Interview

Myths, metaphors, and more

Eleanor Antin. The Death of Petronius from The Last Days of Pompeii, 2001. Chromogenic print; 46 5/8 x 94 5/8 inches. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Artist Eleanor Antin speaks with Art21 Senior Education Advisor Joe Fusaro in a series of lively and engaging emails that covered her thoughts on preparing for exhibitions, working with allegories, making “controversial” or “risky” art, teaching art, and working with actors (vs. models).

This interview was originally published in the Art21 Magazine (Part 1; Part 2).

Fusaro: When you share a series of work or create a proposal for an exhibit, what are some things you think about going into the process?

Antin: Historical Takes at the San Diego Museum of Art was a mini retrospective of the work I’ve been doing over the last eight years. Earlier, I had a full retrospective from the late 60’s through 1999 at LACMA and I traveled with that huge show to several museums, including St. Louis and the UK while wondering, ‘where the hell do I go from here?’ Somewhere around that time, one sunny afternoon, I was driving down the mesa to La Jolla, the ocean sparkling blue green below me, La Jolla gleaming in the bay, when suddenly I had an apperçu that hit me with a strange sad power. La Jolla was Pompeii, rich and gleaming, without a clue that it was on the verge of annihilation. Pompeii was where the rich and powerful had gone to escape the heat, stink, and mosquitoes of the Roman summers, where those senators fortunate enough to live that long in the notoriously insecure world of imperial Rome went to retire. Extend the metaphor, and you have the ancient empire merging with ours, where affluent citizens lived the good life innocent of the destruction lurking just around the corner.

So since then, I’ve been working with myths, metaphors, characters, and settings invented out of the ancient world of classical Greece and Rome, all the time aware that these are really my neighbors. Maybe we don’t have a volcano on our doorstep, but with global warming, climate freakiness, wild fires, water loss, disease migrations, economic destabilization, terrorist vengeance—hey, we’re on a roll here…

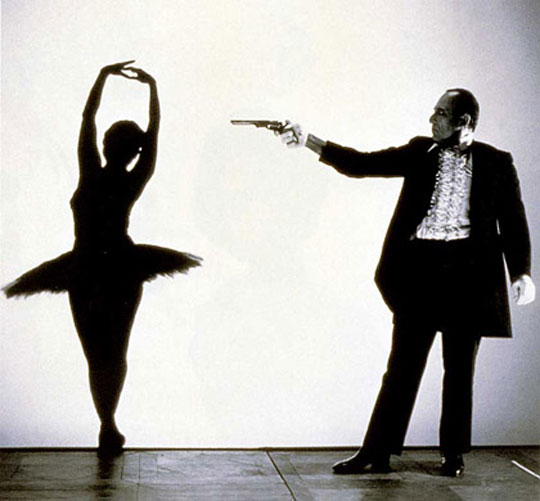

Eleanor Antin. Love’s Shadow, 1985. 16mm film, black-and-white; 2 1/2 minutes. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

For me a show is always motivated by a generative metaphor, a kind of poetic image which opens up to related ideas, images, ambiguities, dreams, sensations. Nothing is closed, there is no end. If the viewer wants to keep looking and has a playful mind, my work can be like a hall of mirrors, expanding and suggesting new meanings which, in turn, may suggest others. Poussin and Magritte are among my favorite artists. They may have different sensibilities but their works are always restless and fluid. Unfortunately, I find the art world too ready to summarize and simplify. I’m often embarrassed by the simplistic takes even well-meaning critics may have on my work. I become a couple of declarative sentences in a stranger’s mouth.

Fusaro: Why do you think some people consider your work controversial? How do you respond to this reaction?

Antin: I’m confused when people consider my work “controversial.” Or the word most often used is “brave.” I don’t know what they mean. This isn’t Soviet Russia or Hitler’s Germany—yet. Those countries may have been intellectually monstrous and physically murderous but they seemed to think artists were important enough to persecute. Here, relatively few people care what artists do. This allows us freedom even if it assures us of irrelevance. So to call me brave is silly.

