Interview

Earliest Influences, Early Works

Vija Celmins. Night Sky #10, 1994-1995. Oil on linen mounted on wood; 31 x 37 1/2 inches. Private collection. Photo by John Bigelow Taylor. Courtesy of McKee Gallery, New York.

Artist Vija Celmins discusses her upbringing and early influences on her work.

ART21: I’m curious about this old painting you have in the studio. Have you been thinking about its qualities, in terms of what you’re working on now?

CELMINS: Well, I did this painting about 1965. I was going to do a show, so I had it out, and somebody was writing something. I actually took it out about a month ago, to show this person from London an early work. I think I painted this in the middle of the Vietnam War. I was sort of remembering the planes when I was in Europe myself, in 1944, just a small child. I remembered the airplanes. I’d never seen one, of course, but I heard them, you know? They were this sound. There was something thrilling about it—I always liked airplanes—and then, of course frightening. I’d seen them in World War II, and I painted it during the Vietnam War. We have another war now. It’s sort of like an image of a war machine. It’s quite beautiful, in some ways, and kind of a dramatic image. It came out of me painting objects—single objects on the still life—and then I sort of shifted, like I tend to do every now and then. I shifted to painting objects that were found in photographs that were no longer objects now but machines. Mostly airplanes. I think of them as sort of still lifes, still.

What’s kind of amazing about this painting right here, now, is that my recent work is so more intellectually mangled. There’s something more intellectual, in a way, with more of a pressure of the mind on them. They’re so flat, and this painting has such an illusionistic space in it. I think I remembered kind of feeling the joy of being able to paint anything. At that time I painted a lot of different objects, things that turned on, like my hotplate and the lamps. Things that I had—pretty much everything I had in the studio. Then I started painting images of little clippings, and this is one of them. So, I liked the painting. I’m trying to see whether it can hold up to my having had maybe thirty-five years of painting after it. I still like it . . . I don’t know . . . maybe I like it. It still seems like a pretty strong painting.

ART21: I’m interested in the fact that you held onto it for so long, that you didn’t let anyone snatch it away.

CELMINS: Well, I saw that some people were beginning to buy these works—and thank goodness nobody wanted this one by the time I came around to valuing it myself a little bit. I had a habit of painting and throwing work away because I thought that the painting part was where I learned things and went through things, and I didn’t pay that much attention to the painting afterwards, sometimes. I would throw away a lot of work, and I kept this one, so that’s nice. What can I say? I mean one of the things that it has is that strange quality of being kind of flattish and also illusionistic. Of course, it’s more illusionistic than the work I do now.

ART21: They both seem to have a complete stillness.

CELMINS: One of the things that I guess is sort of interesting is that the airplane is moving, of course, and is up in the air, and yet it has this certain very still quality. Of course, I think stillness is one of the pleasures of painting—that it’s a surface that doesn’t move and that is still.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Time.

Segment: Vija Celmins. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: What about time? Your work seems to have something about time or timelessness.

CELMINS: I don’t know. I really can’t tell you about that. I don’t try for things like this. Sometimes, now that I’ve reflected back on my work, I see some of that in it, but it’s a quality that seems to be (maybe) because the paintings are so thoroughly realized. That’s not something that I ever think about.

ART21: In the making of the paintings—the kind of brushes, the kind of concentration and the amount of time it takes, and the sanding—to me, it all has a quality of meditation. Is there something about that that you like?

CELMINS: Well, I think I like the reality of preparing the canvas. I like to make that reality really real. I like the image coming and going. I like to sand the image off and have it come again. I guess it’s a kind of a futile attempt to put something in there that is sort of dense. Maybe you could say there was time. It’s certainly a record of time spent on one small surface, sort of shaping it over and over in slightly different ways, different days. In a way, it’s a kind of composing without composing. That’s what I can think of saying about it.

ART21: Do you think having the airplane painting in the studio influences what you’re doing now? You made art as a child . . .

CELMINS: I did a lot of drawing, of course. You know, we all did drawing; that’s how it started. You know, you’re little; you start drawing, just keep drawing. It sort of makes a certain kind of life. I guess drawing and reading—I used to read a lot. I made a sort of world. Read a lot, draw a lot—that’s what I used to do.

ART21: Did you parents encourage you?

CELMINS: No, they did not. I did it in spite of my parents. They were busy working. They worked very hard, and they didn’t pay any attention to me. I mean, they didn’t say, “Stop drawing”; they didn’t say, “Start drawing.” They left me alone, you know; it was the old-fashioned way. They didn’t pay any attention to it. I must have just gravitated that way.

