Interview

Abstraction and “Ladder for Booker T. Washington”

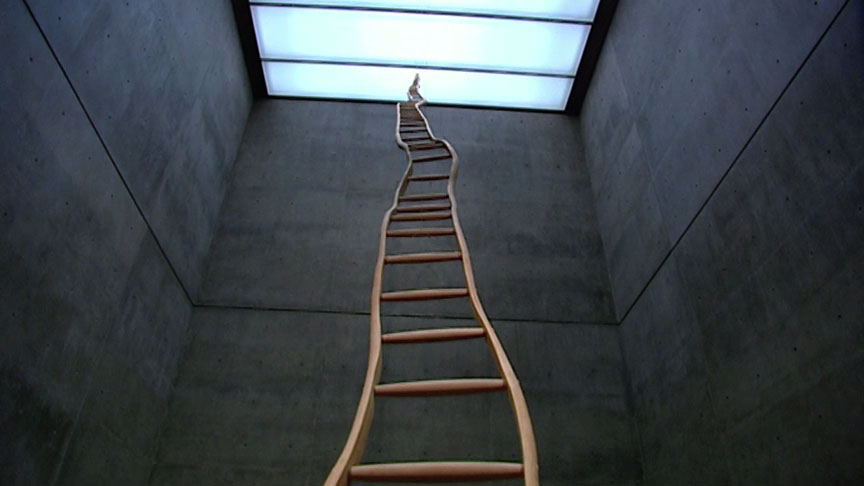

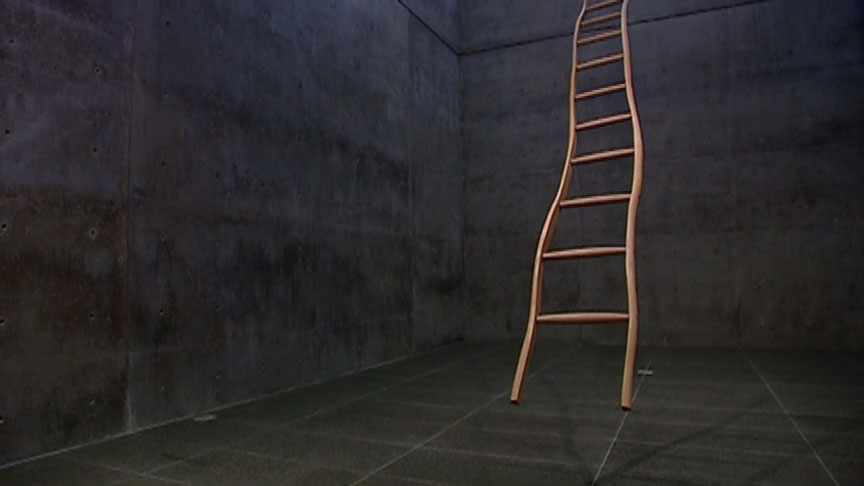

Martin Puryear. Ladder for Booker T. Washington, detail, 1996. Installation view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas. Production still from the "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 2 episode, "Time," 2003. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Artist Martin Puryear discusses his work’s connection to the history of abstraction and the inspiration for his 1996 installation piece, “Ladder for Booker T. Washington.”

ART21: Your work is often talked about as coming out of the history of abstraction. Can you talk about your connection to that history?

PURYEAR: I think the way I work is probably out of step with what a lot of artists are doing in 2003, which is telling stories or conveying specific kinds of information, be it sociological information, psychological information, sexual information—work that is really a vehicle for conveying kinds of information. I came from a generation where the work was itself the information, and so, there remains this belief that the work itself can have an identity that can hopefully speak. Whether it’s through beauty or through ugliness or whatever quality you put into the work, that is what the work can be about.

The work doesn’t have to be a transparent vehicle for you to say things about life today, or what you see people doing to each other, or things like that. Not that that’s not in the work, ever, because I think the work can contain a lot of things. But my vehicle, typically, is to make work that is about the presentation of the work itself and what went into the making of the work as an object. And there’s a story in the making of objects. There’s a narrative in the fabrication of things, which to me is fascinating. Not as fascinating, perhaps, as the final form or the final object itself, but I think by working incrementally, there’s a built-in story in the making of things, which I think can be interesting.

ART21: Do you think abstraction, or the kind of work you are describing, will continue on?

PURYEAR: I think it probably will. Who can tell the future? But I remember a show that must have been in the late ’50s or early ’60s, about realism, at the Museum of Modern Art. And there was an awful lot written about the end of realism, the fact that realism as a way of making art was on its way out. And realism is alive and well today. It has come back and completely transmogrified to do very different kinds of things for the artist than it did in 1960 or 1970, very different kinds of things. But, as a practice, it’s still very much with us. The camera didn’t wipe it out. Abstraction didn’t wipe it out. And I think there are abstract tendencies in art that certainly predate the twentieth century. So, I think that isn’t going to go away.

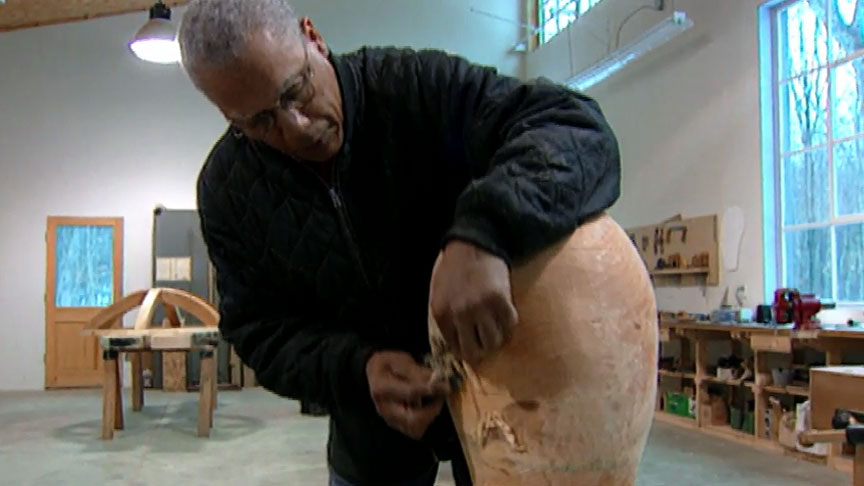

Martin Puryear in his studio, Accord, NY, 2003. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Time,” 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Do you think it’s important to make abstract works today? Is it important to make a case for abstraction in art?

