Interview

Collaborating with Poet Henri Cole

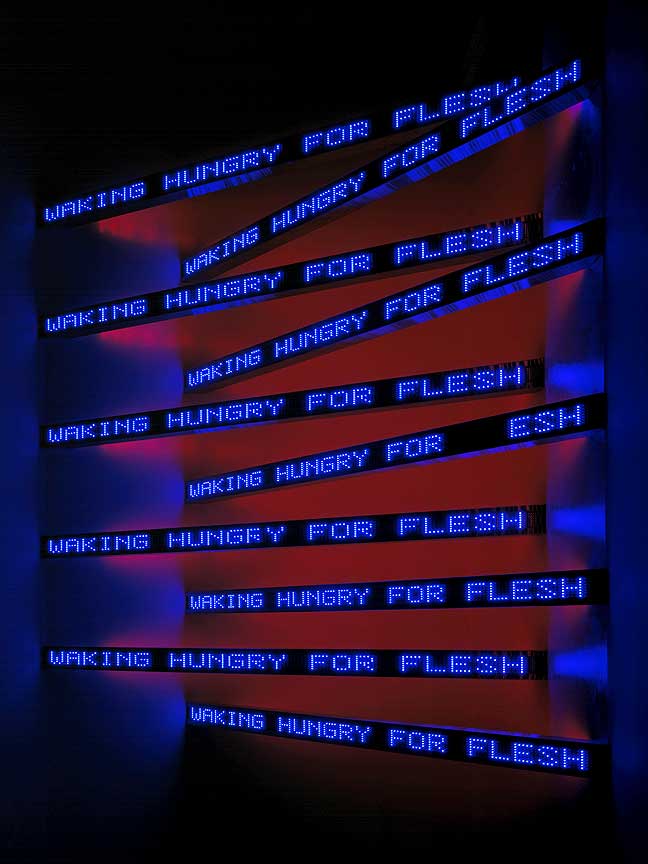

Jenny Holzer. WHITE, 2006. Nichia white LED's mounted on PCB with aluminum housing, 192 1/4 x 216 5/8 x 5 3/8 inches. Installation view: Cheim & Read, New York. © 2007 Jenny Holzer, member Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Artist Jenny Holzer and poet Henri Cole discuss how their collaboration began, and the ways in which their work together has evolved since.

ART21: How did the collaboration between you two start?

COLE: We met in Berlin. We were both fellows. Is that right?

HOLZER: We were fellows, yes…

COLE: …at the American Academy in Berlin. And we lived on the third floor of a great, big, old, rambling house . . . next to each other? Maybe there was a room or two between us. We were living with a bunch of political-scientist types. So, we naturally gravitated towards each other.

HOLZER: There were people there who knew about “Star Wars” [Strategic Defense Initiative] and journalism. And we didn’t, so we had to take walks together and get away.

ART21: You two couldn’t co-opt those scientific types and journalists?

HOLZER: I don’t think they had much use for us. (LAUGHS)

ART21: Talk about the first project you did together.

HOLZER: I was picking your brain because I was trying to write something.

COLE: Oh, that’s right.

HOLZER: Yeah, I was trying to get free advice.

COLE: You were trying to conceive the Neue Nationalgallerie project, to do a gigantic ceiling piece. And I guess you did conceive it while we were all together that year, or those six months. Our conversations about art began at that time.

HOLZER: And we started our practice of gossiping about other people. That was another good academy activity.

COLE: What was the first thing we did? Was it the trees?

HOLZER: Well, the first unofficial thing was at Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgallerie building in Berlin. I kept having you go with me and asking you, “How do you think this would look?” and then bugging you about the text.

It’s a perfect building, and it stymied me for a while. It didn’t need or want any art, and I didn’t want to spoil it in any way. But finally I realized that melting the building might be interesting, so I did that with LED in the ceiling. And, courtesy of the glass walls, the reflections from the LEDs made it seem as if the building was infinite. And the amber color seemed to liquefy the top. I liked this very much.

Jenny Holzer. Purple Cross, 2004. Electronic LED sign. Installation view: Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris. Text: “Blur” from “MIDDLE EARTH” by Henri Cole. Copyright © 2003 by Henri Cole, used by/reprinted with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Photo by Attilio Maranzano, © 2007 Jenny Holzer, member Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

ART21: But what was your first real collaboration?

COLE: I was thinking it was in the forest, where you put the sonnets on the trees. Is that it?

HOLZER: Oh, that’s right, yeah. I forgot about the log project.

COLE: There was a forest in a town in northern Germany. Jenny had carved several sonnets into these ancient fallen trees lying in woods, where dog walkers and park goers drifted through. So, they came upon these sonnets . . .

HOLZER: Not just “these” sonnets; they were yours.

COLE: Were they?

HOLZER: A very odd project—a good start.

COLE: The great thing about it is that it might have disappeared by now. Moths, insects, and worms probably have consumed it.

ART21: And what was next?

HOLZER: Then we moved on to Xenon Projections. Again, I kept picking your brain, trying to find the best poetry for any number of projections in New York, Venice, Paris, all over the place.

COLE: Jenny projected a poem of mine, called “Blur,” in Venice. It’s a sonnet sequence projected on the police headquarters of Venice, which is across from the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. The building was a building of fear to Venetians during the war. And my poem was a very naked love poem. To project that onto this scary building was interesting and meaningful.

