Interview

Learning by Looking—Witches, Catholicism, and Buddhist Art

Kiki Smith. Peabody (Animal Drawings), 1996. Ink on paper. Installation view, Landscape, at the Huntington Gallery, Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, 1996. Photo by Gregory Heins. Courtesy of the artist.

Kiki Smith discusses how different spiritual elements and belief systems make their way into her work.

ART21: You seem to have a very interesting approach to process, of letting a work evolve at its own speed.

SMITH: It’s sort of nice—making something, and then nothing comes immediately. That’s how it is a lot of times. You make something, and nothing happens with it for years, and then all of a sudden it can happen. That’s nice. That’s great.

I think the thing about making things is that you have a proof. You have some proof every day that something has been accomplished, that something’s different. If you can make something as that proof, it has a lot of power. You have a lot of power if you can just take your energy . . . But, you know, I’m also happy if somebody else comes and does something on the house to fix it up. I think, “Well, something happened today.”

I realize that I’m very attached to needing a proof of something, a proof that there has been a change. Not just to think about it in my mind, but to have a physical manifestation of that change. It’s like accumulating things. You know, it’s kind of nutty. I’ll go out, and I notice always: when I go out, I come home with things. I try to curb it, the tendency. But I think it’s okay today, because something came in the mail. That was like some proof of my accomplishment.

ART21: A mark of your existence in this world?

SMITH: Yes, it really is. It’s a physical proof that everything’s okay for a minute.

ART21: Does that has something to do with being raised Catholic?

SMITH: It’s one of my loose theories that Catholicism and art have gone well together because both believe in the physical manifestation of the spiritual world—that it’s through the physical world that you have spiritual life—that you have to be here physically in a body. You have all this interaction with objects, with rosaries and medals. It believes in the physical world. It’s a thing culture.

It’s also about storytelling, in that sense, about reiterating over and over and over again these mythological stories, about saints and other deities that can come and intervene for you on your behalf. All the saints have attributes that are attached to them, and you recognize them through their iconography. And it’s about transcendence and transmigration—something moving always from one state to another.

And art is in a sense like a proof: it’s something that moves from your insides into the physical world, and at the same time it’s just a representation of your insides. It doesn’t rob you of your insides, and it’s always different, but in a different form from your spirit.

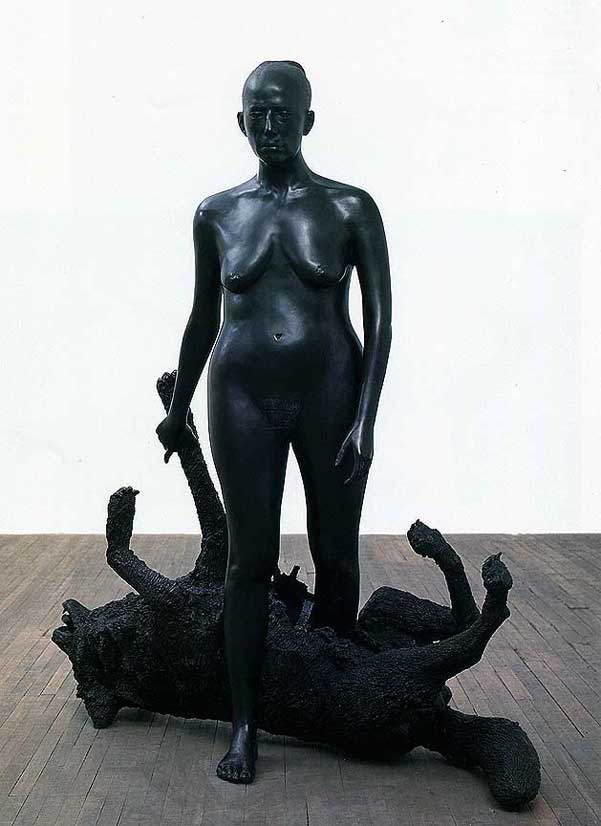

Kiki Smith. Rapture, 2001. Bronze; 67 1/4 × 62 × 26 1/2 inches. Edition of 3. Photo by Ellen Page Wilson. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York.

ART21: Have you read a lot in that area?

SMITH: I read a little bit.

ART21: Information that floats into your consciousness comes from wandering around the world . . . or how?

SMITH: When I was in school, I was a very poor reader. It was very difficult for me to learn how to read. And so, I just had to learn from looking at things. So, I pay a lot of attention to things, or I listen to things, or I listen to what people say. I like Bob Dylan’s line, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows,” because he’s talking in a specific cultural connotation. But it’s true: you have to live to know what is happening in your neighborhood and in your realm of consciousness.

What you’re thinking isn’t particularly unique to what other people are thinking. That’s why you can recognize things from two thousand years ago, because it’s not radically different. How you’re thinking about them might have slight variations, but basically everybody has a body, and they experience them very differently. But physiologically there are certain things happening, and so, it’s no wonder that people think about lots of the same things.