PURYEAR: I think there are different degrees of stridency with each artist, depending upon who they are. And I think, in my case, I’m making a case for my own vision. It’s like breathing. It’s not always the same. And it can change. It can actually move in a direction that has got some representational tendencies, or at least some allusive tendencies. Or some kind of tendencies that are very suggestive. I mean, my work is not minimalist. The kind of abstraction I practice is probably an earlier kind of abstraction, where I’m not committed to simply presenting a form that has to be addressed only on the terms that I say it can be addressed at—which is, I think, what minimalists are. They really were interested in shutting down any other alternative ways of looking at the work, other than to take the work on the terms that they set. It’s a very idealized way to look at work, with very, very, very narrow parameters. And I think, in my work, it feels like it’s got a lot more potential for evolution and change and open-endedness. Which I think feels more resonant with what it is to live a life.

ART21: What’s the genesis for the ladder piece, Ladder for Booker T. Washington? That work is perhaps the most representational piece of yours from the past decade.

PURYEAR: The title came after the work was finished, first of all. I didn’t set out to make a work about Booker T. Washington. The title was very much a second stage in the whole evolution of the work. The work was really about using the sapling, using the tree. And making a work that had a kind of artificial perspective, a forced perspective—an exaggerated perspective that made it appear to recede into space faster than, in fact, it does. That really was what the work was about for me, this kind of artificial perspective. It’s an idea I’ve been wanting to do for a long time. And it requires a certain actual length. It’s a piece that couldn’t have been done small. As it was, it was thirty-six feet long.

I actually had a version of a piece like this that I had conceived to go into a public space in Tokyo, which would have been close to two hundred and fifty feet long. This was extremely exciting to me, because then the work would have been long enough where you could actually wonder whether the perspective that you were looking at was in fact manipulated or whether it was real. And that prospect, to me, was extremely interesting—to be able to make the piece to such an extent, make it long enough, that you would have a confusion as to whether this is the artist’s manipulation of reality or whether this is in fact what is really going on here. It didn’t happen. But anyway, this piece was realized to work with that same idea, the idea of a forced perspective.

Martin Puryear. Ladder for Booker T. Washington, detail, 1996. Installation view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Time,” 2003. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Does it still have some sense of that forced perspective?

PURYEAR: Oh, yes. Anyone looking at it knows that the tip of it is not as far away as the artist is telling you it could be. This is not a new device. It was used in the Renaissance a lot. You see it in garden design, and you see it in trellis design and other artificially diminishing forms in space. But then there was the whole relationship, literally, to ladders. I mean, it is a ladder. It’s made like a ladder; it’s made like country ladders you see, in places. People would cut a tree trunk in half and put rungs between the two halves; and that’s a ladder.

ART21: Is there something about this piece that amuses you?

PURYEAR: Well, I enjoyed doing it. And I certainly enjoy the way it looks at the Modern in Fort Worth. It’s interesting to me—and this is new for me—but the work does contain a history lesson. Because people who see it want to know what it’s about. It’s a curiosity when they see a title as specific as that. It’s been written about a couple of times. In fact, there’s a wall label in the museum that talks about Booker T. Washington more than it talks about the work, which I find interesting. I think there’s a lot going on in the work as a sculpture. But I think the urgency of the historical information about Booker T. Washington is in terms of what the museum thinks the public would want to know, or should know about it and, I think, in this case eclipses what’s going on within the object. I found that kind of interesting.

ART21: As a sculptural form, it’s very unusual.

PURYEAR: For me, it is. I’m not the first person to use a ladder, I’m sure, in sculpture. But I don’t know if it’s unusual or not. This is the first time I’ve ever seen a person make a work like this. It’s the idea of a diminution in space and the manipulation of that perception, which is interesting to me. Certainly as a woodworker, it was an interesting project to work on. It was a challenge to split a tree, a thirty-six foot long tree. That’s part of my pleasure in the making of it, which isn’t what’s left for the viewer to look at. That’s just my end of it, my end of the making of it.

Martin Puryear. Ladder for Booker T. Washington, detail, 1996. Installation view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Time,” 2003. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: So, what do you think is the connection between what’s going on in the work and the title of the piece?

PURYEAR: I mentioned about the perspective being really what the work is about. And the idea of Booker T. Washington, the resonance with his life, and his struggle—the whole notion that his idea of progress for the race was a long slow progression—of, as he said, “putting your buckets down where you are and working with what you’ve got.” And the antithesis was W. E. B. Du Bois, who was a much more radical thinker and who had a much more pro-active way of thinking about racial struggle for equality. And Booker T. Washington was someone who made enormous contacts with people in power and had enormous influence, but he was what you would call a gradualist.

And so, it really is a question of the view from where you start and the end, the goal. This is something I don’t really want to elaborate on too much because I think it’s in the work—the whole notion of where you start, and where you want to get to, and how far away it really is. And if it’s possible to get there, given the circumstances that you’re operating within. The joining of that idea of Booker T. Washington and his notion of progress and the form of that piece—that came after the fact. But when I thought about a title for it, it just seemed absolutely fitting.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.