Interview

Meaning and Influences

Laylah Ali. Untitled, 2000. Gouache on paper; 13 x 21 inches. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Artist Laylah Ali discusses her life’s relationship to her work and how she creates the characters in her paintings.

Art21: Do you feel that your work relates directly to your life?

Ali: On some level you make things because you have to. There’s a kind of electrical energy in you that means you have to do this thing. I think that a lot of my creative output has to do with that. I have to have a place to put whatever electrical or chemical loose ends I have. I do what I have to do.

If I’m going to be making things, I can be locked in a room, away from everybody. My way of participating in the discourses that go on in the world is to engage in here. So, I am still hooked in. I am very aware of what’s happening, or try to be, as much as I can. I think, ask questions, or make commentary about stories that I understand to be happening in the world. So, there are fragments of those larger narratives that make their way into the work. At other times, I will deliberately be ruminating on certain issues that I want to give a place to in the pictures.

In terms of my personal life, many things are in here. I often look at the paintings, especially some of the earlier work, and recognize things from my childhood or things that I’ve witnessed or experienced. I don’t usually talk about those things because I feel like it’s personal—it goes in there, it stays in there, it informs the work. And it deepens it. The things that are from me and my history work together with the larger narratives. Hopefully they gain more power that way, by having a personal resonance as well as one that’s focused outward.

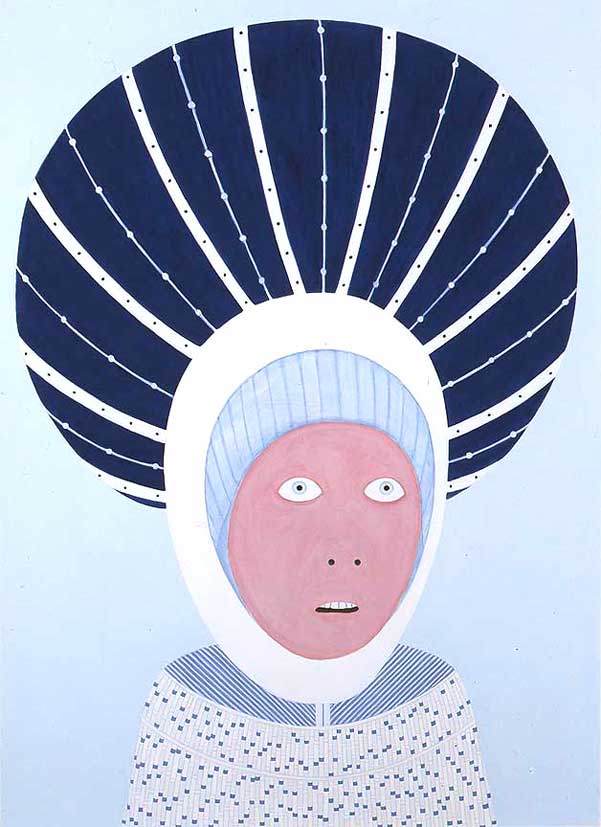

Laylah Ali. Untitled, 2004. Gouache on paper; 28 3/8 × 20 5/16 inches. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Art21: How do you describe what your work is about?

Ali: I’m not good with saying, “Well, this is what the work is about.” Work is about, “This is what happened to me” and “This is what I’m looking at in the world.” And it shifts. I’m working on this right now, and I couldn’t honestly tell you what this painting is about. It would take for me to finish it, look at it, live with it—and then I could maybe start telling you about it. But as I’m working on it, it’s still too close.

I’ve had time to look at my process for a while. I know that there are things in here that are very much connected to me and the time I’m living in, but I just can’t say, “Well, this is about the IRA and this is about South Africa” and “Oh, that wound there, that’s what happened to me when I was twelve.” That might all be true, but that’s not how I lay down the images. It’s almost as if that information comes in, goes through me, and comes out. And I don’t mean to make this mysterious or like I’m being guided by some external force, but there’s something that happens that I am not entirely in control of.

When it comes to looking at images of the sort of violence that’s happening in Iraq now—the soldiers over people lying on the ground with the guns to their heads—it’s not the first time that’s ever happened in the history of the world. But I live in this time and I look at those pictures and it has an effect on me. It makes me feel not just horrified or helpless or angry or like I don’t understand why this has to happen. It also makes me want to do something. And unfortunately in this America that we live in today—and maybe I’m wrong about this—even if people go out, march, protest, and make their opinions known or even if they vote in the majority against a candidate, it’s not working so that voices can be heard and things are changed. So, in some ways, maybe many of us are taking out our existential frustrations in places like this. That’s part of it. But then again, that’s not the whole thing either: these aren’t just political protest pieces.

