Interview

The Melodrama of Gone with the Wind

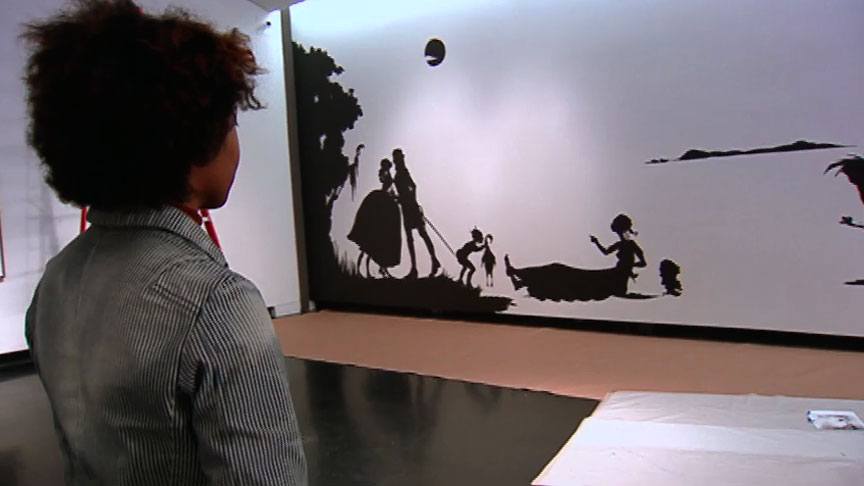

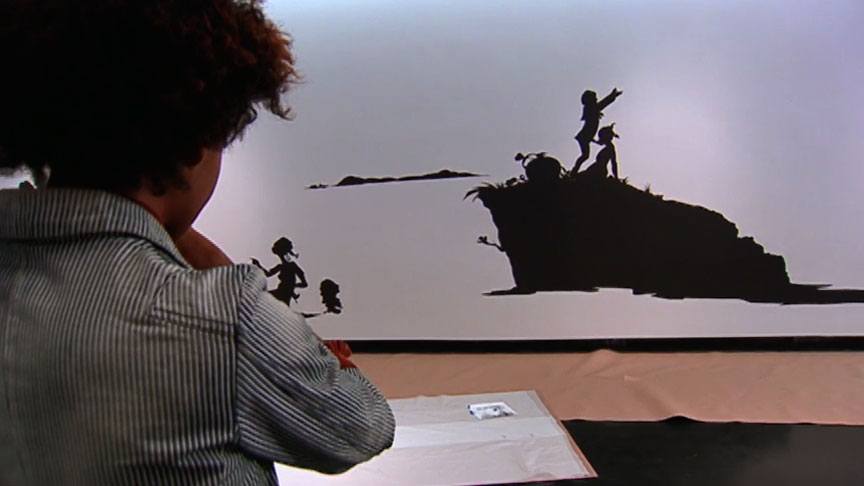

Kara Walker installs Gone, An Historical of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994) at the Tang Museum, Saratoga Springs, NY, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Kara Walker talks about her interpretation of Gone with the Wind, and how it inspired her first silhouette piece, Gone, An Historical Romance of Civil War As it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of Young Negress and Her Heart.

ART21: Your very first silhouette work, Gone, An Historical Romance of Civil War As it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of Young Negress and Her Heart, makes reference to Margaret Mitchell’s novel, Gone with the Wind. What influence did this novel play in the development of your work?

WALKER: Gone with the Wind was one of those books that I already had preconceived ideas about: I already knew that I wasn’t going to like it. (LAUGHS) And some of my experiences in Atlanta with the mythology of Gone with the Wind included things like the sequel to it that came out around the time I was working in a large bookstore. And some of the more personal and private events that happened in and around places like the Cyclorama, which is not too far away from where they filmed parts of Gone with the Wind, and where the fake Tara was.

I had built up prejudices against Gone with the Wind. The first time I thought I would work with it, I was in graduate school, and I was making a collage on top of the book, Gone with the Wind, but really, without having read it. I decided that wasn’t going to work, about halfway through.

And so, I plopped down, started to read the book, and was thrilled with how engrossing that story was, and how grotesque it was at the same time. My interests were already running along the lines of other versions of the historical romance—the permutations of Gone with Wind, to some extent. It was the most fitting choice of text to work with. But the romance of it, the storytelling—it was so rich and epic, and that was what I hadn’t expected. I hadn’t expected to be titillated in the way that stories like that are meant to titillate. And, at the same time, it was so much fodder for the work that I wanted to do.

ART21: In some ways, that kind of storytelling is like the silhouette itself: evasive, yet confrontational.

WALKER: The silhouette lends itself to avoidance of the subject—of not being able to look at it directly—yet there it is, all the time, staring you in the face. There it is, the whole world of Gone with the Wind and its legacy and the way that affects people’s everyday encounters. I went through my young adult life in Atlanta half-blind, let’s say, ignorant to some extent, because there it was. I was actually blinded by this melodrama. And the melodrama includes a kind of soft-focus view of racism and laws that are passed and were passed, and continue to be shifted to affect some kind of change, or to affect some kind of—oh, I don’t know how to describe it exactly . . .

You know, it’s designed to avoid the confluence of disgust and desire and voluptuousness that are all wrapped up in this bizarre construct of racism. You know, what black stands for in white America and what white stands for in white America are all loaded with our deepest psychological perversions and fears and longings. And it’s a dangerous way of doing things, but it’s just human, weirdly human.

Kara Walker installs Gone, An Historical of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994) at the Tang Museum, Saratoga Springs, NY, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Can you talk more about the fodder of Gone with the Wind? You described the storytelling as soft porn and other stuff that was very offensive.