A well-known curator once said disapprovingly to me, “you always do whatever you want to do.” What should I do? What he wanted to do? You can say the art world cares what we artists do. But who are they, this art world? Dealers? Curators? Critics? Collectors? Other artists? Fellow travelers? I’ve been with a great dealer, Ronald Feldman, since 1977 and he respects artists and assumes we will do whatever we want to do. Curators come and go. Critics have deadlines and space constraints. Collectors? Oh, please! They don’t know what they want until somebody tells them. Hopefully they have intelligent advisors, but they often don’t. Other artists, yes, they’re the best part of the art world, though many of them seem to feel that there’s a war out there, so they’re often in survival mode. They won’t always tell you how much your work means to them and that can make you unhappy, or even sometimes buggy, but hell, if they get ideas from you and you stimulate or provoke their work, isn’t that a good thing after all? It just means that there’ll be more good art around.

Eleanor Antin. The Angel of Mercy, 1977. In the Trenched of Sebastopol from My Tour of Duty in the Crimea. One of 38 tinted gelatin-silver prints, mounted on handmade paper with text; 30 × 22 inches. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Fusaro: The San Diego Museum of Art describes your work as “affectionate spoofs on classical culture with metaphorical parallels to the excesses of contemporary consumer economy.” Is “affectionate” a word you would use to describe the latest work and if so, how is it “affectionate”?

Antin: I don’t do spoofs and if I’m feeling affectionate, I’ll adopt a puppy.

Fusaro: Fair enough…I had a feeling. You mentioned the drive to La Jolla being powerful and influencing your work. Is this a way you’re often inspired—through driving, trips, and time to reflect on your own? Or was this atypical in terms of the way you often get ideas?

Antin: Somehow, by the time I finish a project, there’s always a new one waiting just around the corner. Since my works are always projects with numerous parts, they usually take several years for me to play out their implications. Sometimes I feel like I’m peeling away the layers of an onion, at other times I’m opening up a peapod.

For instance, back in the 70’s when I began working with different personas (a king, a ballerina) and I was ready to take on a nurse persona, I remember walking through Brooklyn Heights past a nurse’s dormitory with large stuffed animals in many of the windows. Teddies, tigers, whatever. Wow! These were grown women studying to become nurses and they were still kids at heart. Those cuddly creatures, endearing and kind of dumb, reminded me of when I was a kid. I used to run home from school every day to play with my paper dolls in an ongoing soap opera of love, murder (I was especially fond of stabbings with pencil points), theft (like one of the ugly dolls stealing the excessive and glamorous clothes of a richer, prettier doll), illness, death (the corpse was buried in an earth-filled cheese box that stood for years on the windowsill of my room). Unless, that doll was found guilty of murder and was executed by being torn into pieces and flushed down the toilet. It was an ongoing saga that continued from day to day in a kind of desperate attempt to represent actual experienced time in the equally desperate, improvised manner of the soaps.

So that was the kind of nurse I would be and I made paper dolls to act out romances and disasters on video (The Adventures of a Nurse, The Nurse and the Hijackers). Then, I was about to do Dug-out Nurse, in which the little nurse becomes manager of a losing baseball team and is treated badly by the macho players until she brings them around and gets them to win the pennant, when I realized, ‘Hey, this loveable little bimbo isn’t the true story of nurses, except in the pornographic pop culture fantasies of the times. What about the founder of nursing as a profession for women, the great heroine of the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale?’ So I made larger, life scale, masonite “puppets” to enact the performance and videotape sections of my huge photographic project about caregiving, war, and capitalism, The Angel of Mercy. All because I happened to take a walk one day down a quiet urban side street.

Eleanor Antin. Judgement of Paris (after Rubens) — Light Helen, 2007. From the series Helen’s Odyssey. Chromogenic print; 38 × 73 inches. Edition of 5. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. © Eleanor Antin.

Fusaro: One thing that has been important in my own work with students and colleagues is related to your suggestion about the viewer continuing to look with a playful mind, continuing to search for new meaning and relationships. How do you suggest people slow down and go about doing this in a shopping mall culture, especially with so much access to an art world that summarizes and simplifies?

Antin: I hate malls. I hate shopping. When I find an artwork that interests me in a gallery or museum, I can sit with it for a long time, letting its possibilities open up to me. The problem is everybody else. My classical Greek and Roman works are allegories, and while allegories were obviously pleasurable and interesting to a medieval or renaissance audience, they’re not the way busy Americans in that hypothetical mall tend to see the world. But I have some tricks up my sleeve. My images are often funny. They can be beautiful. Some are haunting because they’re melancholy as well. Yet where do these emotional undertones come from? Why is that big strong man sitting in front of an old suitcase filled with heavy rocks? We’ve seen him carrying suitcases before. Is that what he carries around?? Rocks? Why? What does that mean? And why is that woman lying on a funeral bier with moonlight spilling down on her while a blonde adolescent girl awkwardly, perhaps fearfully, stoops to catch a ball that any second now, will be thrown by an older man with a demented grin? We’ve seen him before too, with the dead woman, though she was very much alive then.

