Interview

“Proposition Player”

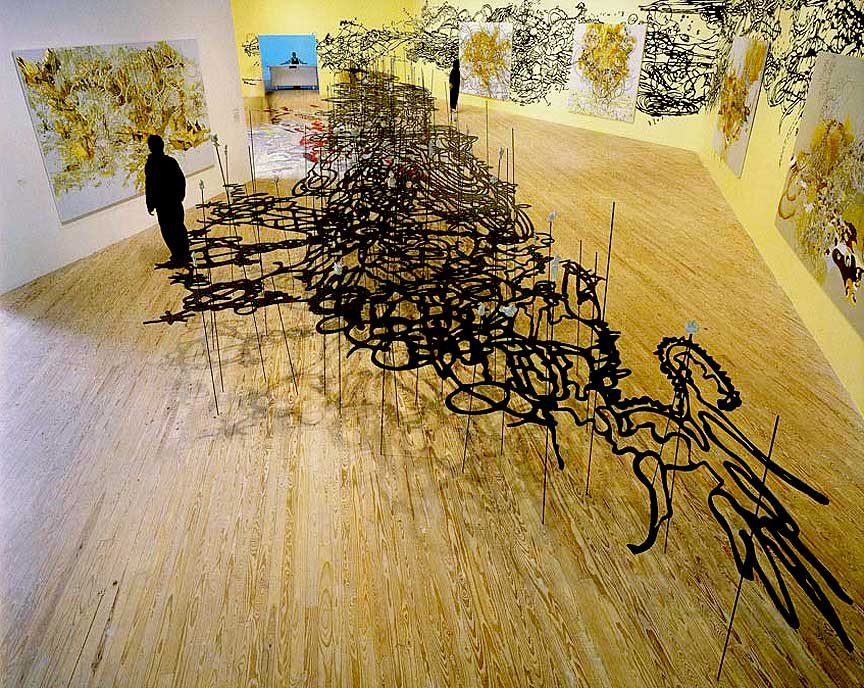

Matthew Ritchie. Proposition Player, 2003. Installation view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Texas Photo by Hester + Hardaway. © Matthew Ritchie. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

Matthew Ritchie discusses his work’s relation to scientific processes, as well as the participatory nature of his 2003 project Proposition Player.

ART21: What sorts of science journals do you read?

RITCHIE: I read Nature, this weekly journal of science. It’s so technical, just published raw data. You can glean enough of it to understand that there’s a huge gap between what people understand is going on in contemporary science and what is really going on. Like, the gap between the actual frontier of research and how it’s then filtered back to everybody else—it’s vast. Sadly, out of that comes ignorance and fear because the explanations are less informative and persuasive than the original experiments, which are much less conclusive and didactic.

Some people who are trying to put a popular spin on science end up simplifying it into either the Frankenstein argument (“It’s going to be bad for you”) or the utopian argument (“It’s going to be amazing, and there’ll be a flying car and a robot in your kitchen”). So, you get these two poles, neither of which are remotely true.

In fact, it’s just science—figuring out, question by question by question, what’s really going on. When you go back to the original material, you get what it’s really about: human beings just doing work, trying to figure stuff out. There’s no point of view; there’s no agenda. And that’s what’s amazing. You go back into history, and that’s the common thread that links every kind of investigation, whether it’s aesthetic or scientific or theological. Everybody’s just trying to figure it out.

ART21: Talk about a scientific versus artistic process.

RITCHIE: You’re really not supposed to talk about this. One of the curators at the Museum of Modern Art said the three big no-no’s were sex, science, and spirituality. So, I really have to go off the record to talk about any of them. These are the big three questions of our existence as human beings. My work is at least as much about science as it is about the other two, but science is an easier handle for some people to grasp.

In the contemporary climate, we’re all very wary—and I think rightfully so—about spiritual investigations. It’s all become this sort of corrupt miasma of claim and counterclaim, evangelical versus neo-Buddhist. Again, one of these absurd polarities has developed. Science has become the battleground for society to discuss its spiritual questions. It’s no accident that the real theological debate is about stem-cell research. It’s a scientific discussion; it really has nothing to do with a theological point of view. But because people can’t articulate their theological disagreements in any meaningful way, they’ve sort of hopped onto science.

