Interview

Museums and Collections

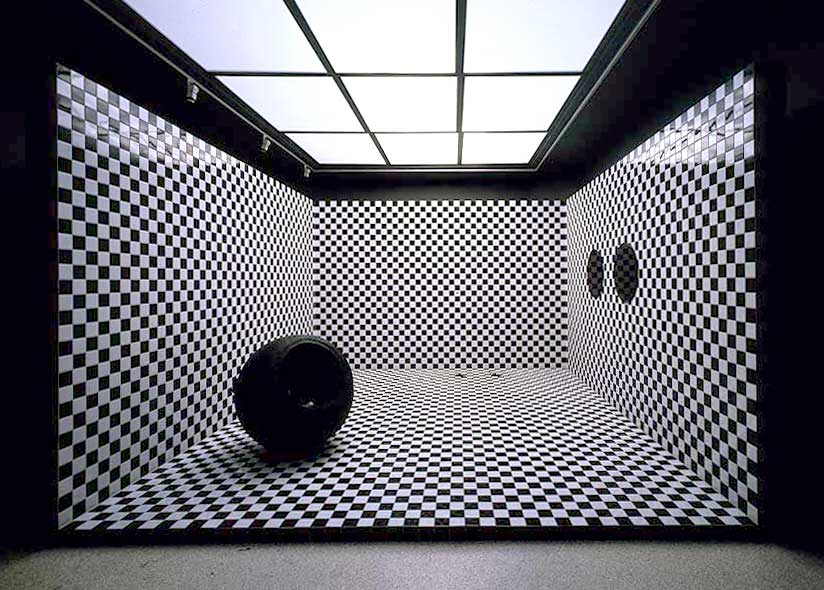

Fred Wilson. Turbulence II, (Speak of Me as I Am), 2003. United States Pavilion 50th Venice Biennale: Dreams and Conflicts. Photo by R. Ransick/A. Cocchi. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York.

Fred Wilson discusses his unusual approach to museum installations, and his experiences working in museums around the world.

ART21: Your museum projects are an unusual kind of art practice.

WILSON: I came to making these museum projects and calling them art not via art history, necessarily—not via seeing Joseph Beuys or others. I came to it via being an artist and working in the museum and gallery world—creating exhibitions and working in museums in various capacities: educator, preparator, museum guard. Coming from my background as an artist, I am seeing museum space as a constructed kind of design space, as an installation environment—very much like an artist, you’re manipulating objects, light, color, spatial relationships. So, I thought perhaps I could manipulate the space, make it kind of a trompe l’oeil of a museum space. Critiquing, as well, the notion of museum.

A lot of times, people just think I’m a curator. But in fact, the things I’m creating are much more about a meta-narrative than about museums and displays. The subject of the exhibition—which is what most curators are concerned about—takes a back seat to that. I’m just using the museum as my palette, basically.

When you go into one of my projects, a lot of times you’re scratching your head. You’re scratching your head because the information—like any artwork—makes you question your own thoughts and have to work a little bit. It’s not telling you everything. Your emotions and your feelings about what you’re seeing and your experience are as important as any specific information that I’m giving you. So, it’s a very different experience when you’re in one of my projects. And it’s even a greater experience if you didn’t know that I did it, because then you’re just having this experience without knowing that it’s an artist who created it for you.

ART21: How do these projects come about?

WILSON: I never contact museums to do a project. They have to want me there, because what I do is so different from what a normal curator would do. Often it’s about the institution, and one never knows what I’m going to bring up. So, they have to really want me there. Usually the director or the chief curator invites me. With Sweden, the director invited me to do a project there. They don’t usually ask me to do something specific. I’m invited to look at their collection and create a work from their collection. I can basically have free rein to do what I want to do. And thankfully, people know what I do now in many, many corners of the globe, so I have wonderful opportunities to do projects with different kinds of museums. And I’m always looking for a very different collection, a different place, because that really inspires me to do something completely different from what I’ve done before.

Fred Wilson. Chandelier Mori, (Speak of Me as I Am), 2003. United States Pavilion, 50th Venice Biennale: Dreams and Conflicts. Photo byR. Ransick/A. Cocchi. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York.

ART21: Say more about your installation at the Museum of World Culture in Sweden.

WILSON: I started the way I normally start: meet everyone, look at the collection, talk to people about the collection, research the collection, and then try to understand the city I’m in and make a piece. This museum had a very old history, but it ended: there was no building. They were building a new building, but everyone on the staff was pretty new, and certainly none of them had been around when the things were collected. So, it was an unusual experience, in that there no was memory within the walls, even; no, this was a new place. The collection’s old, so I did a great deal of research on the collection and the archaeologists and anthropologists who collected the things.

I really start these kinds of museum projects without knowing what I’m going to do. I try to just go in, tabula rasa, and be a sponge. I always have a little notebook about each project and write down everything—every experience, every thought, anything that was important along the way. In the beginning it’s fun, and then as you keep going, you get a little nervous because you have to figure out what this is, and you only have a certain amount of time to get this piece done. So, it gets a little nerve-wracking. But it always comes together. If I trust the process and have enough time, all the strands come together.

Looking through all this stuff, I became interested in the archaeological things. They have huge African, Indonesian, and Latin American collections. There were going to be other exhibitions of African art in the museum, so a lot of the collection—the good stuff—was being used already. I looked at the Latin American collection and became really interested in what they had. And they had both ethnographic and archaeological things. They had many, many, many things; and the things had been around for a long time.