HOLZER: Substituting one kind of fear for another one.

ART21: How did it work?

HOLZER: We had two projectors, so the light crossed over the Grand Canal, and we would have the same poem on the Peggy Guggenheim as on the police station. That was pretty nice.

COLE: Very beautiful photographs or stills were made from that projection.

ART21: Do you usually document your work this way?

HOLZER: It was after this that it dawned on me that I should be making some kind of record of these projections that only last for a day or a few hours. We turned the good photography that we had into pigment prints, so something stays.

COLE: Yeah, they’re very beautiful prints, black and white. The projection of the text was actually in blue light; I remember. And there was considerable thought given to what color the light should be, because you have a code of your own for what each color represents. I remember red was fear and blue was more subdued . . .

HOLZER: Wistful.

COLE: Wistful, there you go. I just I remember you had a code; I don’t remember what everything represented.

HOLZER: Well, white’s standard, because it’s lovely and relatively neutral, and it’s the brightest. But when it’s possible, as it was in Venice, I will veer off into the occasional red, because it is desperate, or blue because it’s quiet and sad.

Jenny Holzer. For 7 World Trade, 2006. Electronic LED sign. Installation view: 7 World Trade Center, New York. © 2007 Jenny Holzer, member Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York. “Here is New York” reprinted by permission of Martha, Steve, and John White, copyright © E.B. White 1949, 1976.

ART21: How do the colors affect the overall meaning?

HOLZER: Sometimes the color is there to fight the text, other times to emphasize it. And with the projections, since we’re always shining light on something, the color often mixes with the screen, which is a building, the ocean, or what have you. So, it’s varied, and this is a luxury.

ART21: Say more about the poem.

COLE: This is a poem in six parts, six free-verse sonnets. Each part comes at a relationship from a different angle, so each part is really self-contained. Some parts are more abstract; some are more narrative. The third part of the poem is a more contemplative part that speaks to different ways of being in the world:

“Then everything decanted and modulated as it did in a horse’s eye. And the self, pure, classical, like a figure carved from stone was something broken off again. Two ways of being, one seamless, saturated color. Not a bead of sweat. Pure virtuosity, bolts of it. The other, raw and unsocialized, an opera of impurity like super real sunlight on a bruise. I didn’t want to have to choose, it didn’t matter anymore what was true and what was not, experience was not facts but uncertainty. Experience was not events but feelings which I would overcome.”

HOLZER: This looked good—really blue on the Grand Canal.

COLE: One of the interesting things about seeing the poems projected is that I write poems to be published in books. So, they have punctuation, a shape on the page, and the experience of the book to frame them. But with what Jenny does, they have a different life in her art. They have the punctuation often stripped out of them. They’re re-lineated. And it’s interesting to see how much can be taken out of them and still have this blood running from them. But also, the poem becomes like one voice in a chorus. You have the voice of the words, the voice of the color, and the voice of the architecture. You have the voice of all these different things working together to make art. It’s really a whole different thing than when I’m writing a poem; it has a completely different life.

ART21: Jenny, what’s your relationship to writing?

HOLZER: It’s hard to write, so I don’t do it anymore.

COLE: I think some critics have been mean about your writing, and that makes you silent. I think that’s part of the reason that our collaboration came about. A couple of mean reviewers said cruel things about your writing—you never had any pretense of it being poetry.

HOLZER: It’s been weird. People have said, “Oh, that’s bad poetry,” and I say, “It’s not poetry.” You know, it’s hard to be slammed for something that you’re not doing. The other reason why I’ve quit is that, to address these awful subjects, I tend to enter that state of mind. I think I’ve done it maybe as many times as I can.

COLE: Well, you’ve tried lots of different kinds of writing. There are lots of different settings. There’s the Greek myth, biblical speak, a journalistic voice, and a kind of ironic touching voice. And then you have a kind of brutal, descriptive, violent voice. There are lots of different ways in which you do write, but the writing is just part of the whole. It’s like a screenplay or a text for a play. I feel it’s unfair to consider the writing apart from the framework of the color and the shapes and the setting.

HOLZER: Some of the series were pretty horrible to write, like the Lustmord ones, because I wanted to address the subject in the round. I wrote as the victim, as a relatively neutral, sad observer, and as the perpetrator. Bouncing back and forth between those was not so healthy.

COLE: Can you imagine making art without words?

HOLZER: I’ve done it a few times, and it was a pleasure and a relief. Or done it with very few words, like for Black Garden in Nordhorn: I used black or very dark red plants to show what was wrong in that part of Germany during the Second World War.

COLE: It seems to me that your work has this abstract component: the way we respond to color, walking into a room in which there’s color and motion and materials. But then, there is this ultra-real part of it too—the words—which are always about very primary emotion. There is fear, grief, triumph, and desperation in them. I wonder what it would be like if they didn’t have the words? What kind of art would you make? To me, the words are what make your work distinct.

HOLZER: I’m happiest dealing with the abstract part, the composition and making a complete environment. But I’ve been really delighted to know a little more about poetry because it helps me extend my range. I can deal with subjects and have text that I couldn’t produce. But I can present them in a way that I find suitable and compelling.

COLE: A poem has music and sound and words rubbing together. It’s on the page. It’s black and white. So, in a way, what we do is not so different from each other, though my audience is readers and yours are viewers.

HOLZER: It’s good to get these people together, finally.