Interview

Characters, Myths, and Stories

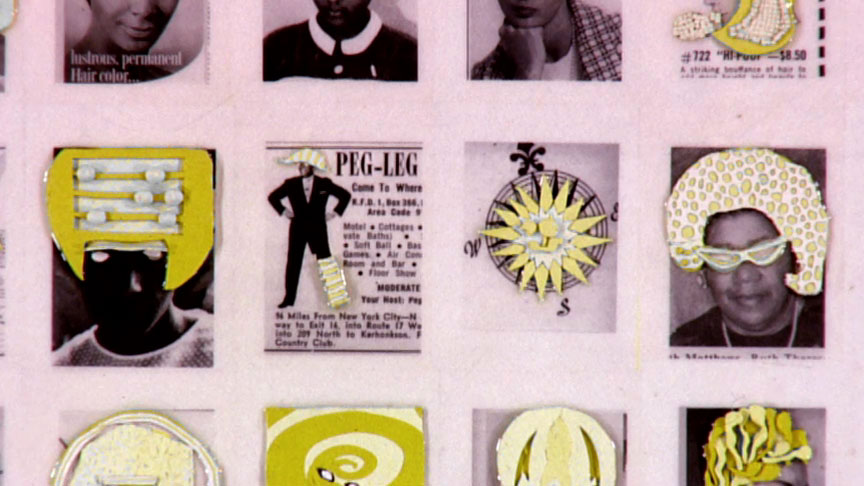

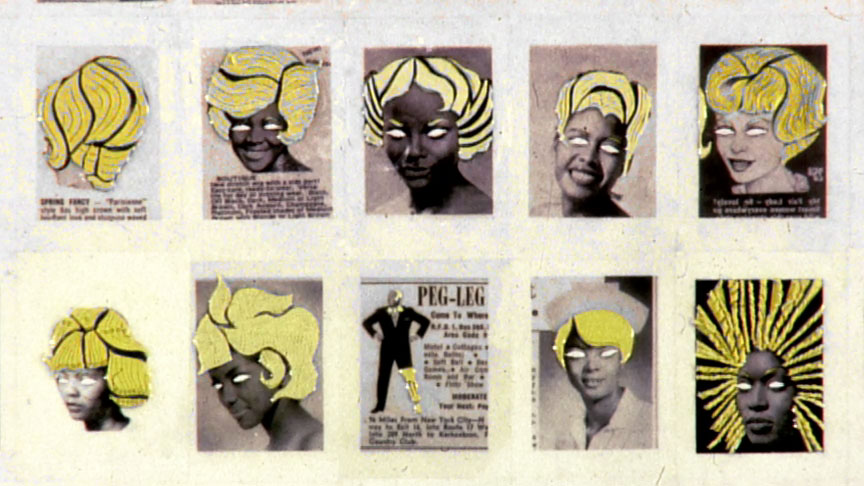

Ellen Gallagher. eXelento, detail, 2004. Installation view at Gagosian Gallery, New York, 2004. Plasticine, ink and paper on canvas; 96 x 192 inches. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, New York.

Artist Ellen Gallagher discusses the characters she employs in her work, such as Pegleg and Eunice Rivers. She also talks about how she moved from painting and collage to film.

ART21: The character of Pegleg is repeated in the paintings and prints. Why is he there?

GALLAGHER: He’s there for a kind of insistence. It’s hard to put it into language because it’s a form, but for me, Pegleg implies travel and worldliness. That ad appeals to me because of the way Pegleg Bates, the actual actor and comedian, used his whole body. It’s this man with this wooden leg offering himself as your host. The ad itself exists as a map to this hotel in upstate New York. I liked the idea of having a map within a map.

In Melville’s Moby Dick, you’re aware of Pegleg’s body and the sound he made as he moved across the deck. I like the way you’re so aware of people’s physical presences—Queequeg’s tattoos, Pip dancing, the way that Ahab moves. I want to make a texture felt in the paintings.

ART21: What about the nurse character—who is she?

GALLAGHER: Eunice Rivers, the nurse, that’s such a specific character. The nurse could refer to Julia the nurse and the sort of idealized professional woman of the ’60s. That’s Diane Carroll as Julia, and to think of Julia as sort of doubling as Eunice Rivers just kind of cracks me up (in an unkind way, I suppose).

The nurse exists in the paintings and as an ad. They were these ads to serve your people and be professional and ambitious. Ahab and Eunice Rivers exist for me as a sign for travel and hunger. Eunice Rivers was the nurse that ushered scores of black—mostly illiterate and poor—farmers through the Tuskegee experiment. This experiment began in 1939, and the story broke in the press in 1972 or ’71, and she was interviewed. She was indignant because she felt this was the first time any of these men had been through the health care system. Anytime these men had a cold or a flu or needed to see a doctor, that was made available to them because they had been part of the Tuskegee experiment. At the same time, they were subjects of a hideous experiment to study syphilis to the end of its natural course, and the experiment continued well after a cure was developed. These men were never offered the cure. Those that had it were observed to their death.