Personally, one issue that came up, for me, was with the ethnographic collections. I felt really uncomfortable using much of the ethnographic collections, not necessarily because how they were collected. I didn’t know necessarily how they were collected. I knew some issues, but not the subtlety of it. I usually like to talk to the people whose things I put on view. Usually I’m using things in a museum that are from that culture, but here I was in Sweden, looking at native things from Latin America. There was nobody to talk to about these things and no way to understand—on any level—how people felt about these things or how they related in the context of the culture.

A western art museum is something I’m familiar with; that’s one level of understanding that I already have. Working in the Historical Society in Baltimore, it was important for me to understand Baltimore a bit—at least absorb people’s feelings about their world—in order for me to make a piece that fit within that place. I never think specifically how it fits, but just something about being in a place with people from a place—you become more a part of that place and less an outsider, less someone who would create something that would not make sense for that location. And that, to me, is really important because that’s who’s going to see it, generally.

With this collection, this was not the case. These ethnographers from Sweden brought things in, and so I had no sense of the context of these things. It was just me and these objects, and I felt very uncomfortable. Part of the problem with ethnographic museums, in general, is that these things are put on view without the culture or the people who made them. There’s very little sensitivity around that, and I didn’t want to be a part of that. So, I really avoid ethnographic collections.

Archaeological collections I found I could work with a little more. The communities were no longer the same in contemporary times as they were a thousand years ago, so I felt that I could work with those materials, because there wasn’t really a community to talk to about them. I could lay over whatever I thought about them as much as anyone else.

But what really got to me was that I was going through these ethnographic collections—particularly I was looking through ceramics—and they had all these stones. The hysterical thing about this was I really didn’t think I was going to use stone, the first few days I was there. I had this film crew coming, following me around, and I knew they wanted me to pull out something and say, “Yes, I’m going to use this,” for the cameras. I didn’t know what I was going to use, but I thought, “Well, I’m not going to use stone, so I will just go and look at the stones.” And so, I went over to the stones to pull out a stone just to say, “Yes, this is really interesting to me.” I didn’t want to say that I was going to use it or not use it, but I thought, “Well, this is something I probably won’t use, so I’m safe to have some vague interest in it.”

The thing I found was something from my family’s island. The Carib Indians, of which my family is a part, had these ancient stones from islands in the Caribbean the size of a volcano. These stones were taken by so-called archaeologists in the 1700s or early 1800s. And here they were. I’d never seen anything like that before. So, this thing I thought I would not use at all became the center point for how I thought about looking at the collection—the idea that these ancient stones have no provenance. There’s no way to know where it came from on the island, what it was used for, where it had been—they were just in the collection, in the basement. They would never be displayed, ever; they would just sit down there.

And here I was, seeing this thing that relates to my family. There’s very little to be seen of the Caribs. Columbus came to my family’s island in 1498, and everybody knows the story of what happened with Columbus and then the colonialists. And then, here these stones are in a basement in a museum in Sweden. They would just sit there, and nobody would ever know that they were there. So, I thought, “How much of the world is moving around like this, where people have no idea where their cultures or the things that might relate to them have ended up?”

Fred Wilson. Untitled, 2005. 1 table with 47 milk glass elements, 1 plaster bust, 1 plaster head, 1 standing woman and a ceramic cookie jar; 77 3/4 × 92 × 43 7/8 inches. Photo by Kerry Ryan McFate. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York.

ART21: It’s often said that movement, especially global travel, is a very modern thing.

WILSON: But it’s been happening forever, for various reasons. For positive and sometimes not such positive reasons. I just thought it was interesting. I began to think that it’s a lot about why things move around in the world, and how the museum is in the center of all of that. So, the exhibition title is Site Unseen: Dwellings of the Demons. And I view the “site unseen” as the literal things that are never seen before by the public, but also these invisible processes of museums as things that are unseen.

ART21: Do you often confront radically different processes in museums around the world?

WILSON: There is an international way of working in museums. I’ll come to a museum and say, “I want to do this,” and they won’t allow me to move anything around. They all do that. (LAUGHS)

But, pretty much if I’m there long enough, they give me the white gloves, and I can start to move things. Sometimes they have museum designers. I decide on paper how I want it designed, but then these designers come in, and it all goes up by itself. The museum comes and does it. And sometimes I’m the only exhibition that’s happening at that moment, and so everything’s focused on me. And so, I have this crowd of people doing what I want them to do. And sometimes I have absolute silence and am able to concentrate. Sometimes there are a lot of meetings with different museum people; and sometimes there’s no meetings, and I’m able to do what I want to do, freely, and I have only a few people to work with. It tends to be very different.

Since this is a brand new museum, everything is happening at the same time. Everyone is trying to get things ready. The museum itself, the building, is being made ready as well. So, there’s a lot activity here. Probably more than I’ve experienced because it’s the grand opening of the museum. I thought I should mention that because it is such a different experience.

In the United States, certain things are allowed, and certain things are not allowed. I can move certain objects, and I can’t move other objects. I was in Holland and did a project where they brought out these Vincent Van Gogh paintings, and I was able to hang them myself. And of course, a Van Gogh painting in the United States—I would never get anywhere near it! But in Rotterdam, they’ve got so many of them!

So, in different museums, I have different experiences. With American Indian objects, some things you can see and work with, and other things you can’t even see. They’re closed in a room because they’re sacred objects. Or they’re secret objects that only certain members of the tribe can view, the chief or the religious person. You can’t even go in the room. There are many protocols concerning exhibiting objects in the same room when working with American Indian objects. So, each environment is very different, and that’s of course what makes it interesting for me, being in new places: different cultures, different people, different collections. I never have any problem with being inspired. There’s always something new for me to be inspired by.