Interview

Political Humor and Colonial Critique

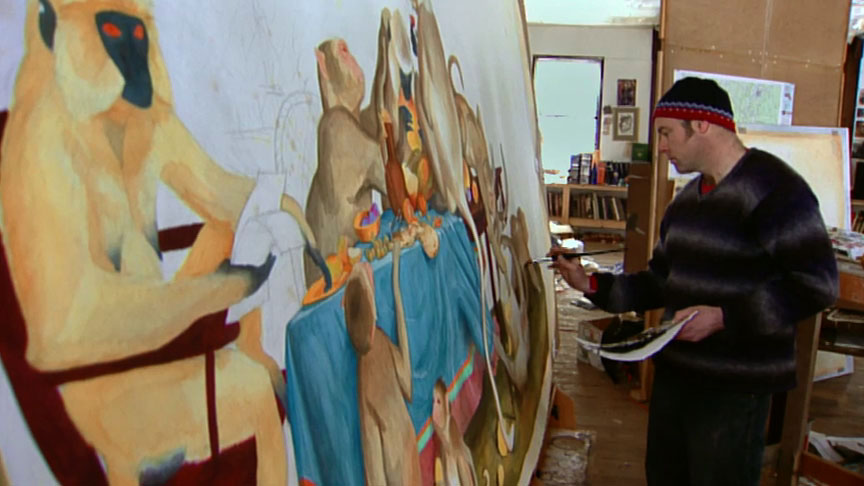

Walton Ford at work on The Sensorium (2003) in his studio, Great Barrington, Massachusetts, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Humor. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Artist Walton Ford discusses his work’s relationship to colonialism and political humor.

ART21: Can you talk about the series of paintings you’ve been working on that deal with Sir Richard Burton?

FORD: I have this ongoing project that has to do with this African explorer, Sir Richard Burton, who I actually have pictures up on the wall in my studio. He was one of these 19th Century explorer guys that I’m particularly interested in. And he was a complete lunatic. He was a linguist and knew something like thirty or forty languages by the time he kicked. He translated the Kama Sutra into English. He translated The Perfume Garden. He spoke Arabic and Hindustani. He spoke many languages very well, to the point of being mistaken for a native. He was stationed in India in the 1840’s, during the Raj, as an English officer. And he was able to penetrate Mecca in disguise as some sort of Persian trader or something. And he had all these aliases. He was a spy. He was part of the great game—the whole kind of thing that Kipling talks about in Kim.

The painting I’m working on now is a monkey banquet. It has something like nine or ten monkeys so far. I’m going to put more in. And it’s part of a series that has to do with Burton. He’s an endlessly fascinating character for me to study. But one of the stories that I was reading about him that stuck with me was this one about these monkeys that he kept in his quarters when he was a young British officer. And I’m going to read a quote that explains the painting:

“His language studies continued unabated and his interest in the science of the spoken word led him to conduct an interesting experiment with some pet monkeys. Curious as to whether primates used some form of speech to communicate, he gathered together forty monkeys of various ages and species and installed them in his house in an attempt to compile a vocabulary of monkey language. He learned to imitate their sounds, repeating them over and over. And he believed they understood some of them. Each monkey had a name, Isabel, his wife, explained. He had his doctor, his chaplain, his secretary, his aide-de-camp, his agent, and one tiny one, very pretty, small and silky looking monkey he used to call his wife and put pearls in her ears. His great amusement was to keep a kind of refectory for them where they all sat down on chairs at mealtimes and the servants waited on them and each had its bowl and plate with the food and drink proper for them. He sat at the head of the table and the pretty little monkey sat by him in a baby’s high chair.”—That’s just too good!—”He had a list of about sixty words before the experiment was concluded, but unfortunately the results were lost in a fire in 1860 in which almost all his early papers perished.”

And to me, this is just what I’m looking for when I’m doing all this reading. I do a lot of research and this thing has almost everything in it. It’s like a mini-history of colonialism right there, of the imperialist venture. He’s learning all the languages he can. He’s possessing as much of the culture as he can. There’s an erotic kind of fascination to it, like he’s got his wife. The whole thing is so wild. And yet there’s something sort of futile and hopeless about it. And then the whole thing goes up in flames. I mean it’s almost the history of the British in India. It’s too good!