The premise of science is that it represents order. By its nature, it therefore excludes an essentially theological interpretation of the universe. To come up with a theological counterpart as heavyweight as science, you would have to come up with a science of theology that was based on an ordered understanding of the theological relationships of the universe—which some people have actually tried to do in the past. It’s even more abstract, specific, and meticulous than science itself. It reverts back to the utopian versus the Frankenstein, again. This kind of balance kind of pops up because these are the great archetypes: Will it be good for us? Will it be bad for us? That’s what we want to know, so we cook it all down to these essential arguments. But I’m more interested in science as a way of having a conversation that’s based on an idea of looking at things than I am in the rhetoric around science.

My installations—they don’t [look] like laboratories. Other artists are interested in claiming the territory and the appearance of the laboratory, but the appearance of science has nothing really to do with what it actually is. If you look at a physicist’s journal, it’s just a bunch of scribbled marks because they’re doing work. They’re not particularly interested in large chrome tabletops; that’s just a byproduct.

Matthew Ritchie. Proposition Player, 2003. Installation view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Texas. Photo by Hester + Hardaway. © Matthew Ritchie. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

ART21: How does that tie in with your work?

RITCHIE: I’ve been working for a long time on this series of linked projects that deals with a group of properties, forty-nine properties or characteristics. Each of the properties or characteristics represents a function of the universe. Proposition Player at MASS MoCA was a gathering of a large group of those characteristics, fusing them into one project. But it left some of them out, and the ones that got left out were in The Lytic Circus at the São Paulo Bienal. Proposition Player is all about gambling and quantum mechanics, the elements of chance and risk, and how those things build into an entire continuum of meaning. The Lytic Circus is about what happens to the unacceptable elements of risk, the ones that you want to exclude to keep the bad out.

ART21: How do the two projects relate to one another?

RITCHIE: The slogan of Proposition Player was “You may already be a winner!” It’s about the idea that, in the moment between placing your bet and the result of the bet, there is a kind of infinite freedom because all the possibilities are there. “You may already be a winner!” It’s fantastic—you’re like a god! Everything opens up. The Lytic Circus is really about the opposite—a kind of prison of life where no risk is ever really rewarded. You’re trapped in a set of circumstances that are biological, temporal, physical, mental—locked in to a point of view. It’s about the idea that you may already be a loser—just as true as the statement that you may already be a winner. So, the illusion of risk, of gambling, is all that you have. But in fact, it’s just a circus. So, Proposition Player and The Lytic Circus are like counterbalances—the utopian versus the dystopian—it’s always sunny, or it’s always raining. In fact, you know most likely every day’s going to have a little bit of both.

ART21: Explain how the playing cards function in Proposition Player.

RITCHIE: When you go into Proposition Player, you are given a card by one of the guards. The idea of that is twofold. One is to make it a tangible gesture from me to the person visiting the show: Here’s a piece of the show for you; you get to take it home. And the other gesture that it’s making is: This is not strange to you; this is not foreign; you know what a playing card is; it’s a tool for playing a game.

The title of the show says it all. Proposition Player—you’re being propositioned, you’re being asked to engage in this game that has a very limited downside. The technology of the playing card is such a beautiful thing. It’s been around for a long, long time. No one mistakes it for some kind of art-related activity—it’s a playing card. You know you can throw it away. You can stick it in your pocket. Or you can go buy that whole pack of cards at the gift shop and play. It’s perfectly useable as a deck of cards; it has all the traditional suits.

But it’s also a key to the characteristics that I mentioned earlier. I’ve been working for years with these forty-nine characteristics, and I was thinking about this show and how I wanted to do a pack of cards because it was a way in. It takes the idea of a fixed set of relationships, which I’ve worked with for a long time, and turns it into something that’s completely shuffle-able. You can mix it up. There is no story in a pack of cards, but you can tell any story you want to tell.