Ellen Gallagher. eXelento, detail, 2004. Installation view at Gagosian Gallery, New York, 2004. Plasticine, ink and paper on canvas; 96 × 192 inches. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, New York.

ART21: What is Drexciya, and how is it a metaphor for your work?

GALLAGHER: There’s this Detroit house band, Drexciya, that sees themselves as channeling oral hallucinations from the Middle Passage. They imagined this black Atlantis made up of women and children who went overboard during the Middle Passage. And it’s this kind militarized zone of this underwater sea world.

In much of my work, there is this idea of the gigantic, but in a miniaturized form. In terms of the subject matter, it can be something sort of awful that’s then reduced to a very minute observation, maybe a specific gesture or specific narrative. But it can also be in terms of the form, the way that the Watery Ecstatic drawings are made, which is much like my version of scrimshaw.

Scrimshaw was this carving into bone that sailors did as they were out whaling. I imagine them in this overwhelming, scary expanse and then having this kind of focus that would give you a sense of control, being in control of something—this kind of cutting as control. Scrimshaw basically had three genre forms: images of home, naked ladies, and images of whaling. So, much like scrimshaw, I’m cutting directly into the thick stock of watercolor paper, imagining this place, but my idea of home is more like this sort of constant return. The voyage itself becomes a kind of origin myth that I’m referring to. So for me, it’s the Middle Passage itself, rather than some version of an origin myth based on a Mother Africa. It’s the passage itself. It’s the concept of mutability that, I think, is the kind of origin myth that I’m referring to here, both in these drawings, literally, and more distantly in the paintings.

In 2001 I started making a sequence of films called Murmur, from the Watery Ecstatic drawings. The first film—also titled Watery Ecstatic—refers most literally to the drawings, in terms of the way the paper is cut and the drawing done over it. It’s this moment of being submerged; there’s a marine mountain and these heads bobbing up and down in the waves. It’s very crudely done. It’s real and mythological at the same time, this underwater black Atlantis—Drexciya.

The next film is Blizzard of White, which is Claymation, and it’s made with these tiny bits of Plasticine. Plasticine, which is also used in the paintings, is meant to suggest form and motion because it’s used in Claymation. And so, even when I use it and it’s still in the painting, it’s meant to suggest motion. It’s always meant to suggest mutability or change—that something will then move from one place to another or shift. In the film, lots of little bits of white Plasticine are formed into different sea creatures and descend again, down into Drexciya. And there’s this black volcanic back-drawing scratched in graphite and ink.

Ellen Gallagher and Edgar Cleijne. Murmur: Watery Ecstatic, Kabuki Death Dance, Blizzard of White, Super Boo, Monster, 2003. Five 16mm film projections; dimensions variable. Installation view at Gagosian Gallery, New York. Photo by Tom Powel. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, New York.

ART21: Why did you decide to make films?

GALLAGHER: The films do what I would hope people would do with the paintings in mind: go back to this idea of a collection of materials that has been opened up and spread out sequentially; activate your own sequence through it. The films are also a grid, where each frame erases the frame before as you move forward, so it’s literally a projection of a grid in space. But it’s the same place over and over again. And that is what I want you to do with the paintings. It’s about the idea of travel or motion—descent into an altered state.

For me, each repetition is about an inauguration of a character into an altered state—a way to change that character slightly or pull it further into difference and change, and into my language. I’m not the only artist who’s interested in repetition and revision. So many women artists before me have used that: Gertrude Stein, in her insistences, and Eva Hesse. And of course, it’s a central aspect of jazz.

What is happening in the paintings is that each time you see Pegleg (hopefully, you would always see at least two of these paintings together), you realize he’s there again. The paintings exist as a kind of picaresque novel in the way Melville’s beautiful collection of stories, The Confidence Man, does. It’s actually hard to understand what that form is; is it a novel? There’s this one character who is always in each chapter, if you can even call them chapters, and there’s a kind of scam that happens. You’re pulled into the confidence of this confidence man, and the question at the end of the book is, “Have there been several different characters doing several different confidences, everyone trying to fool you on board this steamship? Or is it this one character in several different guises?” I’m very attracted to that as a form.

Ellen Gallagher and Edgar Cleijne. Monster, from the suite of five 16mm films, Murmur, 2003. Photo by Tom Powel. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, New York.

ART21: Are you playing the role of the confidence man in your work?

GALLAGHER: I think so, yes.

ART21: What about the risk of being fooled?

GALLAGHER: There’s an ominous sign in the first chapter: it says “No Confidence Here,” meaning no credit. It’s such a pun. This giant steamship is traveling upriver, and all these characters exist on this steamship, and they’re all tricking each other. Or it’s one character tricking everybody on this boat. That risk of being fooled or conned is really important to me.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2005 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.