So the painting I’m working on now is Burton’s refectory, his amusement. And I’ve got the wife in the painting. The doctor, the aide-de-camp, the chaplain—they’re all in there. And I’ve assigned them all little personalities of their own. And as I was working on it, a little subtext crept in and I went with it—which is the painting is also an allegory of the senses. I have sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound in there as well, mixed in with the things. It seemed like the senses come to play in this sort of colonial experiment too. You know he’s just trying to experience…. Burton was one of the, great British minds and was endlessly curious. He wasn’t one of these people that talked about “bloody wogs.” It was more like he really wanted to understand the cultures he was immersed in. Not in an enlightened or politically correct way, but in a way to better serve his country and his cause, to serve this sort of empire. But head and shoulders he’s more interesting than most of those guys. They looked down their nose at him and called him “Dirty Dick Burton.” They found him sort of filthy because he was so interested in the erotic and was interested in researching brothels and things like that. A little more than what made his mates comfortable over there.

Walton Ford at work on The Sensorium (2003) in his studio, Great Barrington, Massachusetts, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Humor. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Is there something about colonialism that’s inherently humorous to you? I don’t think most people would find colonialism very funny.

FORD: That’s a good question because I feel like on some level I’m personally acquainted with some of this material because my family was from the South and I’m descended from slave-owners. I was interested in confronting that aspect of my background and making pictures about it. So for a while I did try to do that. This is a more indirect way, you know, not directly making pictures about my people so to speak. But I’m interested in finding a way into this material.

I think that there’s almost no subject that you can’t treat with some humor, no matter how brutal it can seem. And that’s just something that I see in Goya or Brueghel or people like that, or even R. Crumb, or somebody where the subject matter is pretty intense. With Goya, he’s talking about a Spanish inquisition, but to do it he’s got a parrot or some sort of weird animal allegory functioning that has to do with bulls falling from the sky or something like this. Brueghel is the same way. Like if he’s dealing with some dreadful sin or cruelty, there’s room for a sort of droll approach in his mind anyway. And when I was thinking about my ancestors there was something kind of pathetic about them. Like one series of paintings I did—and it’s not that I necessarily want to call attention to earlier work, but it all leads to the approach that I have now—was painting ancestors of mine on horseback but losing control of their horses. And I know enough about riding to know what you’re supposed to do. Not that I’m a good rider, but I’ve ridden horses. So the idea being that these guys were losing their stirrups and they’re sort of slipping from the saddle. But the whole equestrian tradition has to do with mastery of a spirited animal and with control, and I wanted to subvert that.

So my humor is a bit at the expense of the Empire. And I feel like I can be the brunt of my own joke. And I don’t see any reason not to do that, to poke fun at my own culture, to poke fun at my own foibles. And kind of feel like I’ve earned that at the very least, you know. There is another book, the The Autobiography of Emily Donaldson Walton, and she is someone who remembers the plantation. I’ve always had this book and this is what she wrote when she was in her nineties. And this is in the 1930’s. So she’s someone who remembers Sherman’s march on Atlanta. What’s amazing about my family is that, for example, my brother who’s six years older than me, there’s a picture of him sitting on my great grandmother’s lap. Now my great grandmother remembers when Sherman marched on Atlanta when she was about six. My brother was twelve when the Beatles played at Shea Stadium. So the overlap there is just insane, how compressed the history is.

I’m very interested in addressing this stuff. I think we had some very grim political art in the ’90s that was photo or text based and absolutely humorless. And I don’t think people benefit from that tone of voice. I think the best antiwar film ever made is Dr. Strangelove, period. And so much better than something like Schindler’s List, which will just make you feel so sanctimonious and it’s just—who needs it? That’s my take on it.

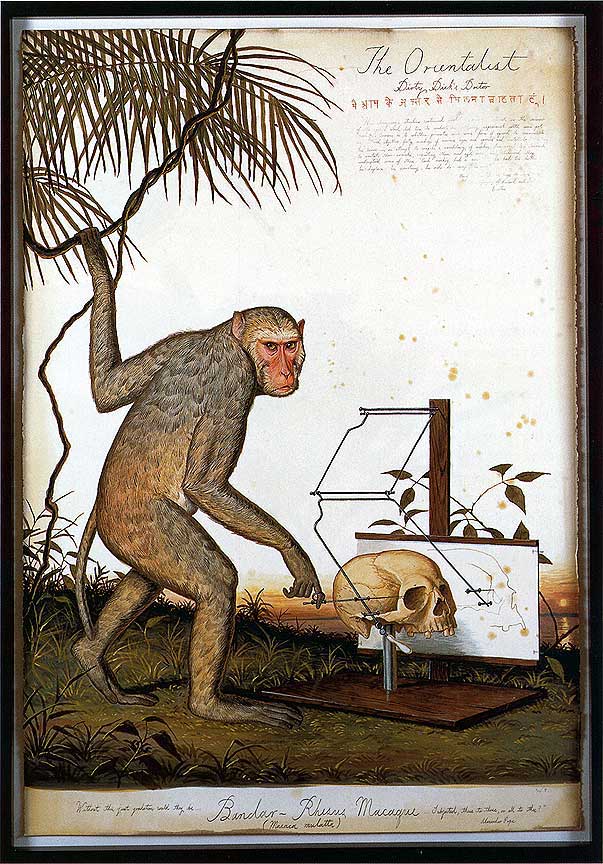

Walton Ford. The Orientalist, 1999. Watercolor, gouache, ink and pencil on paper; 60 × 40 inches. Private collection, New York. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York.