When I was a student, I was always irritated at artists who wouldn’t answer questions about their work. There’s a kind of coyness that many artists have because they want their work to hold all meaning, because it makes it more important or exalted. So, you’ll be at an artist’s talk and they will go, “Well, I can’t really answer that. Oh, well . . . what do you think?” Always putting it back onto the viewer. And I don’t want to be coy in that way about the meaning of the work, because I certainly do put things in the work, and I do think about things. But for me to sit down and tell you everything about my life would be to answer the question about what the work is. I think that’s why it’s a hard question to answer.

Art21: Do you read a lot?

Ali: I read. I listen to a lot of radio: NPR or BBC. There’s a kind of repetition cycle of news on the radio, which is also of interest. The BBC repeats its stories very often and there’s just something about hearing the same horrific story eight times. You start to enter into the story or shut it off in different ways. So, that’s part of the information gathering, but also it’s a frustration at not getting information. For all the information that I hear, I still don’t feel informed. I mean, that’s a common complaint about our world today.

Art21: Talk about the importance of color in creating your characters.

Ali: Well, the old ones, the Greenhead figures, all had the same color head and same color skin. It was a kind of brown skin, a little bit darker than mine. They were always the same in that way. They had very different kinds of dress and masks and sometimes they had scalps or headdresses and things.

These new characters have a wider range of facial coloring. I hesitate to call it race because sometimes I think of them as having a skin condition rather than a race. Like, when your skin gets burned, it turns a different color or has a different texture—somewhere between race and a skin condition. Whether they’re even human is still a question to me. I make these portraits or characters, and they can be unto themselves—have their own realm, their own features. Or they’re hybrids—a mix between all my characters.

I’m still thinking about what it means. I’m fascinated—how a different facial color directs you. Green absorbs you into it. Pink or red comes out at you. Light pink doesn’t recede into the page but has a flatness. Bright pink jumps out. Those phenomena affect your reading of the figure—nothing related to anything but what a color does, how it affects your eyeball. I sometimes wonder if that is what it is about? Dark-skinned people: their faces absorb more light so you have to look at them more. They’re more mysterious? What is that? Could racism just be attributed to bizarre visual phenomena? There’s a question…

Laylah Ali. Untitled, 2004. Gouache on paper; 15 7/16 × 15 2/16 inches. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Art21: How did you begin to create these characters?

Ali: It started with figures I made in ’96. I put this big green head on this brown superhero body—but not really a superhero because it was an emaciated, silly, almost child’s body that didn’t look like our conception of a superhero. It had on Underoos, or something between a 1940s bathing suit and superhero gear. I looked at it and thought, “What am I looking at? What have I done? What does this mean?” The figure was like a question mark. I would look at it, and I had no idea what it was. That prompted further examination. As I worked further, I wanted to see more. Eventually they were put in blue backgrounds with a white floor—very simple setting, but it set them apart. From there, things have remained relatively simple and focused but a bit more complicated than the earlier ones.

Art21: Talk about the details you wanted in the Greenhead paintings; for example, dodgeballs and belts.

ALI: Dodgeballs—there’s a misconception. Many people thought my dodgeballs were basketballs. And actually they look nothing like basketballs. I think that had to do with the brown skin and the tall figures. That threw certain individuals into basketball, but they were dodgeballs made from that chalky maroon dodgeball color. I’ve always been fascinated by dodgeball. I just read in the paper the other day that there was somebody trying to get rid of dodgeball. Finally! I mean, I don’t know how long it’s going to take to wake up to the fact that this is a cruel game where the weakest get targeted. There’s something from my childhood—that dodgeball. Being the only black child in a white elementary school, dodgeball was not enjoyable.

Belts—because of the multiple ways they can be used. Belts being practical, to hold up their pants, belts as instruments of domestic violence, belts to hang some of my characters. Superheroes most often have belts. If we’re going to use that word, power—belts connote some kind of power. Imagine policemen without belts. You couldn’t take them seriously.

Art21: Do you think your paintings function like pictograms?

Ali: Hieroglyphics feel closer, because of the visual nature. Sometimes I feel like I’m making an extended alphabet, or that images encapsulate parts of an idea. By using parts of that alphabet or hieroglyphic system, I can recombine them and come up with new meanings. Because they’re so crisp and have definite shape, sometimes I think it feels like they’re letters.