Interview

Influences

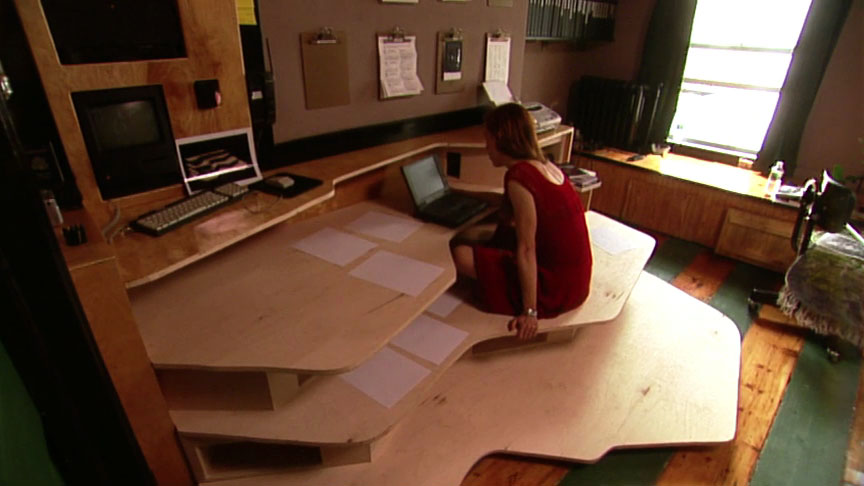

Production still from the Art21 Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Consumption, 2001. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

Andrea Zittel talks about her environment and the kinds of designs that influence her work.

ART21: Does where you live affect your work?

ZITTEL: I think that my work’s always been really influenced by the places that I’ve lived in. In fact, if you look at every body of work, you can trace it back to particular circumstances that I’ve had to deal with. For instance, I moved to New York in 1990, and the first place I lived in was this really tiny storefront in Brooklyn: it was—what—two hundred square feet? So, it had one hundred square feet in the front—a ten-foot by ten-foot room that I decided was my public space—and a ten-foot by ten-foot room in the back that was my personal space.

And at that time, I was doing really different work: I was working with animals and breeding them. But part of that was making these structures—these breeding units for them—that they would live in. I had sort of developed a particular aesthetic and technology for building these, with these welded steel structures, and then these wooden inserts that were pretty flexible. So, for instance, a breeding unit not only would influence the way that the animal would develop, but also it would have everything built into it that the animal would need for living.

So, after doing this work and living in this tiny space for a while, I think that it started to make perfect sense to try to create structures like that for myself to live in. When I first started doing furniture, or what later became the living units, I didn’t really consider it part of my artwork. It was simply a solution for these circumstances that I had to live in. At almost exactly the same time, I started thinking a lot about modern design, which is something that people always associate with my work. I think it’s funny because, in reality, I’m very drawn to antiques and older things. I think that I like things that have colors and are decorative. I could never really understand modern houses in my neighborhood, when I was growing up. I come from, like, a very lower-middle-class background, where that seemed just completely inaccessible to me.

But what became really interesting about that was modern design. For instance, before this period in art history or design history, value or what they represented to people was completely determined by how expensive the materials were that went into it—how much handcraft. These were these very physical, material codes. And what happened, then, was mass production, and the Industrial Revolution happened. And all of a sudden, it seemed like everyone would have the same goods. What really appealed to me about it was that, before, things like white walls, functionalism—things that could be mass-produced—all these things represented poverty. And all of a sudden, they were reinterpreted. It was like an ideological code that said: all these things that meant you were poor, all of a sudden became the moral elite. And I decided that, just by the nature of my existence, I didn’t have that many things. I had to move a lot. I couldn’t afford these sort of really, like, high-end materials.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Consumption. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: What’s interesting is that your work seems to embrace that sort of austerity, of not having a lot of things or expensive materials.

ZITTEL: Well, there’s a continual theme in my life and in my work. It’s about taking something that seems like it’s one way and flipping it over so it becomes the other. So, I like to take things that are, maybe, limitations in my life and try to somehow recontextualize them—glamorize them, make them more interesting—and vice versa. So, I took my simple living situation, and used this certain aesthetic code of modern design, and made it (in my mind) very glamorous. Since I couldn’t afford to live like everyone else, I wanted everyone else to wish that they could live like I did.

Like I said in the beginning, I didn’t really consider that to be my artwork. I had something else that I was doing as my work. But what happened is: so many issues kept coming up, and I felt like these were ideas that were complex and evolving. They were things that I felt like other people could identify with. I was using myself as a guinea pig, using myself to understand society at large. So, it became far more interesting for me to continue to follow that direction and to research that as my artwork.

ART21: Was there a certain moment that marked this turn for you?

ZITTEL: Well, I think that the most telling moment came when I started to do studio visits. People would come over to my studio, and we would sit in this living unit and discuss the work. I would say that three-quarters of the conversation would be based on this structure that we were sitting in. It was really interesting that, when people would come over, they would end up reflecting on their own desires and philosophies about the way that the world worked—and the way that they wanted their environments to be, and how environments would influence them, as well as how they would influence their environments.

ART21: How big was the first Living Unit? How was it put together?

ZITTEL: It was actually a welded-steel framework. I think the whole structure was about eight-feet long, and about five-feet wide, and seven-feet high. We actually welded this structure that almost looked like a Mondrian, this sort of very geometric painting, and then made these wooden inserts. The reason I did that was because things were continually shifting. I hadn’t quite figured out exactly how much space I needed for each function. So, with this, I could change the wooden parts that went in it. I could build cabinets in some places, and shelves in others, and shift those around until I had it just right.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Consumption. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: Do you see this sort of work as being influenced by growing up in Southern California?

ZITTEL: I think that so much of my work has been completely influenced by the culture that I grew up in. I grew up in very suburban Southern California. I think my parents had this fantasy about building a country home in the middle of nowhere. So, my dad built our home on the edge of a mountain. And then, by the time I was in high school, it was completely built up. It was suburbia. Our house looked exactly the same as everyone else’s. There was a shopping mall. The final coup was they put a shopping mall in on our street, which put our whole neighborhood on the map. My mother used to go jogging in T-shirts that said: “Stop the malling of the park.” I went to art school, and I was very embarrassed about coming from there. (And I tried to change my accent, which is very much Southern-California-mall-girl. It always shocks people, when they meet me.) I tried to make work that was serious, that was more international.

It was only after I moved to New York that I realized what a gift it was to come from some place so normal. I’m basically this specimen of what I think 95 percent of our population is. And it’s really important for me to bring all of those issues in to my work. People talk about my work, a lot, as having to do with these European modernist ideals. But in reality, what I’m interested in is how I grew up in this very generic, very capitalist culture—and how the values that are instilled in me relate to these very utopian thoughts at the beginning of the century. And how some of those ideas—some of the things that people wished for society—actually manifested themselves in that way, very twisted manifestations of that.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.