I remember once, though, of asking my mother to draw a flower for me when I was maybe about seven, in the kitchen. This was in Germany. What was so wonderful is that I thought that she could do something that was really magical. And she drew this little pansy, which I’ve now planted around. I sort of like the pansy; it makes me remember my mother. And she was not a draftsman, but she drew this little pansy, you know—two little ears and one down and then a little face. Like pansies have a little face! I thought it was the greatest thing I’d ever seen; I loved it. I mean, who knows—maybe somehow I thought to myself, “I’m going to be able to do this sometime.” But I didn’t want to do it; I wanted her to do it. And my sister, I think, also drew. And my father also drew. We just did whatever. He drew plans for houses, and he built houses and did all that stuff. Nobody ever talked about anything like that, and we just left each other alone.

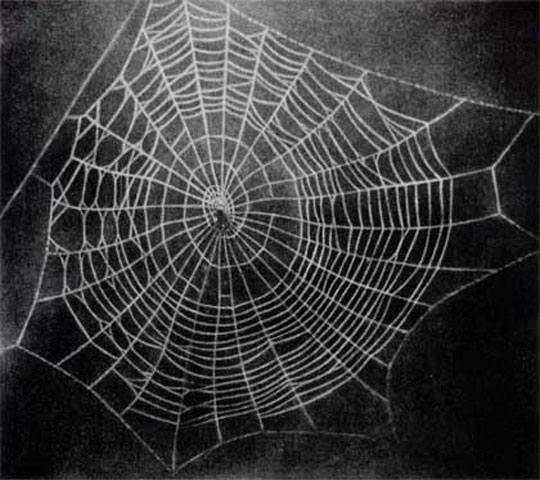

Vija Celmins. Untitled (Web 1), 2001. Mezzotint on Hahnemühle Copperplate paper; 23 × 18 3/4 inches. Edition of 80, AP of 12 numbered 1-12, and AP of 15 numbered I-XV. Published by Lapis Press, Los Angeles. Courtesy of McKee Gallery, New York.

ART21: Were there people along the way who encouraged you?

CELMINS: Oh, yeah, when I went to school in the United States, I really couldn’t speak English. And I couldn’t speak German either. But I didn’t go to German school; I went to Latvian school. I started drawing in Latvian school, but I don’t think they really encouraged drawing. I think they encouraged drawing and creativity much more here. They have a lot of rules about what children should do in Europe, if I remember correctly. I used to have to stay after school all the time. I was testing those rules. I sometimes used to stay ’til the night classes came in. And they’d say, “What are you doing there?” You had to face the wall, you know. And I had done something, like—who knows what I did—throw things.

In America, I used to draw all the time because I couldn’t really understand what they were talking about. So, I used to draw things, and then teachers were always encouraging me. But I guess that was something. I think teachers encouraged me to draw and paint, and I suppose that was something because we didn’t have the habit of doing that in our house, encouraging each other to do things like that.

ART21: And art school?

CELMINS: Yeah, and then going to art school. I mean, it turned out that maybe I had some gifts in that area, so I had a lot of encouragement. But I was also very rebellious and inward. I don’t know how to talk about it, you know. Something, I suppose, that many artists felt—sort of outside of society a little bit. Then when you go to art school, you feel like maybe you’ve found some place where you can feel a little better.

ART21: When you could speak English?

CELMINS: Let me see, I came when I was nine, so probably a couple of years later. I mean, I don’t express myself well; I never judged myself that way. I think I could speak English; I played with kids. When I came, they put me in the fourth grade. I think by the sixth grade, I was trucking right along.

Vija Celmins. Untitled (Big Sea #1), 1969. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper; 34 1/8 × 45 1/4 inches. Private collection. Courtesy of McKee Gallery, New York.

ART21: Are there visual things that inspired you early on?

CELMINS: Let’s see. I think I remember there was a picture of the opera house, in my house in Latvia. And when I was about twelve, I had a photograph of it on the wall, and I did a copy of it.

ART21: Is there an early painting that affected you?

CELMINS: No. I was sort of awed and scared of museums. It takes a long time to learn how to look at paintings. I didn’t know how to look at paintings. And it took a long time to learn how to sort of figure out what it was about and to see them. I don’t remember one painting that really, totally knocked me over until I went to Europe and I saw the Giotto chapel in Padua. That really knocked me over—maybe all that glorious blue or something, and just those little compartments with these extraordinary scenes in it. It was really a great work. I got turned on by a lot of art then.

Before that, when I was already in art school but very early, what did I draw? You know, I drew things that girls draw, you know. I used to draw movie-star pictures out of movie magazines. I used to draw horses, heads, and faces. I tried the really amateur stuff, dopey kind of stuff that children do. I guess a lot of kids now draw comics; I never really drew comics. I don’t know why—I love comics. I think I learned English from comics, looking at comics. I used to look at Nancy. She didn’t speak much, did she? Was it Tubby and Nancy? Or Lucy? Lucy had the head like a bean, remember? And Nancy had the hair, the round head with the little spikes in it.