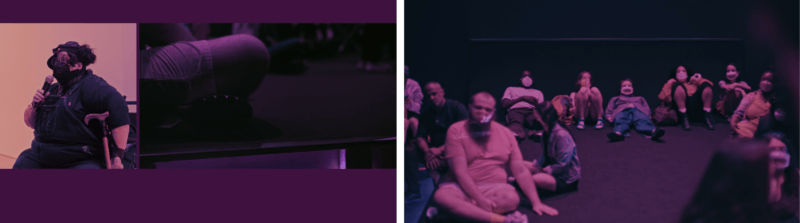

- Image Description: The image on the left is divided into two sections. On the left, a person wearing a dark outfit, including a mask, glasses, and hat, is seated and speaking into a microphone. They hold a wooden cane and are situated against a softly lit background in warm tones. On the right, a close-up of a person’s leg and knee is captured in dim lighting, positioned on a dark surface, creating a high contrast with the soft illumination visible at the bottom edge. The image on the right shows a group of people seated on the floor in a dimly lit room, all wearing masks. The individuals are spaced apart, some sitting cross-legged. The room has a dark, minimalist backdrop.

- Image Description: The image is divided into two sections side by side. The left section has a bright yellow background with black text aligned to the left. It details a short documentary featuring a six-person artist collective called “I Wanna Be With You Everywhere.” It mentions the filming locations: Performance Space and the Whitney Museum in New York City, and describes the collective and their collaborators as a multi-racial, multi-gender, cross-disability community of artists. The right section has a dark teal background with a single line of white text in the center, reading “that’s really what we want.”

- Image Description: A screenshot shows six people on a video call, arranged in two rows of three. Everyone is smiling or laughing, creating a joyful and relaxed atmosphere. The background includes a mix of home and office settings, with a bright blue border framing the image.

IMAGES: Production stills from the New York Close Up film, “I Wanna Be With You Everywhere.” © Art21, 2025.