The most important cards are the four aces; they represent the four fundamental forces in the universe: weak force, strong force, gravity, and light. There are only four forces in the universe, conveniently enough for me. They underlie everything, tie everything together. So, in this room, everything in my show, everything in your life, everything is held together by the four forces. And the four aces generate the four units of measurement, which are, progressively: time, mass, length, and temperature.

To make it into a proper pack of cards, of course I had to introduce a joker, which is time—absolute time rather than linear time, which is the totality of time. The kind of known time that we all live inside, that we measure off as the hours and the minutes in the days. And then there’s all of time. Then there are these characters called the gamblers, who start off with the four kings and proceed into all of the face cards. And they represent the quantum forces that devolve from the four aces. So, you have the Planck limit; you have photons coming out of light. You’ve got black holes coming out of gravity. And you’ve got duality coming out of the weak force. So, these three sets set the route. The rest of the pack builds out from that—moves through the forces and the structures of thermodynamics, chemistry, the periodic table.

So, you’ve got a card, you take it in, you give it to a guard, and he’ll let you play the game of chance—the dice game—which is also called Proposition Player. The game builds up into all of the elements in the paintings, which take you through this narrative that describes the evolution of the entire universe. You’ve started out as the smallest element, and gradually you see how essential that particle is to everything else. This is literally a little way of representing you in a giant game—you know, “Come in. Put your card on the table and play.” It’s really just taking the traditional aspect of confronting large complex ideas about the universe—which is one of awe—and inverting it to one of play. You already own this: your body is already filled and saturated with every single thing going on in the universe, so you may as well enjoy it. You don’t need to live in fear and shame about your relationship to this larger structure. It should be about joyous participation!

Matthew Ritchie. The Lytic Circus, 2004. Mixed media installation, dimensions vary with installation. Installation view: “São Paolo Biennial XXVI”, São Paolo, Brazil. Photo © Matthew Ritchie. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

ART21: How do people participate in art today?

RITCHIE: I’ve never understood any of the debates about modern art as some sort of form of alienated practice. Modern art is a gift; take it or leave it. Nobody’s forcing it down your throat. But once you’re there at the museum, you may as well relax and have a good time. All anyone is trying to do is try out some new ideas, something different. And I think there’s something enormously ambitious about that idea, that we are all trying to advance or at least question what’s going on. I just think that’s great. It’s really cool, the idea of a total freedom that it gives, like you’re not bound by any particular loyalty or reverence; you can just move forward in any direction you want. It seems like a gift. It’s certainly a gift to me, as a practitioner.

ART21: In a way, aren’t you inventing the universe in your work?

RITCHIE: I look at it more like this: There’s the real universe. We know through our scientific practices, or we have estimated, that we can perceive about 5 percent of the real universe. So, that’s 95 percent, gone. Dark matter, dark energy—it’s a very strange and complicated place. On any given day, you or I might be able to find out about 5 percent in our entire lifetime of all human knowledge. Now, can we use that knowledge all the time? No, it would be amazing, but we can’t. We can probably use, oh, 5 percent of that in our lives. And then, when it comes down to it, you probably make a decision based on about 5 percent of the 5 percent of the 5 percent of the 5 percent of the universe. And you’re pretty confident that that decision is a really good decision. You say, “That’s what I’m going to do today with my life,” or in this relationship, or with this financial decision. And you’re basing that on 0.00625 percent of the universe. And you’re totally confident that you’re somehow connected, because you are: you are connected to that, 100 percent.

I’m interested in reconstructing that chain of evidence that leads you from the one thing to the other, because there’s the real universe, then there’s what we see, which is really just a metaphor. It’s already a metaphor for the real universe. We can’t see 100 percent; we see 5 percent. Then we represent that as another little, diminished 5 percent to ourselves, and then we put ourselves in that 5 percent. So, we’re already playing the game that I’m playing every day. This is, in a way, sort of building back out and saying, “Okay, I’ve got this much, but I just kind of want to see just a little bit more, maybe 5 percent more.” And that’ll push me out to the next level of possibilities and kind of open it up.