I like learning through observation. I’m very stubborn in it, too. It gets in my way a lot, because I won’t believe things. I won’t believe lots of things that people tell me, until I can see it myself somehow. But being observant is a good way to learn about things. And once you do know about one thing physically, at a certain point it’s easy to translate it then into other mediums and quickly understand it. Like, if you have enough information in your body from doing something, you can then move it around. Like, I can sew well if I need to, or I can do ceramics. I can do different things just from having enough physical experience.

ART21: Let’s talk about the women on the pyres.

SMITH: The women—I put them together because they have a physical relationship to one another. The women on pyres came from a photograph I bought, in an anonymous collection of photographs, from someone’s notebook in the late 1890s from Lyon. And it’s like early collage work from Victorian times, when people started having access to cameras and started making these collages. And this person made these incredibly wonderful collages—chopping this woman’s head off and then her decapitated head sort of rolling around. And then he also made these wonderful ones—of a woman kneeling on a pillow—and then he collages that with a pyre, these women on pyres.

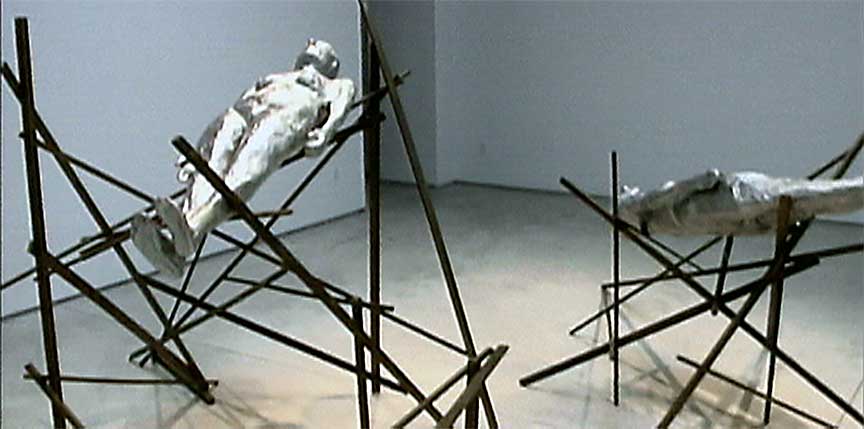

And I was asked to be in a competition last year, or two years ago, for an outdoor sculpture. And I spent a lot of time trying to do it, but I wasn’t good at doing it. And I decided that I didn’t want to make public sculpture that was of other people’s agendas. I couldn’t do that. I can only do things that come from my necessity. And so, then I thought I wanted to make these women on pyres, like these commemoratives for witches. I was making, at the time, drawings of drowned witches, of them floating with their hair in the water. And I thought these women on pyres—that I wanted to make these sculptures and that they should be in all these towns in Europe, like, in each town.

There aren’t commemorative sculptures for witches in Europe. There was a tremendous amount of killing, and there’s little commemoration of that. And so, no one has needed it in their town yet. (LAUGHS) But you know, I just make them anyway. Their arms are out, like Christ saying, “Why have you forsaken me?” I had originally made some, where the pyres were out of metal, but then I just bought wood for it.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: And the bodhisattva figures you’ve been collecting . . . is there a story behind those?

SMITH: I like Guanyin because she is a bodhisattva of compassion. And compassion is something that we’re supposed to think about a lot, in our daily lives. There are relationships between her and the Virgin Mary, in her iconography. The religions are all influencing one another. So, there are times when she starts showing up with a child or being, like, the benevolent mother; they say this is influenced by the Virgin Mary.

I’m a big Virgin Mary fan. I was raised Catholic. Lots of my work refers to the Virgin Mary, and I’ve made a lot of pieces kind of manipulating her around different ways, from my own perverse interests. Guanyin is a similar character, in that she represents this open compassion that envelops you, but then also that you can look at as a model for your behavior in the world. Besides all that, I really like the representation of her and the scale of the house or altar sculpture.

Church sculpture is something that’s very influential to me. It has lots of decorative elements. It has the serene faces, where they’re looking down on you always. There are interesting things about the proportions. Often the heads are much larger than the bodies, which is something I’m always interested in. Gauguin made great sculptures. I guess you’ve seen Tahitian models for figurative sculptures, where the head is about three times the size of the rest of the body. And if you think about it, Alice from Alice in Wonderland has that, where the head’s very enlarged. In lots of the Guanyins, the heads are much larger than the bodies, proportionately.

The Guanyins tell me to pay attention. That’s my new excuse for everything; it tells me to pay attention, and I just do. They say, “Pierce me with your eyes.” I went and saw one the other day, and then it said, “Pierce me with your eyes.” I like that because you’re not sure whether it’s telling you to look at it or you’re telling it to look at you. Like darshan, like being blessed. Like wanting a blessing in Catholic church: you go touch the feet of the saint or something because you want a blessing from them. It’s important to stay in the gaze of what’s important to be thinking about.