ART21: What’s particularly humorous about British colonialism?

FORD: The thing about this monkey picture is Richard Burton is keeping forty monkeys in his quarters when he’s a young officer to learn their language. There’s something just right away that strikes me as humorous in the quintessentially super-eccentric British way and their mode of building an empire which was carried out by these kinds of eccentrics.

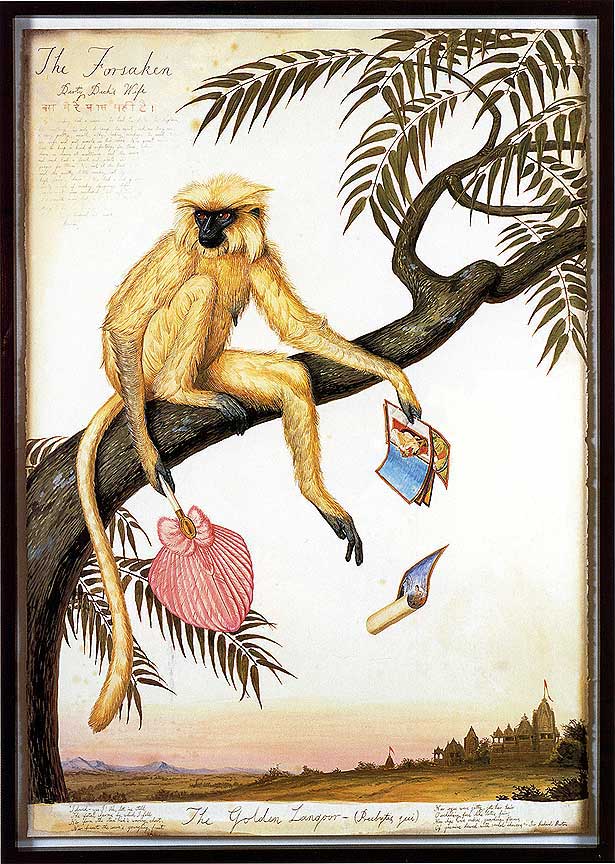

There is just some sort of sad humor in this idea. When I painted the monkey wife, I painted her individually and I named it The Forsaken. And my idea is that what Richard Burton did as part of his colonial enterprise was to actually learn languages. When he would go to a new place he would have a woman set up house for him and become his mistress. And he said he would learn the language that way.

So this thing with the monkey wife seemed to be perverse once you know that about him. I set up a fantasy that she was devoted to him, that she really loved him. And when he left she was a bit heartbroken to no longer to be his wife. In the colonial experience as it happened in India, it was almost as if India was caught in an abusive relationship with some sort of male. That’s how it always was portrayed. What England held was feminine and what England was was masculine. Then when they get out of the relationship, there’s some sort of bereft quality to the place once you leave. So it mocks that idea, as if this monkey could care less. So she sits in a tree and she’s got Indian miniatures that are erotic and she’s got a fan, a pink fan, and she looks all heartbroken and bereft because she’s been abandoned by her lover—which is how England would like to think the rest of the world felt about them, the sun setting on the Empire.

ART21: Is there a word for that kind of humor that you apply to your work?

FORD: I guess it’s satire or parody or any of that. And then there’s this idea of sending up the whole form of discovery. In other words, the mode of representation that I use looks like 19th Century manuscript painting. It looks like the kinds of notebooks that these colonial guys kept where they did sketches of the local fauna and flora, and named it after, you know, themselves and their own friends and colleagues back in England or whoever first described it. It wouldn’t matter that it might be known for thousands of years in the culture that was already there. These guys got the opportunity to call it “Johnson’s this” or “So and So’s that” and give it a Latin name and file it.

So I use those modes of representation to paint these things as well. That turns that tradition a little bit on its head. Rather than in the service of these great collections or empires, it tells an alternative narrative. All of this makes it sound like I have this great intellectual reason for making these things, but ultimately I want to paint a sexy monkey, and I want to paint a big, huge elephant with an erection. And there’s this other sort of silly kind of underground comic aspect to me that just wants to paint this stuff.