Each image is its own allegory and since the characters reappear, we recognize them, we know something about them, so they are part of a meta allegory that hopefully is interesting enough to stop the people in that hypothetical mall and even against their will (after all, they probably want to get back to the car before they’re caught in traffic), force them to stop and really look. Because they’re curious. Maybe they’re disturbed. Maybe they’re laughing. Beautiful and sensual and comic images can seduce even self-absorbed people into entering the artist’s world and maybe recognizing something about their own. Or maybe it’s simply that my work possesses what the great anthropologist Malinowski would have referred to as a high coefficient of weirdness.

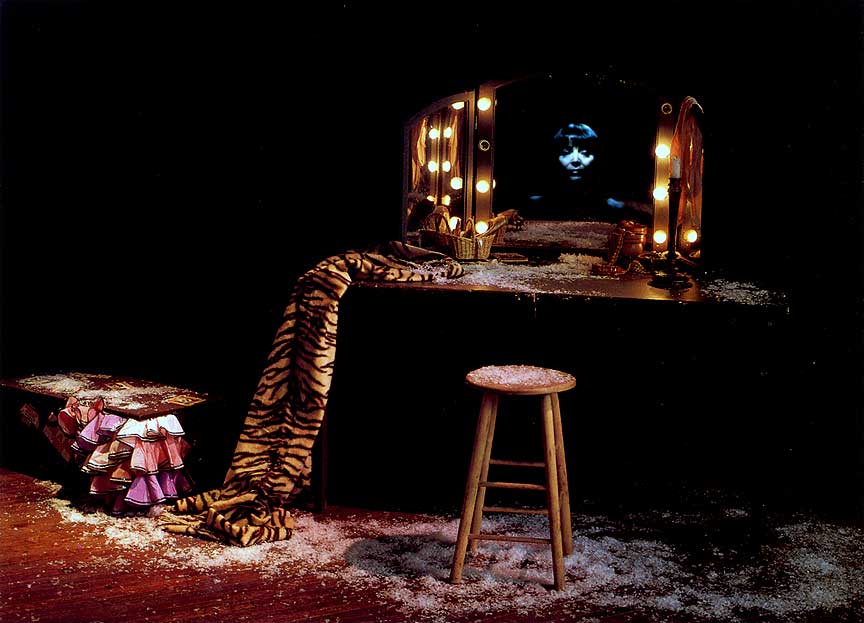

Eleanor Antin. Portrait of Antinova, 1986. Filmic installation; dimensions variable. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Fusaro: You mention having “tricks up your sleeve” to get viewers to look closely at the images you create. I would think that part of it involves taking a variety of risks. Is risk-taking important in order to make these pictures funny, haunting, beautiful, or melancholy? How do you go about taking risks in your work? Is it conscious, or do opportunities present themselves and you go with it?

Antin: For some reason I don’t really comprehend, people think my work is very risky as if I’m walking on a high wire, while as far as I’m concerned, I’m just walking over a crack in the pavement. Some people find my concentrated indifference to the fit of my work with the scene a dangerous game. And I do make some effort to have relevance to the going scene; after all, I’m not a hermit, I know what’s going on in the world. But the scene is often trivial and it’s always transient. I’ve watched a lot of scenes come and go—remember I’ve been around a while and seen artists waste a lot of time on work that 4 or 5 years later has become little more than the emperor’s clothes in the fairy tale. Art is too important to come off of a fashion designer’s runway.

Fusaro: Students often have difficulty when they first work with models/actors. There is something about developing a relationship between the artist and the model to get at truly beautiful (or unique, or shocking) works of art. In the Art:21 series, artists like Sally Mann and Oliver Herring have talked about working with models and how they go about their work. How do you go about your work with actors before a shoot? Are there things that you do beforehand that make the actors more comfortable and able to visualize what you want and what will happen?