WALKER: What can I say? Within the story of Gone with the Wind—the actual novel and then the permutations of it in film and in life—my expectation, as I said, was to go in and be sort of horrified and disgusted with representations of happy slaves or ignorant slaves. The mammy figure is both soothsayer and does everything to please her white folks. And I went into my reading of the book with a clear eye towards inserting myself in the text, somehow. And the distressing part was always being caught up in the voice of the heroine, Scarlett O’Hara.

Now, I guess a lot of what I was wanting to do in my work, and what I have been doing, has been about the unexpected. You know, that unexpected situation of kind of wanting to be the heroine and yet wanting to kill the heroine, at the same time. And that kind of dilemma, that push and pull, is sort of the basis, the underlying turbulence that I bring to each of the pieces that I make, including the specifics: the mammy characters and the pickaninies and the weird sorts of descriptions.

At one point, Scarlett, in her desperation, is digging up dried-up roots and tubers down by the slaves’ quarters, and she’s overcome by a “niggery” scent and vomits. (LAUGHS) And it’s scenes like that—that might go washed over by the sort of vast, epic structure of the story—but that is an epic moment for me. What does that mean? And why is there an assumption that I should know what that means? And where does this idea come from, you know: why is this smell so overpowering?

ART21: So, the task is to question the underlying structure of racist thinking in an epic as quintessential as Gone with the Wind?

WALKER: Well, people will try and question it. Let’s say it gets questioned . . . But more poetic gestures happen in the real world, like the Margaret Mitchell house burning to the ground (LAUGHS)—by no fault of its own, I’m sure. I want to bring this conversation into the now—with, you know, Trent Lott or whomever, or just the idea that somebody like Strom Thurmond can be in office for an eternity and bring views from another era into the twenty-first century. But it gets ploughed under and ploughed under to such a degree that we assume, or the public assumes, that it’s not so important.

ART21: What’s not so important?

WALKER: It. The It: the “niggery” scent. The gross, brutal manhandling of one group of people, dominant with one kind of skin color and one kind of perception of themselves, versus another group of people with a different kind of skin color and a different social standing. And the assumption would be that, well, times changed and we’ve moved on. But this is the underlying mythology, I think, of the American project. The history of America is built on this inequality, this foundation of a racial inequality and a social inequality. And we buy into it. I mean, whiteness is just as artificial a construct as blackness is.

Kara Walker installs Gone, An Historical of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994) at the Tang Museum, Saratoga Springs, NY, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Who is the Negress in the title of Gone, An Historical Romance…? Is she your invention?

WALKER: Well, the Negress, as a term that I apply to myself, is a real and artificial construct. Everything I’m doing is trying to skirt the line between fiction and reality. And for the most part, I’ve titled exhibitions and a book or two as though they were the creations of a “Negress of Noteworthy Talent” or a “Negress of Some Notoriety.” I guess it comes from a feeling of being a black woman, an African American artist—that in itself is a title with a certain set of expectations that come with it from living in a culture that’s, maybe, not accustomed to a great majority of African American women artists. It’s like a thing in itself. And it’s a construct that is not any different to me than the Negress.

The Negress that I initially was referring to was out of Thomas Dixon, Jr.’s The Clansman. This is the great racist epic of the late nineteenth century, that Birth of a Nation was based on. And there’s a figure in there, who’s described as a tawny negress who is part secretary, part lover—this nefarious, dark vixen. She’s manipulating this misguided white statesman, who wants to put blacks in higher offices and change the culture—and with this tawny negress, with this vixen, be the arbiter of our social norms. Could this icon of all that is wrong and sexual and vulgar be uplifted to the highest? My answer being: Yes, she would, she will.

ART21: So, there’s a melodramatic aspect not only to the form that the work takes, but also to life as it’s lived now?

WALKER: Melodrama . . . I’ve always been interested in the melodramatic, in outrageous gestures. One thing that got me interested in working this way, with the silhouettes but then working on a large scale, had to do with two longings. One was to make a history painting in the grand tradition. I love history paintings. I didn’t realize I loved them for a long time. I thought that they were ridiculous, in their pompous gesture.

But the more I started to examine my own relationship with history—my own attempts to position myself in my historical moment—the more love I had for this artistic, painterly conceit, which is: to make a painting a stage and to think of your characters, your portraits or whomever, as characters on that stage. And to give them this moment, to freeze-frame a moment that is full of pain and blood and guts and drama and glory. It just became all the more relevant to my project.

And my project, it’s been about many things. But I think—and I sometimes forget to mention this—but the second longing is about trying to examine what it is to be an African American woman artist. So, it’s not just an examination of race relations in America today. I mean, that’s a part of it; it’s a part of being an African American woman artist. It’s about: “How do you make representations of your world, given what you’ve been given?”

Kara Walker installs Gone, An Historical of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994) at the Tang Museum, Saratoga Springs, NY, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Can you talk about the humor in your work? Is it a tragic humor?

WALKER: Giddy humor, giddy. I think I described this kind of turbulence that drives most of the work, and it’s a turbulence that’s not unlike melodrama, or the kind of dredging up of every feeling one could possibly have about a situation that is all about feeling. And it’s difficult not to laugh off that behavior—that sense of being overloaded, out of control, unable to contain even the horror of being able to think about something that you know you shouldn’t be thinking about, or that you know isn’t going to resolve itself just by thinking about it. It might not resolve itself by talking about it. It might not resolve itself by enacting laws about it. Or writing about it.

And it’s that feeling of needing to make this offering as a form of truth telling, no matter how awful it is, and then—ugh, you know—being flabbergasted at even having to do that! Why should that even have to be done? And then, sometimes the work is just ridiculous and silly and weird.

ART21: That sort of truth telling must be exhausting! Do you ever question yourself: “Why me?”

WALKER: I never say, “Why me?” I gave myself this job. (LAUGHS)

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.