And it also comes from some personal inner reason that has nothing to do with this sort of other thing. I often question the intersect between the message as perceived (as a political kind of “blah, blah, blah”) and my urge to just make these pictures. Why do I feel the need to make these things? Why is it that you want to make them as disturbing as you can? Or as violent and out of control as you can? That just comes from some place that doesn’t bear up under theoretical discussion. And all artists are like that. They get going and then they figure out—as they go—why and what it all means in a weird way, and how it all ties in.

I think I’m explaining it to myself with these slave-owning ancestors. What exactly was it about, going down South when I was boy? Was it seeing the end of that kind of thing? I was born in 1960, so when I was a tiny boy in the South it was a very different place. And we used to go down all the time to see my grandmother in Georgia or my relatives in Virginia. So I think maybe that had something to do with it. And in Virginia there’d be this duck hunting and turkey hunting kind of milieu. There was the great kind of southern gentleman, naturalist sportsman tradition in my family that was still being kind of held onto in spite of the fact that most of family’s wealth was, of course, gone with the wind…thank god.

Walton Ford. The Foresaken, 1999. Watercolor, gouache, ink and pencil on paper; 60 × 40 inches. Private collection, New York. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York.

ART21: There’s always that mixture of glee and revulsion in your work. Can you talk about that some more?

FORD: The big, big thing I’m always looking for in my work is a sort of attraction-repulsion thing, where the stuff is beautiful to begin with until you notice that some sort of horrible violence is about to happen or is in the middle of happening. Or that it’s some sort of interior monologue.

Take a figure like Audubon, who was kind of a madman. He was violent. If he didn’t like you he might challenge you to a duel or something. I mean the guy was completely out of control and shooting birds off the deck of ships and watching them drop in the ocean. On a riverboat trip down the Missouri he’d shoot a coyote and wound it and it would run off into the hills and he’d never see it again. He wasn’t the enlightened sportsman that we’re used to thinking about. Often when I paint something in his style, I try to think that it’s almost like his dream state or something. It’s like the way he really thought somehow betraying itself and leaking into the work, infecting it somehow, giving it a computer virus and making it do what it oughtn’t do. Or what it shouldn’t reveal.

When you look at the Audubon painting of the passenger pigeons, he just paints two little romantically involved passenger pigeons. And there’s no implication that there were billions of these birds that were getting reduced by the largest single slaughter ever above the water vertebrates. You have no idea that everyone was engaged in this wholesale slaughter of this bird. There was a whole economy built on destroying these birds and within fifty years they were all gone. That was something that these guys didn’t allow into the work somehow. And that’s what I put in the work. I want to tell that story.

Walton Ford. Falling Bough, 2002. Watercolor, gouache, ink and pencil on paper; 60 3/4 × 119 1/2 inches. Private collection, Tennessee. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York.

ART21: Is subverting the norm something that you adopted from experience or did it come from looking at art? Were you a subversive child?

FORD: I was impossible, man… I came out of that generation that turned into the punk movement. It was partly that. There was this sort of moment in time when you weren’t a hippie anymore. And you certainly weren’t going to be a Reaganite—this is the generation that has SUV’s and made up the idea of a five-dollar cup of coffee and voted all these Republicans into office. And I’m supposed embrace this bunch of clowns? I felt that when I was a little kid. There was nothing cool about it.

I was way too late for any kind of feeling of cohesiveness with the ’60s. And by the time I was old enough to notice these guys that I thought were cool when I was young, they were all burnt out or dead. So I had no interest in being one of those guys. And then I couldn’t do the punk thing because that seemed too much like joining. That felt so militaristic and lockstep. So there was this sort of ironic distance you adopted in your twenties that had to do with a sort of arty, snotty distance that you see in like the Talking Heads back in those days. And I could kind of relate to that, but you just didn’t know where to stand. And so yeah, there was some idea of taking respected modes and screwing them up.

One of the things I think that confused people about my work when they first saw it in New York was how close it is to duck stamp art. Or the thing that you would put above your living room couch. A very accepted mode and conservative mode of representation. And that’s deliberate, but that was misunderstood and it’s still misunderstood. I still have trouble breaking down that last barrier to understanding my work. There’s an innate suspicion that some people have of craft, of being able to paint or caring or giving a damn. Not forging ahead in that modernist tradition of breaking new ground and using new media. The fact that I would much rather paint in ways that have been tried and true for hundreds and hundreds of years. There’s so much bad art that’s made that way and it’s hard to make people understand what I’m up to.