Antin: I never have any trouble getting my actors to relax. They are all relaxed. They are either professional artist’s models, actors, and when an occasional plumber or cabbie gets into the act, he goes with the flow. I have stopped interesting looking people in the street, asking them if they’d like to be an ancient Roman or even, if they look cool, a dead Trojan. It turns out that everybody wants to be an ancient Roman. When my actors walk dressed and made up into the set, they’re already in character. Sure, some people are better actors than others but the pleasure and excitement of transcending their every day Southern California environment takes over. And with the few people who suddenly feel clumsy and misplaced, I jump into rescue mode. I charm them, I caress them, I flatter them, I love them, and I show it.

You know, I was a professor at UCSD for almost 30 years. I mostly taught performance, video, personal narrative, grad seminars….but I still loved to draw and at one point, I began to teach a course in Life Drawing, though our conceptual art department didn’t want to spend money for models. This was the 70’s when people were into self-understanding and personal growth, so I said, “Ok guys, we’ll model for ourselves.” Those who felt brave could take off their clothes during their poses, the others were welcome to pose with clothes. Some kids said they’d never take off their clothes. They were shocked. One visiting student from Africa would die first. “No problem, sweetie, just sit here and read a book and we’ll draw you.” But the kids who posed nude, I gave them a loving analysis of their bodies, its language, its elegance, what it said about them. By the end of the term, everybody, including our visitor from Africa, demanded to pose nude. They all wanted to learn about their bodies, because they would learn about themselves. They knew that I wouldn’t lie but that I saw things nobody else did. And I’m the kind of person for whom the cup is always half full, so when I didn’t have beauty to deal with, I certainly could find character, impulse, clarity, expressiveness. And it was always there, of course. As they knew, I wouldn’t lie.

It’s the same now with my actors (and I always call them actors, because ‘model’ is a static word—it implies a certain limpness of action and character. Actors are active artists). Of course, I position them the precise way I want them to be before the camera. I give them their story characters, their relationships. But they always add something of their own. With only 1 or 2 exceptions, I’m very good at casting. With photography, that’s half the job. In a moving picture, a film or video, the actor has a chance to add to his or her affect, to build a character in time and with action. But in a still image, there’s just a fraction of a second. So a large part of the job is to choose the actors to fit visually with my complex allegorical images. Many of my actors have told me that working with me changed their lives. I don’t think it was me; it was the chance to shed their own skin, to work themselves into another time and place without fear or danger and then safely return.

Eleanor Antin. Casting Call, 2007. From the series Helen’s Odyssey. Chromogenic print; 61 × 79 3/4 inches. Edition of 5. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. © Eleanor Antin.

Fusaro: I love the teaching story from UCSD. How has your work as an artist been influenced by your time teaching and how is/was your teaching influenced by your work as an artist?

Antin: I think I was a good teacher because I always thought of it as a kind of cooperative artmaking. My intention as a teacher was not to teach any rules or “right ways”—there aren’t any. I tried to locate within their young work an impulse towards some kind of meaning, a direction toward which it tended, and then worked with them to help them realize it. If we were successful, they released, discovered, and invented their own voice. In that way, my teaching over 30 years has afforded me the intense pleasure of experiencing the making of many kinds of artworks that I myself would never have made.

Fusaro: What was one of your greatest challenges as a teacher?

Antin: Usually the students who took my classes had a more conceptual bent. And unlike life, I put no limits on what they wanted to do or say. Though perhaps there was one kind of limit. I remember the time I stopped an artwork and for me, that’s one of the 8 deadly sins, censoring an artwork. I had asked the students to make a criminal artwork, to do a crime, as it were, but not to hurt themselves or anybody else. One kid brought in a thriving rubber plant and as we watched, proceeded to carefully paint each of its full leaves with black paint. It was shocking. It was also one of the strongest works in the class. We were witnessing what you might call a little murder. He was killing the plant, making it powerless to breathe. It was wrenching to watch, and after a couple of leaves were painted over, I stopped him. I congratulated him on an especially powerful and elegant art work but I couldn’t allow it to go on. We discussed why and what each of our actions, his and mine, meant.

Fusaro: Last question…. Do YOU have any questions?

Antin: No questions, Joe. Yours have opened up some interesting discourse, some interesting memories, too. I don’t always answer in standard Q&A fashion, but then, as they say, I don’t make art in standard ways, either.